From ‘Landjäger’ to traffic cop

How the modern-day police force evolved out of goods inspections at medieval markets and the expulsion of beggars from the nation’s territory.

The history of the police in Switzerland is also the history of the formation of our modern liberal state. The occupation of police officer in the modern sense has thus existed only for about 150 years. Murder, fraud and theft, on the other hand, are as old as humankind, and so is the function of the police officer. For centuries, the boundaries between the administration, the military, the police and the judiciary were quite fluid, and policing power was often in the hands of the ruling elite, or even an individual ruler.

Societies in ancient Europe needed law enforcers and crimefighters. In ancient Rome, the army was primarily responsible for keeping order in the markets and streets. After the fall of Rome, the political system in Europe largely collapsed. It was not until Charlemagne (768-814) reorganised Europe that there was once again a functioning body politic, and therefore the function of police officer, on the territory of what is now Switzerland.

During the High Middle Ages, authorities were formed whose purpose was to maintain order in the cities. Entry to towns and cities was strictly regulated and was secured by city walls and gates. Gatekeepers controlled who came in and who went out, and night watchmen patrolled the narrow streets during the hours of darkness. Marketplace inspectors, or ‘Schaumeisters’, checked the quality of the goods in the markets; other civil servants monitored compliance with fire safety rules or health regulations. In the event of any criminal offence, low-level municipal officials called ‘Stadtknechte’ brought the wrongdoers before the town council.

The word ‘police’ is derived from the term ‘gute Policey’, or ‘good ordinance’. Initially, this term designated not an administrative unit or a function, but an aim: living together in a society in an orderly and well-regulated manner. The increasingly comprehensive regulation of all possible aspects in the life of an ordinary citizen reached its peak in the absolutist police state of the 17th and 18th centuries. The ‘Policey’ was then responsible for enforcing and monitoring these rules. Vestiges of the evolution of this concept can be found in the now obsolete terms ‘Fremdenpolizei’ (immigration police), ‘Baupolizei’ (building inspection department) or ‘Feuerpolizei’ (fire service).

Also the police's armament has changed over the centuries. Pistol of the police of Neuchâtel, 1840-1860.

Swiss national museum

‘Landjäger’: not a prestigious job

Bands of thieves, vagrants and beggars have played a key role in the emergence of a modern policing system in Switzerland since the 15th century. Able-bodied men were called on to work as ‘Landjäger’ or gendarmes to expel the ‘riff-raff’ from the nation’s territory. The Landjäger were soldiers who had served in the military abroad. However, the hunt for beggars and thieves remained largely ineffective, as the borders were not guarded and the miscreants were able to sneak back in immediately. And these Landjäger, coarsened by their experience of war, were not known for their sensitivity. Gradually, the Landjäger also took over tasks which had previously been carried out by various other authorities.

Up until the founding of the Federal state and the adoption of liberal constitutions in the cantons, the Landjäger had a bad reputation. The liberal spirit of the times in the second half of the 19th century was at odds with the poorly paid, rough and often tyrannical and autocratic Landjäger corps. The job of Landjäger was a disreputable one, and not for any self-respecting citizen. There was therefore a ‘dearth of honest men who would stoop to doing such work’, claimed a Zurich report in 1728. This in turn promoted corruption and despotism among the law enforcers. As a result, in the Canton of Zurich, for example, by 1864 most of the Landjäger corps had been dismissed, the pay had improved and stricter policing laws and service regulations had been issued.

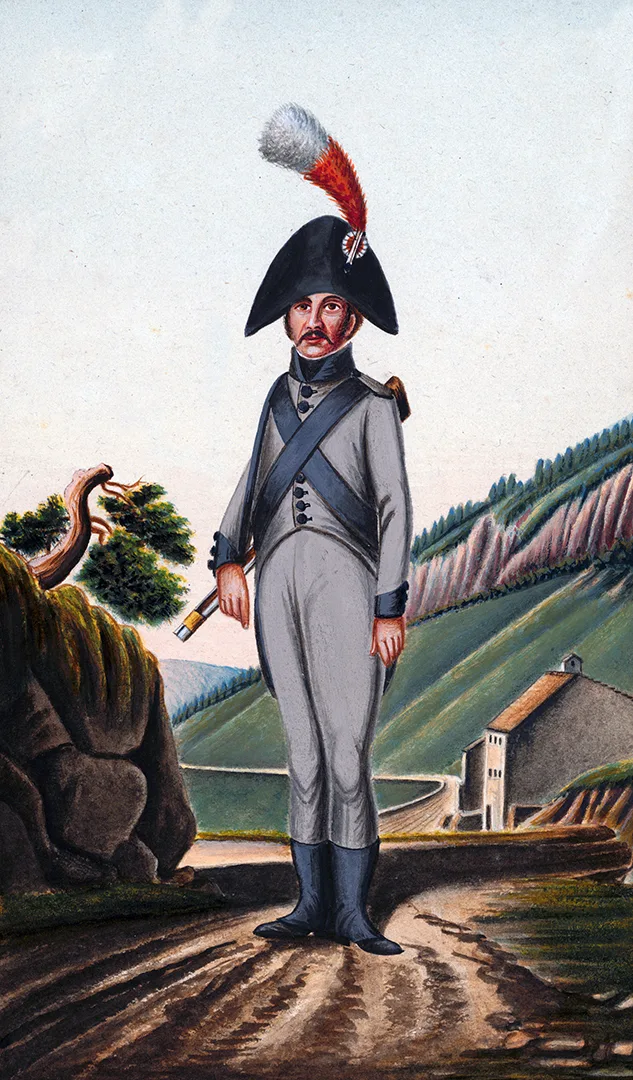

'Landjäger' around 1800.

Swiss national museum

'Landjäger' from Solothurn, around 1813.

Swiss national museum

Searches and identification

The prevailing mistrust of outsiders and strangers at the beginning of the 19th century led to the creation of identification papers and travel documents. Anyone who was travelling needed a permit from the authorities. Identity documents legitimised the purpose and duration of travel, and it was advantageous to carry these papers with you if you did not wish to be expelled as a vagrant. The cantons also issued passports for travel abroad or to other cantons. To enable the authorities to identify suspect persons or those who had already been refused admittance, personal description booklets, which the cantons exchanged among themselves, came into use.

Industrialisation and technical progress also had a decisive impact on the policing system. From 1900, police forces started taking the physical measurements of suspects, and in 1913 the use of fingerprints came in. Radio, telephone and the advent of the motor car further changed the way the police worked. From the 1950s onwards, specialised traffic police units were created, and from the 1970s task forces to combat serious crime. Just as society is changing, and with it our security needs and crime itself, so too must the police constantly adapt to these changes.

Officers of the police of Saint Gallen, 1937.

Photo: Kantonspolizei SG/Facebook

An officer checks the papers of a driver, around 1946.

ASL/Swiss national museum

A traffic policeman in action in Zurich, around 1960.

ASL/Swiss national museum