Revulsion and surveillance

Despite sympathy for the oppressive situation in tsarist Russia the political activities of the Russian revolutionaries and the young students in Switzerland was a constant source of resentment.

Looking back on this time, Robert Grimm reminisced as follows: “In Bern, the Russian students [...] lived in the Länggasse district. From the moment they moved in, public sympathy subsided noticeably. Dressed poorly, uprooted from entirely different circumstances and planted into lower middle-class Bern, intellectual and hungry for knowledge, lively and very politically minded, their habits did not fit in with the quiet lifestyle of Bern families.” While there were always plenty of landlords in the university towns willing to accommodate students in their guestrooms, others vociferously opposed the presence of too many “Slavs” and “Eastern European Jews”. The newspaper Anzeiger für die Stadt Bern constantly carried apartment ads which explicitly stated “No Russians”.

Robert Grimm around 1915. Photo: Wikimedia

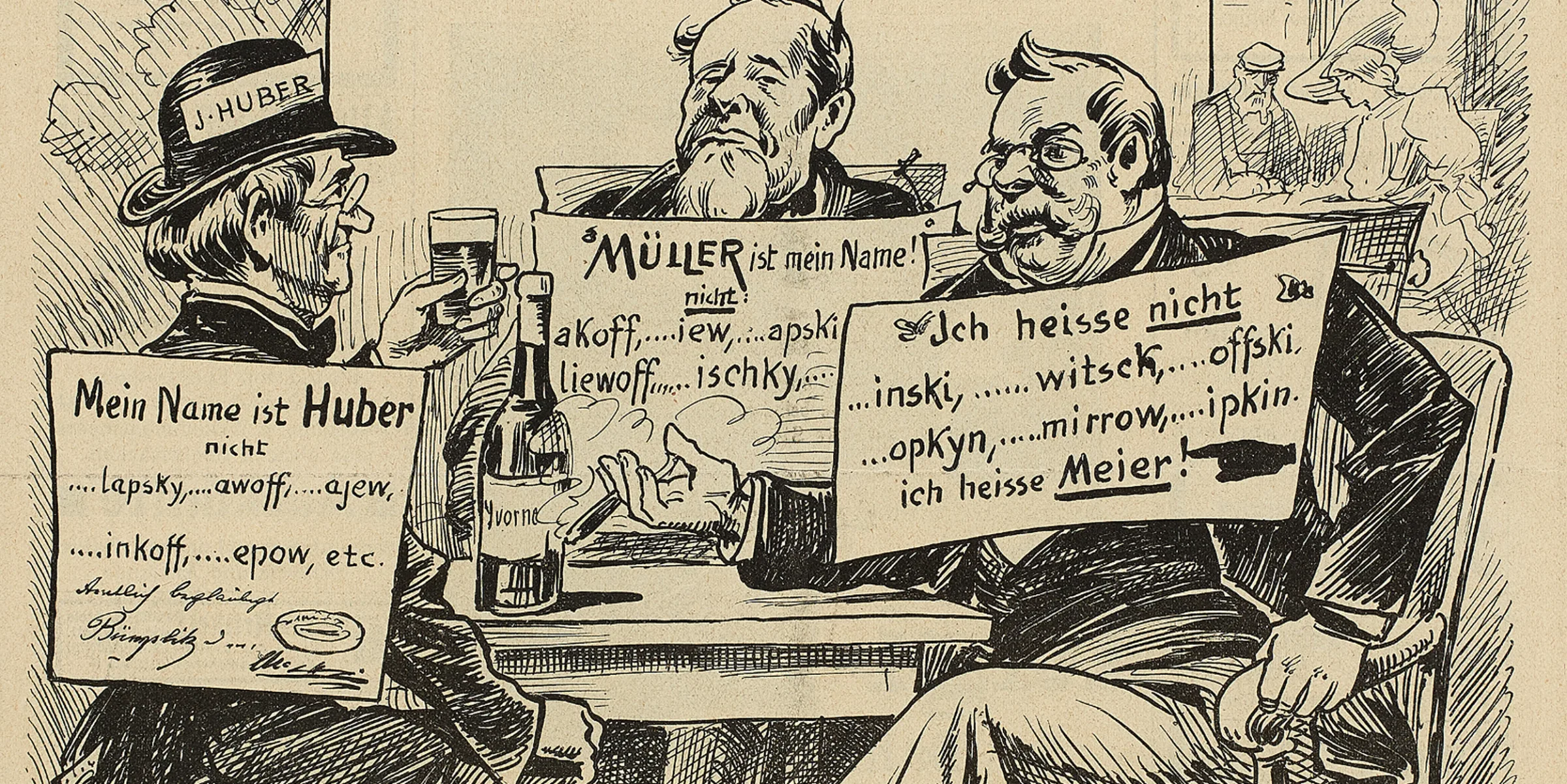

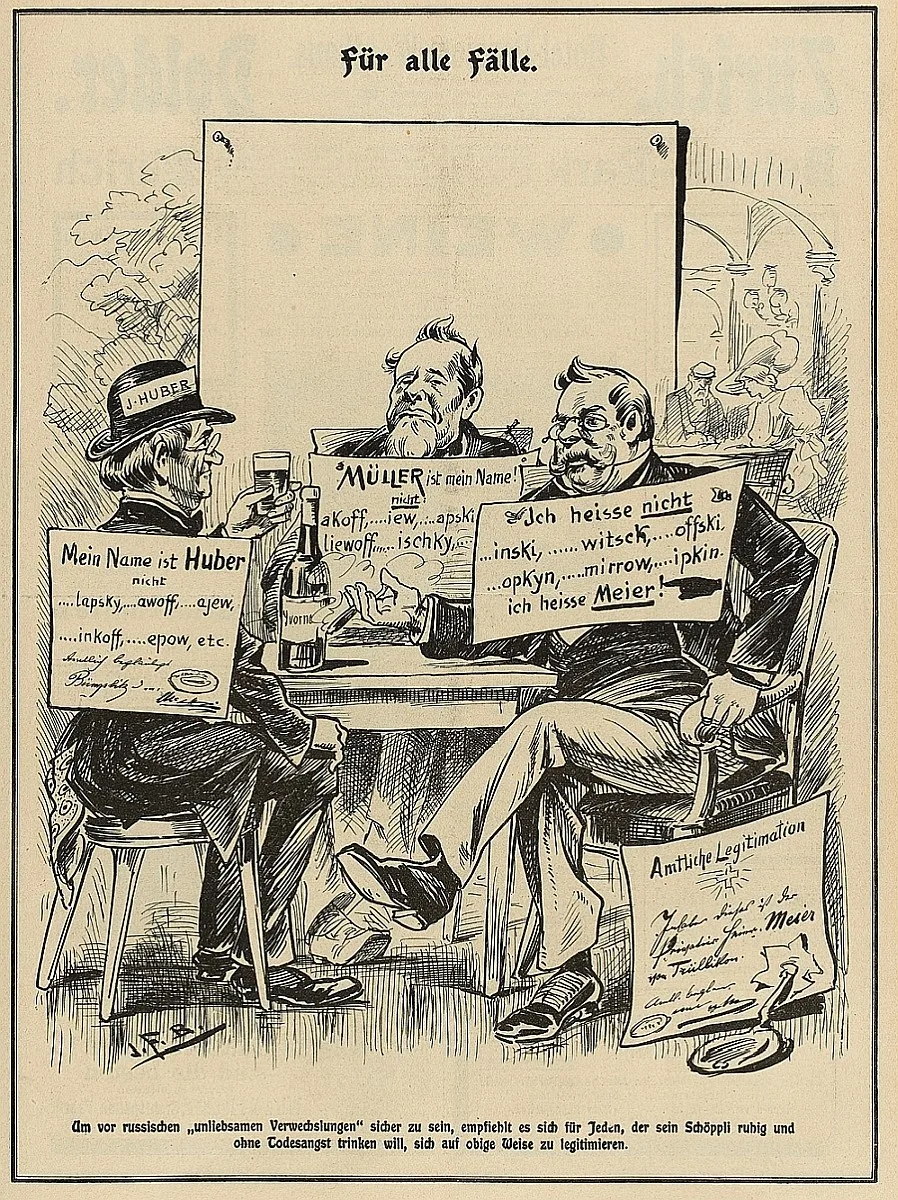

For some, this revulsion may have been caused in part by memories of the Russians who around this time had planned, or even carried out, assassination attempts against high tsarist officials , such as Tatyana Leontyeva, who killed an Alsatian retiree she had mistaken for the former Russian Interior Minister at Grand Hotel Jungfrau in Interlaken on 1 September 1906. The Swiss newspaper Nebelspalter published a caricature which related directly to the fatal mix-up and advised Swiss citizens to wear name tags or hang a board around their necks to certify that their names did not end with “-insky”, “-vich” or “-ofsky”.

The Russian authorities had long had their sights on the revolutionary emigrants, but after incidents such as this intensified their surveillance and attempt to infiltrate revolutionary circles with spies. The Swiss authorities too were anxious to keep abreast of the Russians’ activities: placing some of the revolutionary emigrants under very close surveillance, assigning experts to translate the exile press and analysing or intercepting telegrams. In a few cases, Swiss prosecutors even worked together with tsarist police authorities. When Angelica Balabanova, a well-known revolutionary and key pillar of the Zimmerwald movement, was expelled from the Canton of Waadt in 1906 for revolutionary agitation, the Swiss public prosecutor’s office had obtained information about her in advance from the Russian Interior Ministry.

Also the Swiss press adopted an increasingly hostile tone towards many Russians. For example, the Berner Volkszeitung newspaper wrote in December 1906 that the “complaints about the Russian plague” could no longer be ignored. The revolutionaries, for their part, responded to the increasing attention and surveillance with their familiar conspiratorial practices. They left behind as little written documentation as possible, published their newspapers under constantly changing names, used pseudonyms and post office boxes and maintained connections with allies in Russia through their own international network of couriers and informants. In her autobiographical writings, Cecilia Bobrovskaya includes an impressive description of how they had to learn long lists of secret passwords, code words and addresses by heart. “I shall never forget how we paced the room like a pair of school girls, earnestly memorizing [...]; password—‘We are the swallows of the coming spring.’ Or, [...] Password—‘I have been sent to you by the singing birds.’ Answer—‘You are welcome.’“

Caricature from the satirical newspaper “Nebelspalter”, Zurich, 8 September 1906. Artist unknown. Photo by Johann Friedrich Boscovits. Nebelspalter Verlag, Switzerland.

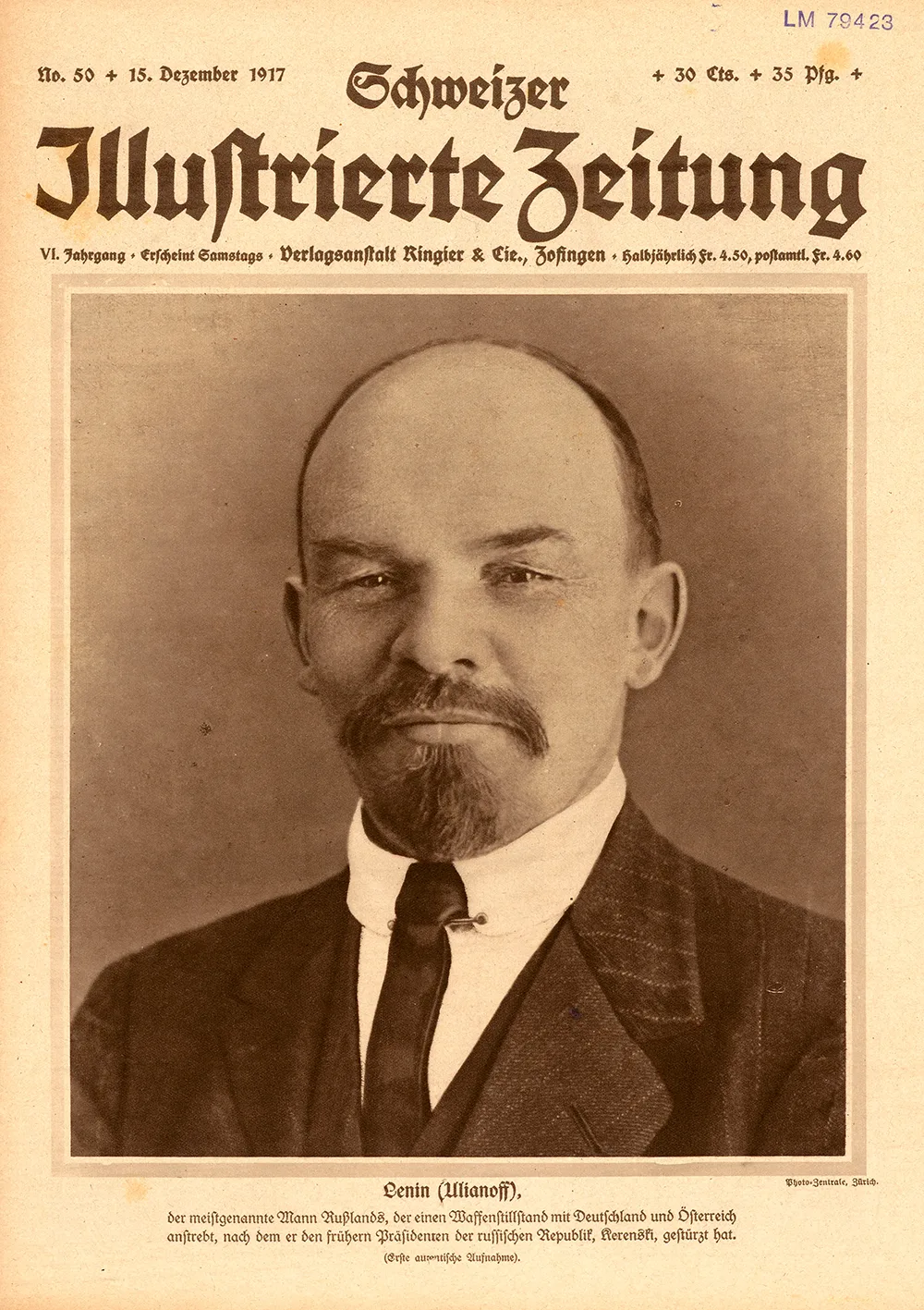

Schweizer Illustrierte Zeitung, no. 50, 15 Dec. 1917. Photo: Swiss National Museum