Two Swiss villages on the Black Sea

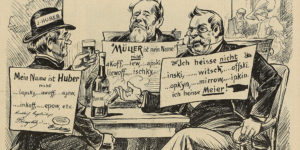

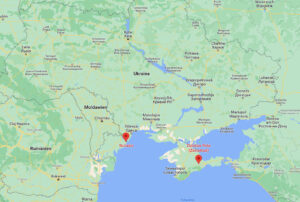

Ukrainians are fleeing westwards into the unknown, with some also heading to Switzerland. More than 200 years ago, Swiss settlers migrated east to Ukraine and established two Helvetic colonies: Zürichtal in Crimea. And Shabo near Odessa.

Emigrants from the Knonau district

The Swiss settlement flourishes

Zürichtal becomes Zolotoe Pole

Ukrainians in Switzerland

The Tsar’s Swiss winegrowers