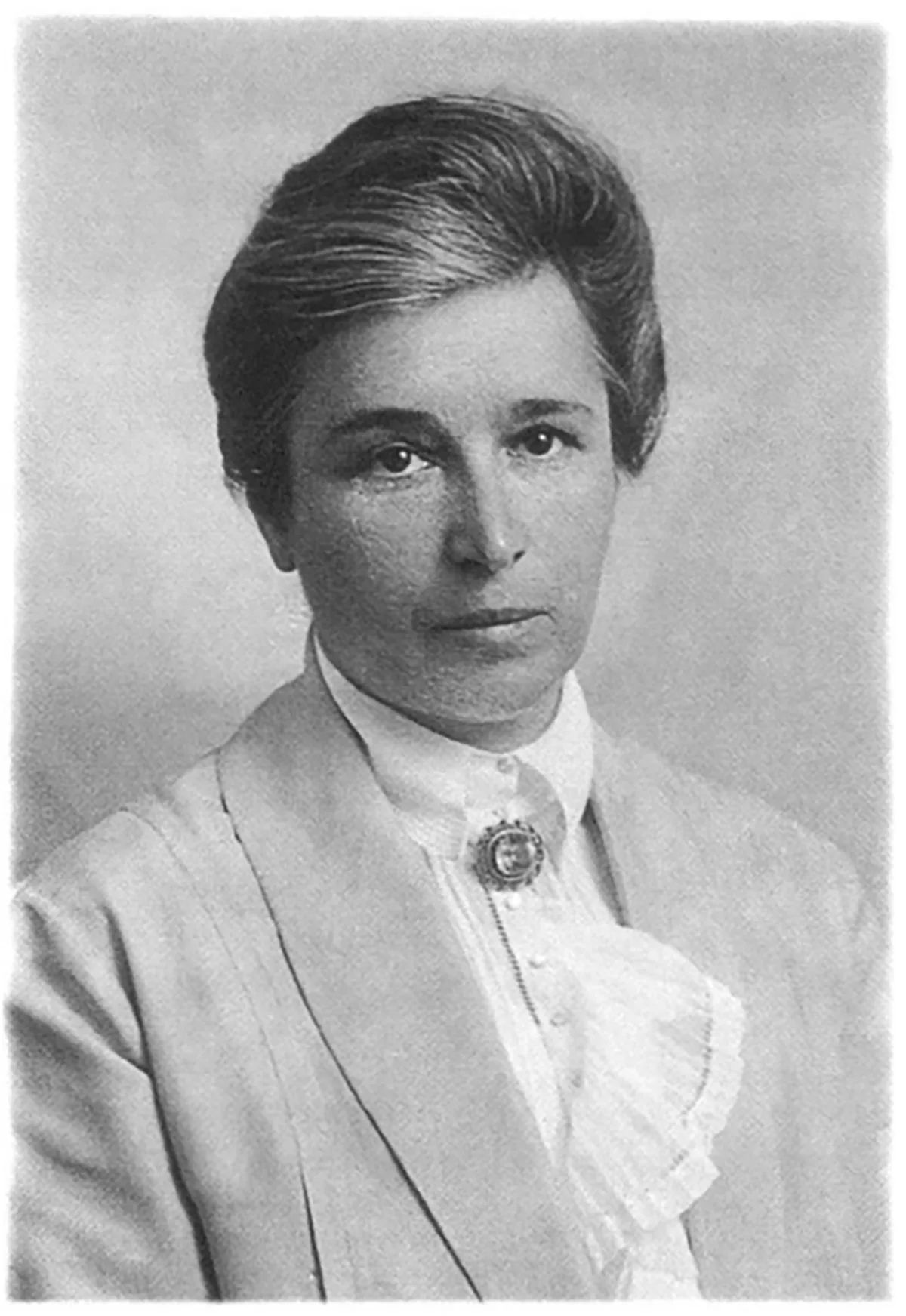

Physician Ida Hoff’s feminist interpretation of Hodler

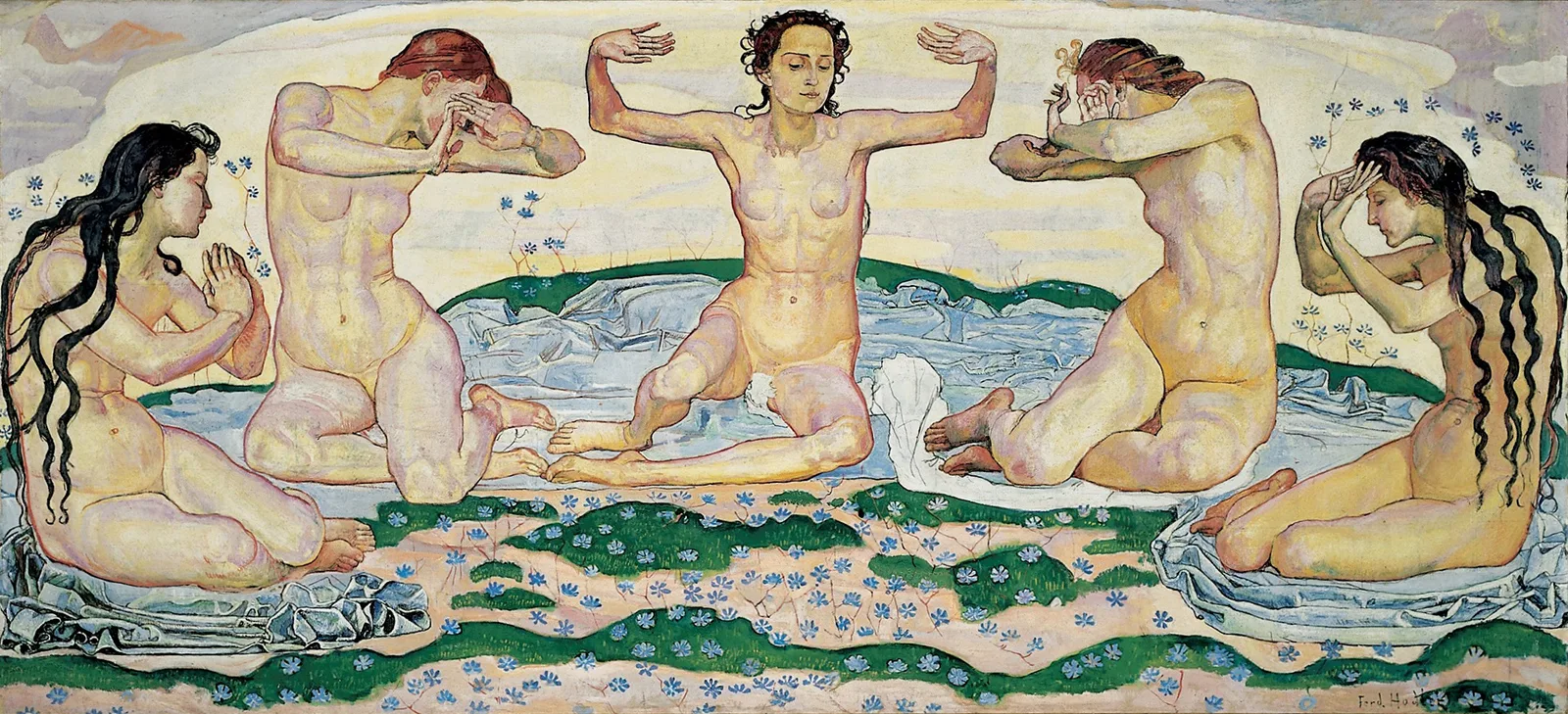

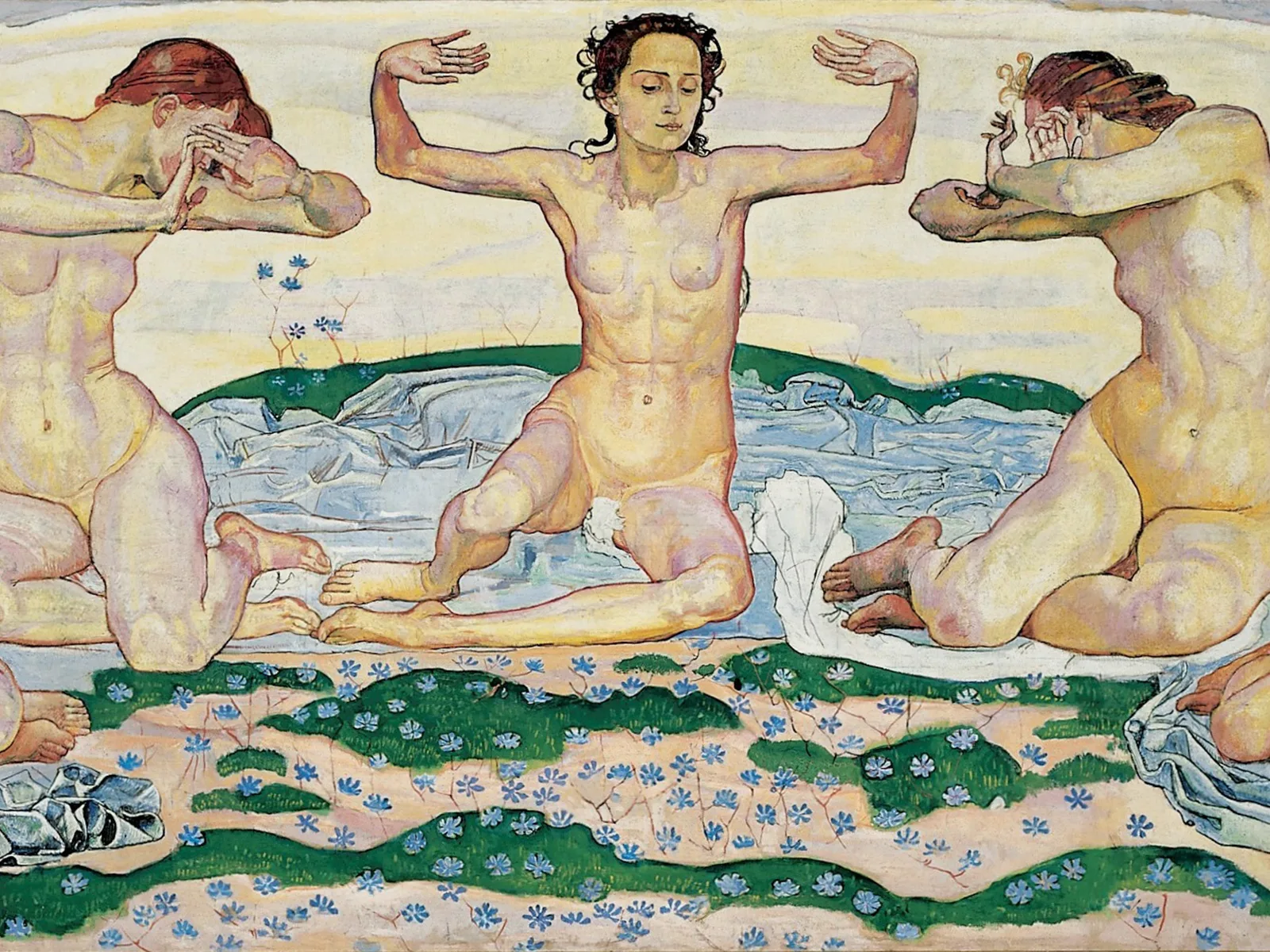

Born in Russia, Ida Hoff became one of the first women to attend university in Switzerland around 1900. In addition to pursuing a career in medicine, she was a staunch advocate of women’s rights, guided by her feminist conscience and a penchant for irreverence. She found an outlet for the latter at the second Swiss Congress for Women's Interests in 1921, where she wittily subjected Ferdinand Hodler’s painting “The Day” to a fresh new feminist interpretation.