Swiss National Museum

The Rue du Parc synagogue in La Chaux-de-Fonds

Jewish clock and watch manufacturers played a significant role in the recovery and modernisation of the watch industry in the Jura. The largest synagogue in Switzerland was built in La Chaux-de-Fonds 125 years ago. It stands as a landmark in this success story.

“In La Chaux-de-Fonds, no certificate of baptism was required as an ‘entry ticket’ to middle-class society. At the turn of the century watchmaking skills, and more importantly wealth and a bourgeois lifestyle, were enough in the town that was the heart of Switzerland’s watch industry,” writes Stefanie Mahrer in her book Handwerk der Moderne. Jüdische Uhrmacher und Uhrenunternehmer im Neuenburger Jura 1800-1914 (Modern crafts and trades: Jewish watchmakers and watchmaking businesses in the Neuchâtel Jura 1800-1914). When the Comité de Communauté Israélite of La Chaux-de-Fonds decided, in 1890, to build a prestigious house of prayer, clearly identifiable as a synagogue, in the middle of the town, there were 800 men and women of the Jewish faith resident in the Neuchâtel metropolis, renowned for its watchmaking industry. Just a few years later, at almost the same time as the formal opening of the new synagogue on Rue du Parc, the Jewish population reached its peak. Around 1900, the city of La Chaux-de-Fonds had the highest percentage of Jewish inhabitants in Switzerland.

The growth of the Jewish community of La Chaux-de-Fonds had its origins in the 1857 abolition of the ban on Jewish settlement. A steady stream of hardworking Jewish immigrants began coming in from nearby Sundgau in Alsace. And when, from 1866, Jews were also able to obtain Swiss citizenship, the flourishing city became even more attractive. The new citizens, with names like Schwob, Bloch, Didisheim, Ditesheim, Weill and Dreyfuss, brought with them a new energy and new ideas, because they realised that the traditional workshops of the ‘fabrique horlogère collective’, which were scattered throughout the town and functioned in a fragmented way, could no longer compete with the demands of a rapidly modernising watchmaking industry. The traditional method of assemblage was dying out.

JEWISH MODERNISATION OF THE WATCHMAKING INDUSTRY

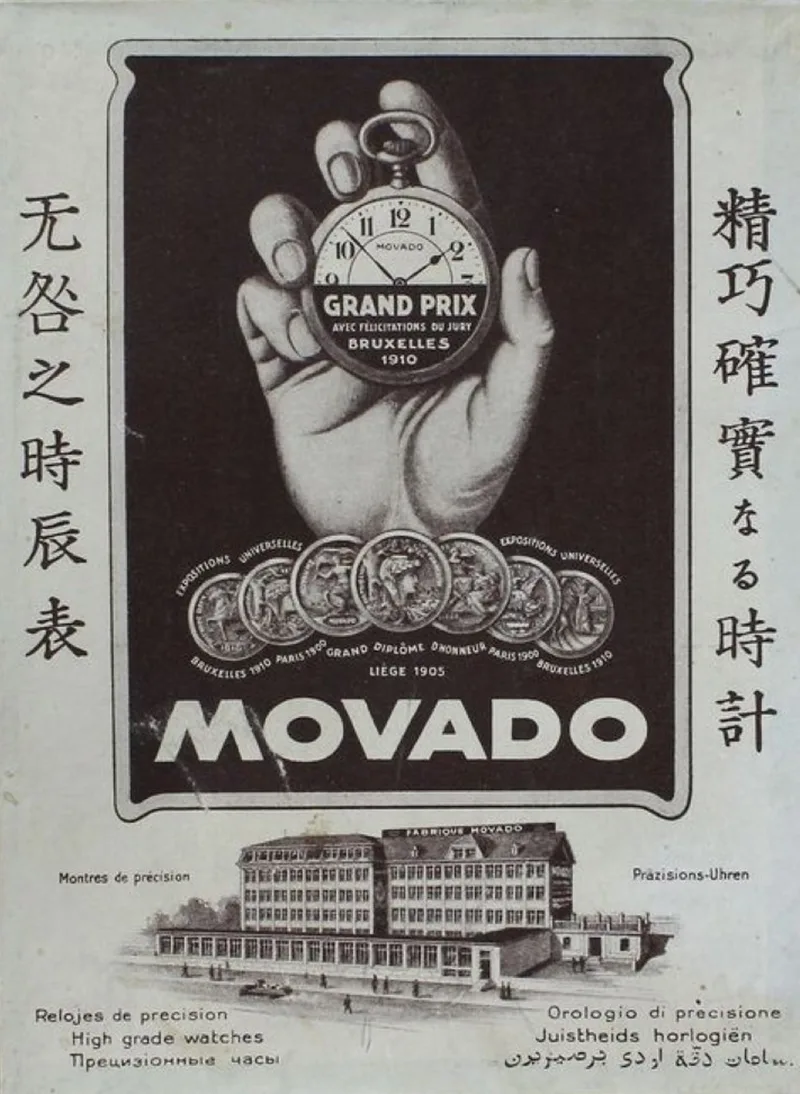

The way out of the first major watchmaking crisis in the Jura led to the setting up of syndicates, international trading establishments, and the building of watch factories capable of high-volume production for the global market. The recently immigrated Jewish entrepreneurs and watchmakers played a significant role in modernising horology in the region. They created innovative collections, financed modern factories and set up international networks. They gave their brands the names Eterna and Movado, borrowed from the artificial language Esperanto. An example of this dynamic growth is the factory of the Tavannes Watch Co., which could produce up to 2,500 watches a day. In 1910, four out of five companies with taxable assets of more than 20,000 francs in La Chaux-de-Fonds were in Jewish ownership.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Jewish entrepreneurs were among the civic and economic elite of the watchmaking capital of Neuchâtel, and today, their grand villas, once-modern factory architecture and the largest synagogue in Switzerland are still a visible sign of that prestige.

Watch box from Movado, around 1950.

Swiss National Museum

In actual fact, the new house of worship was to have been built in the mid-1880s. But a wave of politically fuelled riots, in which Jewish businesses were vandalised and dolls emblazoned with the names of Jewish factory owners were hanged and set alight, caused the community to postpone construction. It was not until 1892 that the project was offered for competitive tender in the Schweizerisches Baublatt construction journal. The community took pains to be as publicly open and transparent as possible about its plans, because the new synagogue building was intended from the outset to be seen as a highly visible contribution to the town’s urban culture. The contract was awarded to architect Richard Kuder, who had designed prestigious major buildings first in Strasbourg and later also in Zurich (the Rentenanstalt on the Alpenquai, the Schützenhaus Albisgüetli, and the stock exchange on Bleicherweg).

The foundation stone was laid on 28 June 1894. In his speech the community’s rabbi, Jules Wolff, emphasised that the community would now finally have a religious building that would be fit for purpose and meet the needs of the large number of Jewish citizens living in La Chaux-de-Fonds. In keeping with the synagogue architecture of the late 19th century, Kuder designed a central structure with Byzantine and Romanesque elements for La Chaux-de-Fonds. The high dome, covered with enamelled shingles and visible from far and wide, proudly proclaimed the affluence and the upper-class self-image of the thriving thousand-strong community.

The synagogue of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Wikimedia