Mystery of the St. Gallen Globe solved

The origins of the St. Gallen Globe have finally been revealed: it comes from northern Germany and was built by globemaker Tilemann Stella. These new discoveries have been made thanks to a piece of parchment bought from a junk shop.

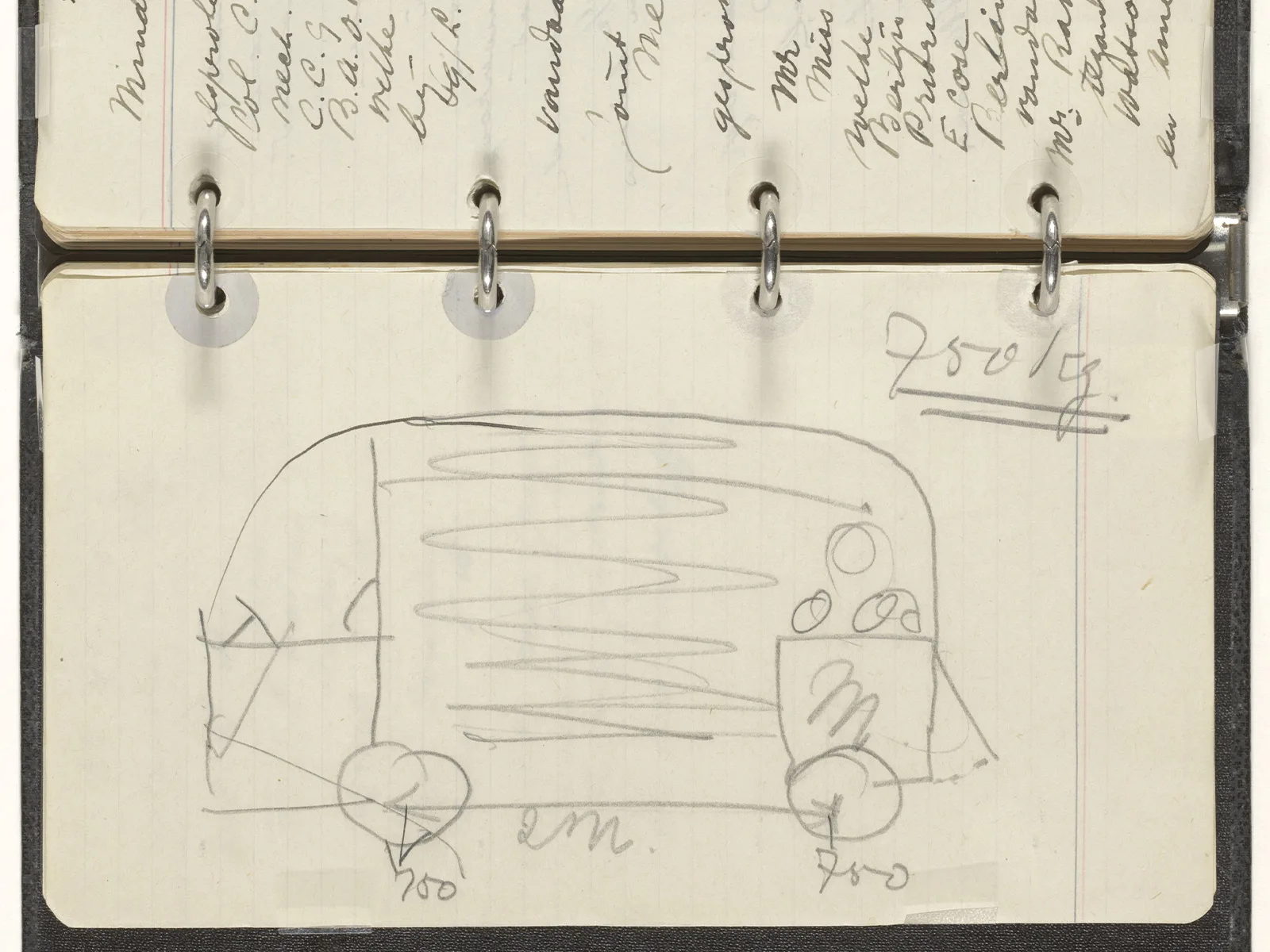

Were one to make a film, this would be the perfect script. Some years ago, a chef from the Swiss town of Olten buys an old drawing for a few francs from a junk shop and hangs it up on his wall. At some point, he finds himself thinking that this piece of parchment could be something more than just nice to look at. He asks a local historian, who swoons with excitement. It turns out that the drawing is extremely valuable and furnishes new clues on the origins of the St. Gallen Globe. One of the most important artefacts of Swiss cultural history, the globe has been housed in the National Museum Zurich for many years.

It was always thought that the St. Gallen Globe was made in either Augsburg or Konstanz. Now, however, the Olten chef and his drawing have provided some new leads to help solve this mystery and have prompted researchers at the Zentralbibliothek Zürich – Switzerland’s central library – to run optical and radiographic analyses on the artwork, which it has now acquired. These analyses revealed three overpainted portraits of historical figures hidden in the globe’s supporting arms, which allowed its origins to finally be explained. An evaluation of the findings has revealed that the globe was made in the late 16th century at the court of the Duke of Mecklenburg in Schwerin. Its builder was Tilemann Stella (1525–1589), who was in the service of the then duke, John Albert I. Nevertheless, the globe – which shows both the Earth and the stars in the night sky – had to be completed in two goes. By 1576, it was practically finished, barring a few decorative touches. Later that year, however, the duke died following a short illness, leaving the globe without an official dedication. His son John VII later had himself depicted in one of the overpainted portraits, proclaiming himself the globe’s patron and owner. After he then died, the court ran into financial difficulties and was forced to sell valuable property to pay off its debts. Thus it was that the globe found its way to the Abbey of Saint Gall in St. Gallen.

Unfortunately, it so happened that two of the portraits on the globe were of the scholars Gerhard Mercator and David Chytraeus, both fervent supporters of the Reformation – and, in other words, hardly people that the Prince-Abbot would want adorning his globe. He therefore ordered the two men’s portraits to be painted over and masked. While the Lutheran polymath Mercator disappeared completely under a new coat of paint, Chytraeus was transformed into the Greek scientist Archimedes. Clearly a mathematician and physicist from Greece was a better fit for the Abbey of Saint Gall than a reformer from northern Germany. Further clues, such as the similarly retouched portrait of Prince John VII, who was made into a monk, as well as names of local saints, the addition of the town of Rostock to the map, and the presence of the Julian calendar – which in the late 16th century only the Protestants used – point clearly to the court of Mecklenburg as being the globe’s first home.

So a major riddle in the globe’s history has now been solved. One question remains, however: where does the chef’s drawing fit into all of this? It was originally produced as a kind of sales brochure for the globe when the ducal family were looking to sell the prestigious work of art somewhere far from home. Clearly the court’s reputation would have suffered had such an eminent item simply gone to a buyer just down the road. A detailed sales brochure was therefore designed and sent to southern lands. How it ended up in the junk shop to be bought by the chef from Olten will probably never be fully explained. Unlike the latest discoveries about the St. Gallen Globe, however, neither does it necessarily ever have to be. So...

In conclusion, we can safely say that history is as thrilling as a crime novel and staff at the Zentralbibliothek sometimes do more detective work than actual research!

The complete scientific analysis of the St. Gallen Globe was published in the Zeitschrift für Schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte (Journal of Swiss Archaeology and Art History), Volume 74, Issue 2/2017. The journal can be ordered from the publisher, Karl Schwegler AG, Hagenholzstrasse 65, CH-8050 Zurich, or purchased from the shop at the National Museum Zurich.

The drawing found in the junk shop turned out to be a sales brochure for the globe. This illustration allowed the origins of the valuable artefact to finally be revealed. Photo: Zentralbibliothek Zürich

The St. Gallen Globe was made in northern Germany and later sold in eastern Switzerland. Photo: Swiss National Museum

David Chytraeus, a reformer from northern Germany, was transformed into the Greek scientist Archimedes. Photo: Swiss National Museum

The portrait of Prince John VII of Mecklenburg was retouched to make him a monk. Photo: Swiss National Museum

Infrared reflectography shows even more clearly that the monk had not always been a monk. Photo: Swiss National Museum