The Register of Benefactors – an Early Modern book of sponsors

Sponsor boards are omnipresent at sporting, cultural and musical events these days. Even Einsiedeln Abbey received sponsorship. In return its sponsors found themselves in a manuscript known as the “Register of Benefactors”.

On Sunday, 24 April 1577, a raging fire ravaged the village and abbey in Einsiedeln. The devastation and sheer hardship prompted Abbot Ulrich Wittwiler to commission an elaborately designed parchment manuscript around ten years later. Wittwiler offered an entry in the register as well as salvation to everyone who supported the rebuilding of the abbey. The abbot was successful with his quest for sponsors. For almost 200 years hundreds of gifts were recorded meticulously in the manuscript.

When Ulrich Wittwiler became Abbot of Einsiedeln in 1585, the traces of the catastrophic fire were still very much in evidence. In the foreword to the Register of Benefactors, he complained about a “partly unbuilt and predominantly empty abbey”. The flames had destroyed not only the buildings and facilities, but also precious objects in the church and monastery rooms. Among them, as Wittwiler writes in the foreword, a “splendid large parchment register” in which sponsors and donors were recorded with details of their donations to the abbey.

And it was precisely this book which the abbot had in mind when he commissioned Einsiedeln schoolmaster and notary Leonhard Zingg to “set down in writing many beautiful things and benefactors” because “the human memory is stupid and weak”. Given that book printing and paper books had been commonplace and reasonably priced since the 15th century, the production of a parchment manuscript even back then was extremely costly and the register was valuable.

Still today the form and content of the Register of Benefactors give some suggestion of the huge importance attached to the manuscript. The cover of the binding is adorned with red, heavily abraded velvet. The traces of now disappeared, presumably silver studs are evident in the corners and in the middle. The body of the register comprises 200 sheets of parchment and four pieces of paper.

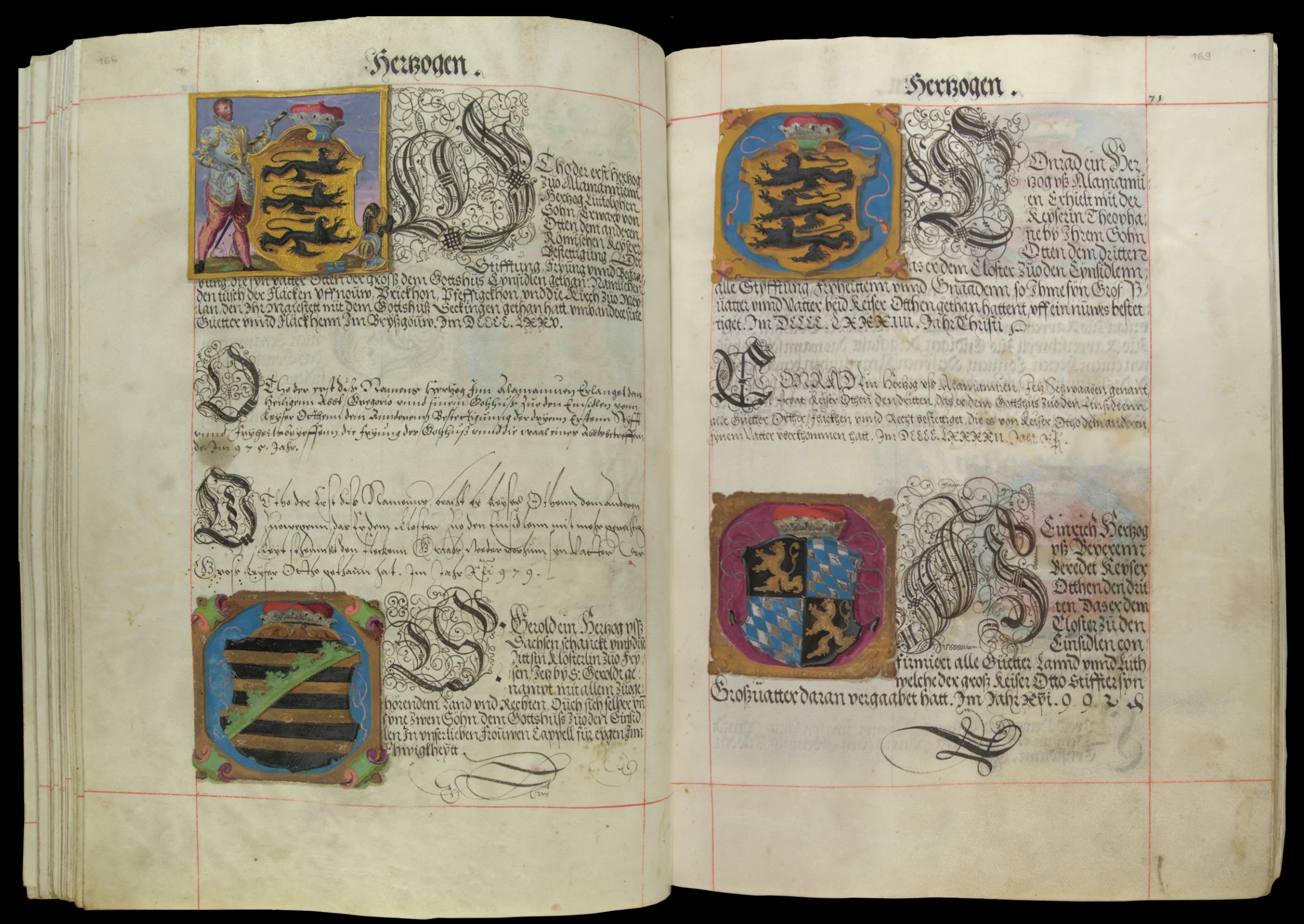

The manuscript contains four different sections. It opens with four magnificent, colourful pages of illustrations. The cover image is of the coat of arms of the person who commissioned it, Ulrich Wittwiler. There follow representations of Saint Meinrad, the Einsiedeln Chapel of Grace and the Angels’ Blessing, which is still an annual event. The illustration pages are followed by the foreword penned by Zingg in his stylish handwriting. In this, Abbot Wittwiler stresses the importance of donations and gifts for raising the reputation of the abbey in the middle of “lands dominated by sects”, i.e. protestant territories. Wittwiler promises the donors that the monastic community will think of them and pray for their salvation. After the foreword comes a chronicle of the abbey since it was founded in the 10th century, with brief biographies of the abbots. This section is adorned with the delicately crafted coats of arms of the abbots.

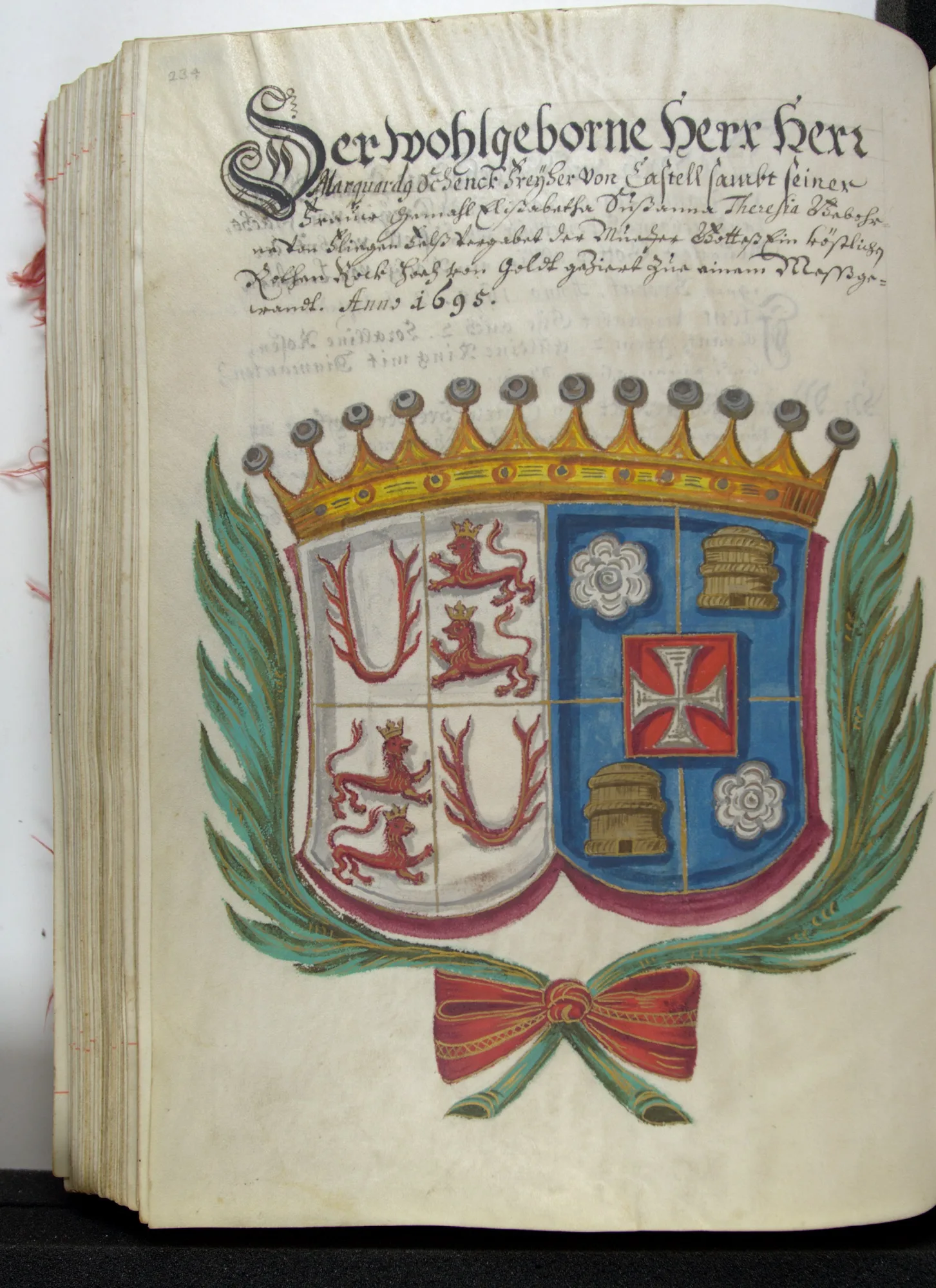

The actual directory of the donations and gifts, the “Catalogus”, consists of 340 pages. Around 80 pages are empty and were probably intended for future donations. Decorated with a variety of writings and heraldic representations, initials and embellishments, the highly organised catalogue consists of various parts. While the initial entries up to around 1620 were made by Zingg, well over 20 different writing styles can be discerned from then until the eve of the French Revolution in 1785. Spanning 1137 entries, the names of the donors were recorded meticulously, together with the date and nature of their gifts as well as the reasons in many cases.

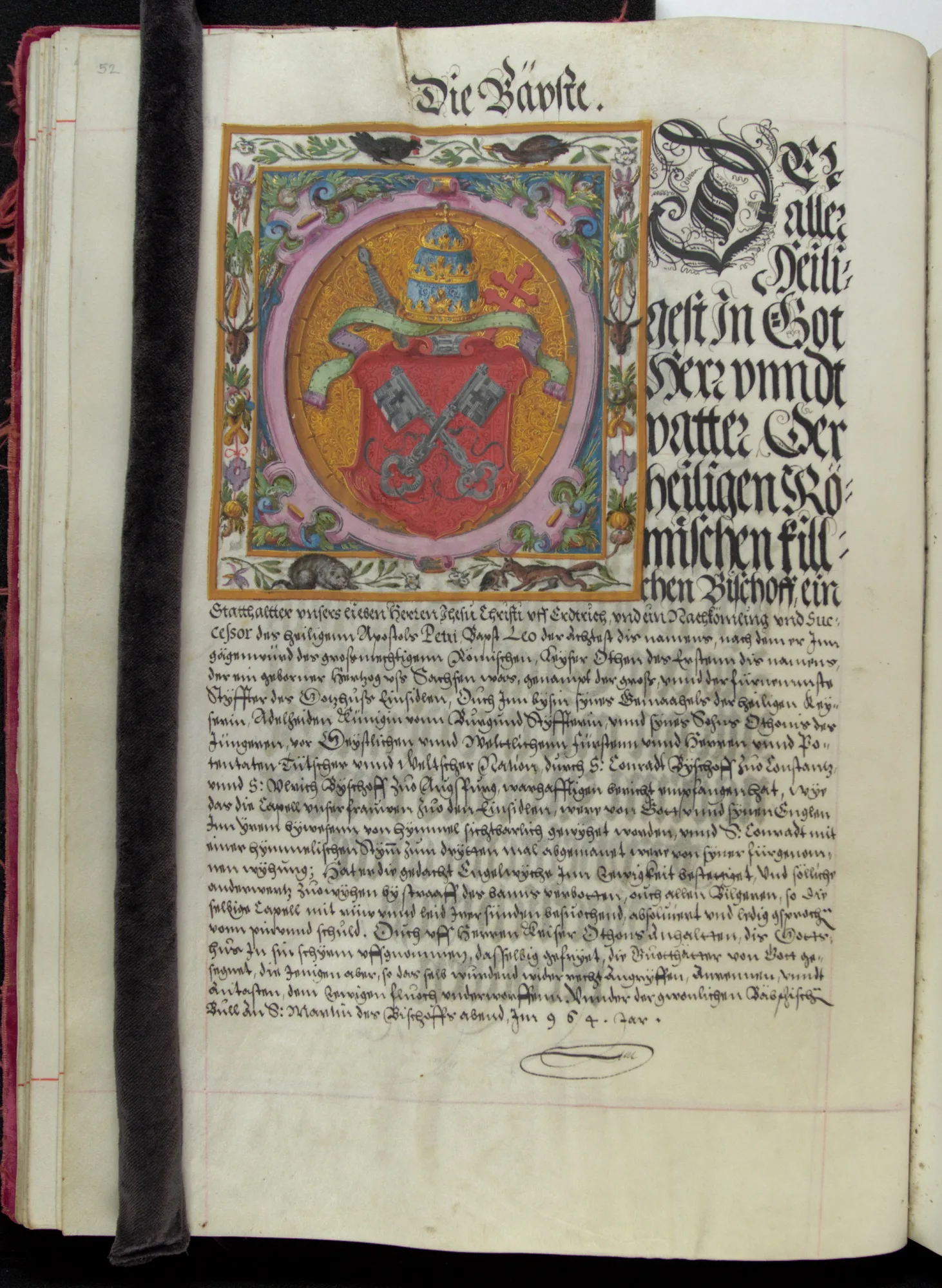

The “benefactors” are strictly hierarchically arranged in the catalogue and reflect almost the entire spectrum of Early Modern society. The entries relating to papal and imperial or royal donations read like a who’s who of spiritual and secular leaders. Numerous other entries name hundreds of unknown or even nameless people.

The gifts include assets and privileges, as well as material goods and money donations. While the former were mainly bestowed by popes or emperors, with evidence in the form of documents, other donors frequently brought material goods and money donations in person, while on a pilgrimage for instance. Almost 1000 entries relate to material goods, usually altar paraphernalia, some made from very precious and elaborately crafted materials. Alongside a large number of pieces of jewellery made from precious metal and decorated with precious stones, there are also quite mundane and sometimes strange items such as tableware and bedding, a horse and something that was probably a piece of music. The catalogue ends with a section entitled “Fire Tax”, which lists the gifts given to alleviate the hardship caused by the fire of 1577.

Abbot Ulrich Wittwiler, the person who commissioned the Register of Benefactors, was also among the donors and sponsors, a gesture which gained him worldly fame, if not heavenly salvation.

Einsiedeln Abbey. 1,000 Years of Pilgrimage

The Register of Benefactors is on show at the National Museum Zurich until 21 January 2018. Visitors can browse through it virtually. The exhibition presents the history of Einsiedeln Abbey and its pilgrimage, which spans more than 1000 years.

First page of the directory of papal gifts with apostolic coat of arms from the Register of Benefactors, page 52.

Gift from Marquard Schenck, Freiherr von Castell and his wife Elisabeth von Klingen with an alliance coat of arms, Register of Benefactors, page 234.

Representation of Saint Meinrad on his way to the Dark Forest, Register of Benefactors, page 6.

Exlibris with the coat of arms of Abbot Ulrich Wittwiler, flanked by Mary and Jesus and Saint Meinrad, Register of Benefactors, page 5.