Whose freedom?

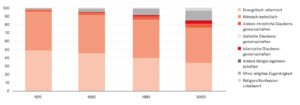

At one time the Muslim headscarf was a frequent source of heated debate. It can be seen as a barometer to gauge changing views of religious freedom.

Report on Swiss voters agreeing to the "burqa ban" in March 2021. YouTube / Reuters

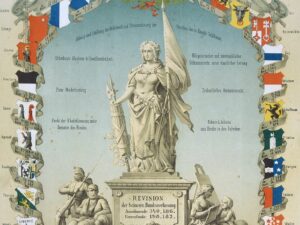

Every person has the right to choose freely their religion or their philosophical convictions, and to profess them alone or in community with others.