When colour television came to Switzerland

On 1 October 1968, the first scheduled television programme in colour was broadcast in Switzerland. The first colour image: a bouquet of flowers, still in black and white, suddenly blossomed into full colour. This historic TV event was preceded by tough wrangling over technical standards. Throughout Europe, there was disagreement over the standardisation of colour television technology. In Switzerland, the choice of a technical standard became a language issue.

As is so often the case with entertainment, it started in the USA, where colour television made its premiere way back in 1954. Since the colour reproduction was still sub-standard and colour TV receivers were expensive, the idea didn’t catch on straightaway. It wasn’t until the early 1960s that TV sets in America’s living rooms were increasingly flickering in colour. In Europe, it took a while longer before colour made its triumphal appearance on our television screens. The reason lay in a major disagreement over the standardisation of colour television technology. Countries had the choice between the NTSC (USA, Japan), PAL (Germany) and SECAM (France, USSR) systems. Each system was backed by well-connected stakeholder groups drawn from the nationally entrenched telecommunications industries. In 1965, officials and television technicians from 33 nations held a meeting in Vienna at the Conference of the International Radiocommunication Consultative Committee (CCIR) of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a special organisation of the United Nations. They tried to agree on a standard, but to no avail. The scenario was repeated a year later at a special conference in Oslo. Thus it was left to each European nation to decide on a TV standard for itself.

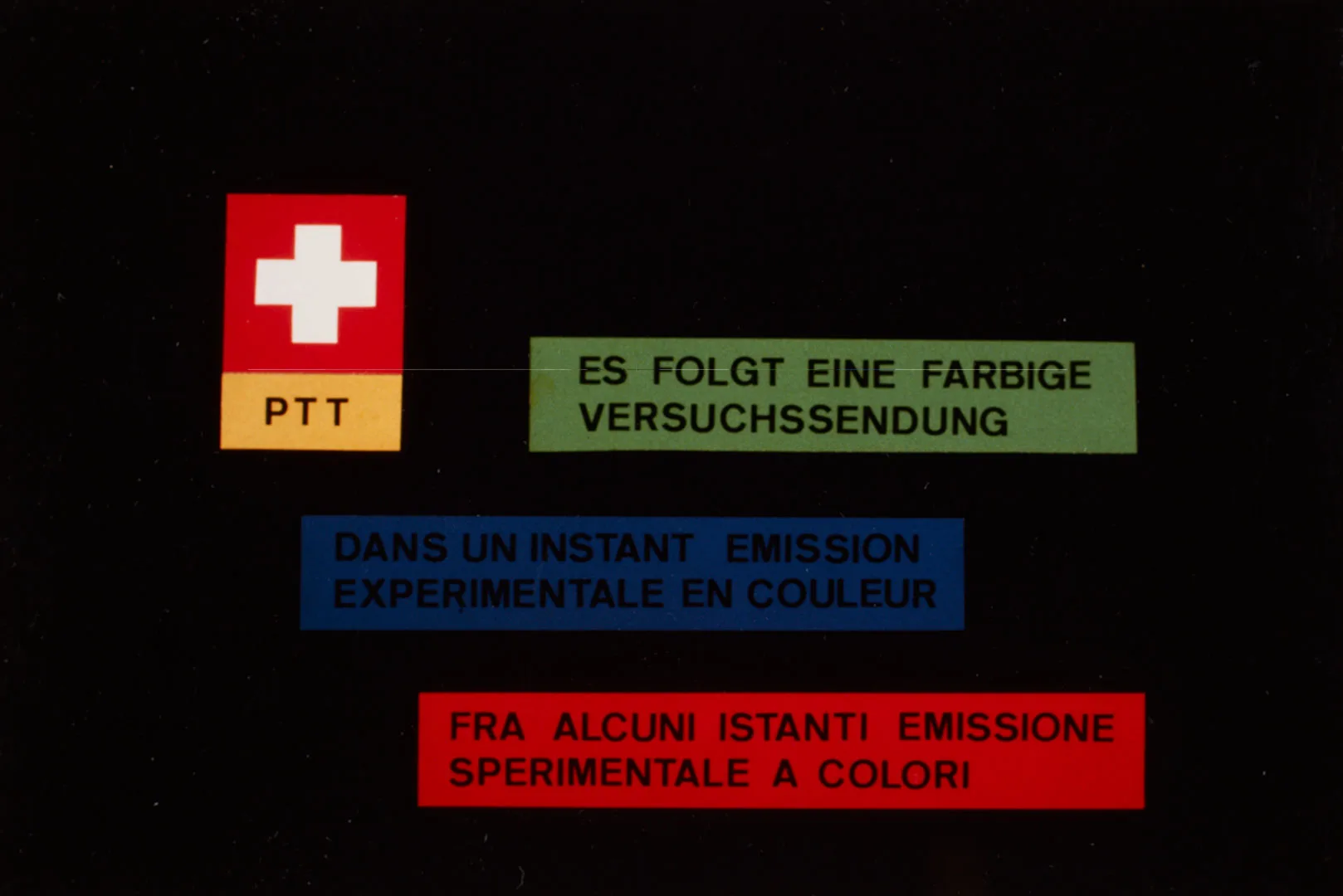

In Switzerland, the Confederation entrusted the technical aspects of television, such as transmission systems and studio equipment, to the state-owned enterprise PTT (Post-, Telefon- und Telegrafenbetriebe). The PTT engineers and technicians evaluated the three TV systems ‘unencumbered by industrial interests and questions of prestige’, according to PTT Director General Fritz Locher. The result was clear: between 1965 and 1967, the PTT argued on multiple occasions in favour of the PAL system. In measurements and test runs, the German system delivered the best transmission results. PAL was especially impressive in the Swiss Alps, where the transmission of TV signals through the air was a special challenge. In addition, most of the 800,000 black-and-white television sets in Switzerland were unable to receive SECAM. Was it reasonable to replace all those devices? The Federal Council agreed with the PTT experts, and on 15 August 1967 established PAL as the Swiss TV norm. But this Federal Council decision angered many inhabitants of the French-speaking Romandy region. In western Switzerland, people would now need to have colour television sets that were compatible with several different standards if they also wanted to receive programming from France. Their indignation was understandable: the first such sets arrived on the market in 1969 and cost about 4,000 francs – equivalent to 12,000 francs today.

After the Federal Council decision, PTT in particular had a lot of work to do. The television network and the makeshift studios needed to be technically upgraded and made ‘colour-ready’. In the 1960s, TV cable connections were not yet in widespread use, so the network relied on directional beam technology. Within a year and a half, the larger broadcasters (including Mont Pèlerin, Chasseral, Bantiger, Jungfraujoch, St. Chrischona, Uetliberg, Albis and Säntis), along with regional broadcasters and TV transmitters – 120 stations altogether – were ready to broadcast in colour. Several test broadcasts had already been transmitted in colour, such as, in August 1968, an episode of the quiz show ‘Dopplet oder nüt’ with Mäni Weber.

On 1 October 1968, the hour had come. Following the launch of colour television in West Germany, France, the UK and the Netherlands, colour TV signals were now also to be broadcast as standard in Switzerland. Marcel Bezençon, Director General of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SRG), gave the command: ‘Technique, que la couleur soit!’ [Technical team, let there be colour!] – and the bouquet of flowers in Studio Bellerive in Zurich was transmitted in colour. Comparatively few viewers were able to experience this TV event. At that point in time, only about 6,000 Swiss households had a colour TV. On the remaining 900,000 TV sets, the bouquet of flowers remained black, white and grey. Nevertheless, the step towards colour television was a state occasion: in addition to the bouquet of flowers in question, Federal Council member Roger Bonvin, head of the Federal Department of Transport and Energy, was also present at Studio Bellerive. Flanked by a Federal Council clerk, he declared the official launch of colour television in Switzerland, and in his speech expressed the hope that the colour on the screen would give television greater powers of persuasion and would thus make a significant contribution to understanding between peoples and nations. While the somewhat elderly gentlemen Bonvin, Bezençon, Locher and SRG Central President André Guinand represented the male world at this TV event, four young women took on the female role in the broadcast. The four pretty television announcers represented the national languages, and each was presented with a bouquet of roses by Federal Councillor Bonvin. The programme, billed as ‘an evening of colourful TV’, was then continued in the best federal tradition with TV productions from the four regions of the country. German-speaking Switzerland contributed the show ‘Holiday in Switzerland’ – a satire on tourism in the country. Ticino television presented ‘Il Laghetto di Muzzano’, a piece on water conservation using the example of the small lake near Lugano. French-speaking western Switzerland broadcast a folkloric piece from the linguistic border, ‘Le chanson de Fribourg’. Finally, for Romansch Switzerland there was a portrait of the painter Alois Carigiet.

The somewhat naive desire of Federal Councillor Bonvin – that colour television should foster understanding among peoples – was met. Where there was dismal failure with regard to the technical standards, European TV collaborations actually accomplished something. Since 1967/1968, half of Europe has been sitting in front of their TVs watching the Eurovision Song Contest (originally the ‘Grand Prix Eurovision de la Chanson’) or international sporting events such as the Olympic Games in colour, TV set permitting. But all the same, the TV event of the century was broadcast in black and white. When Neil Armstrong became the first person to walk on the moon on 20 July 1969, the live images were transmitted from the moon in black and white.

Between 1968 and 1970, further improvements were made to the colour television infrastructure. By the end of 1970, the SRG was broadcasting 40% of programming hours in colour. For the transmission of events outside the TV studios, in 1970 the SRG obtained large television broadcasting vehicles. Ski racing and football games could now also be transmitted in colour. The latter presented technicians with challenges that are difficult to imagine today. As technician Günter Kaiser recalled in a television programme, on the pitch they had to align the cameras using a huge test card mounted on cardboard. The pitch had to be shown in the same shade of green in all images. In the studio too, the problems were sometimes in the detail. As television announcer Dorothea Furrer – popularly known to the Swiss simply as ‘Schätzli der Nation’ (Switzerland’s national treasure) – reported, in the early days a summery tanned complexion caused problems. When shown in colour, it appeared as an ‘ugly shade of grey’.

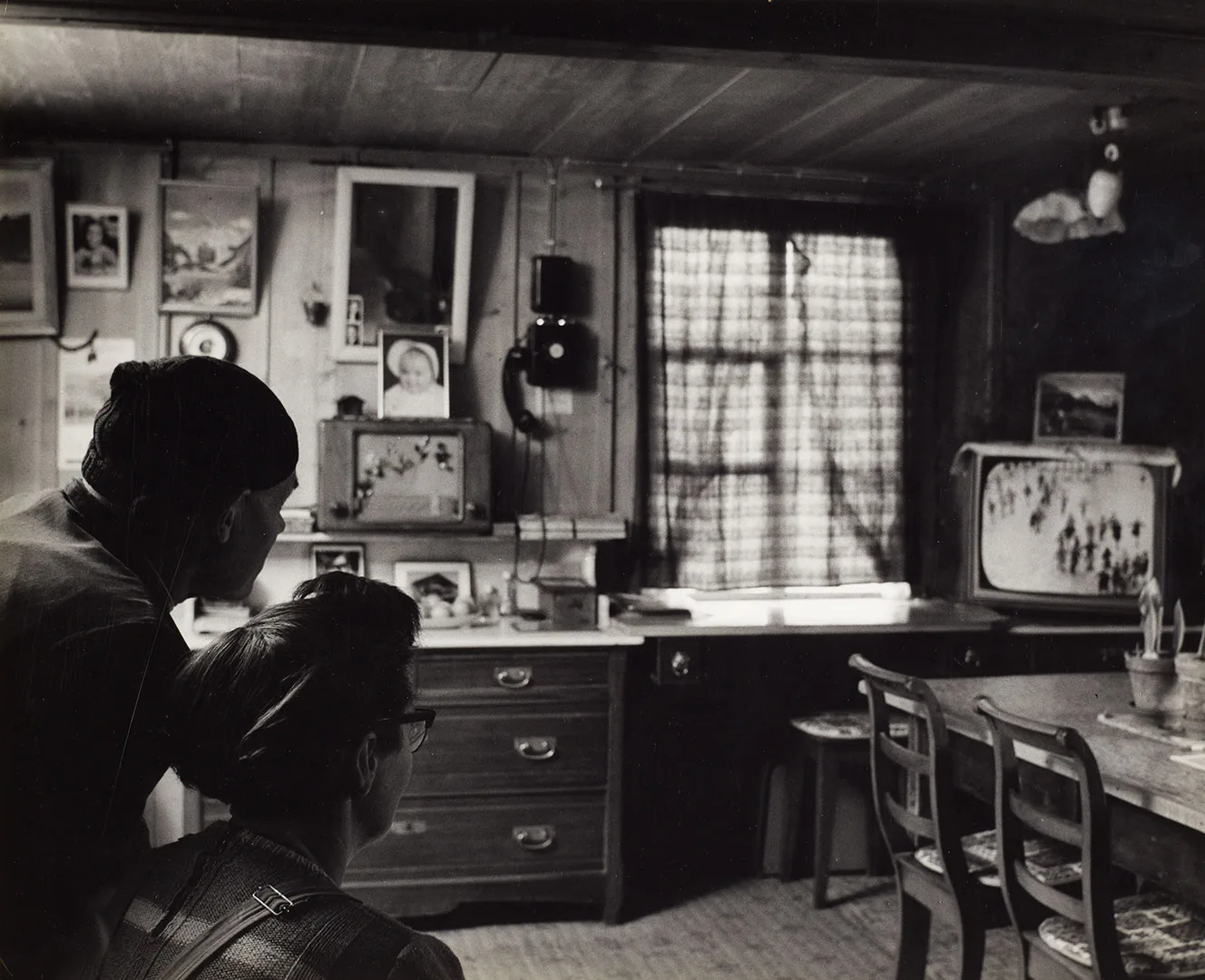

By 1977, the switchover to colour television was largely completed, having thus taken almost 10 years. In that year, the last Ticino studio in Comano also went on air in colour. At the end of 1969, just 3% of television sets in Switzerland were able to receive colour signals; ten years later, that figure was about 60%. Many TV users were cautious about switching to colour television. For a lot of families, it was an issue of first paying off their expensively purchased black-and-white sets. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the last of those sets disappeared from living rooms and found themselves on the scrap heap or, occasionally, in museum collections.