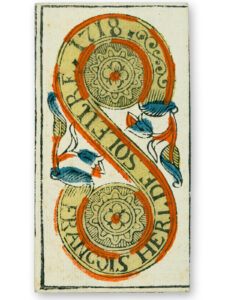

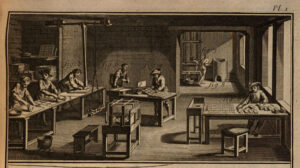

Solothurn, the cardmaking capital

In the 18th century, Solothurn was an important centre of playing card production. Throughout the Swiss Confederation almost everyone played with cards made in Solothurn, and the card designs produced there were also popular “beyond” the border.