Archive of the Basel Mission, Basel

On God’s business in India

From 1834 onwards, missionaries from Basel headed to India in their droves to convert the indigenous population to Christianity. The Basel Mission not only founded schools and hospitals in India, but also set up weaving mills and brickworks where the missionaries employed their Indian converts.

She was ‘passionately sober’, wrote the author Hermann Hesse about his grandmother Julie Gundert-Dubois, one of the first female Basel missionaries in India – and this paradoxical characterisation could probably be ascribed to other missionaries as well. Even in their letters of motivation, there was often a mismatch between Protestant austerity, and a bold spirit of discovery.

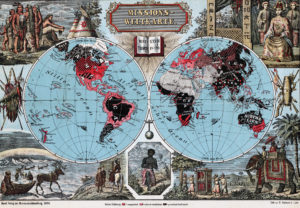

The Basel Mission was founded in 1815 by devout members of Basel’s wealthy upper-middle classes, and pietists from southern Germany. From 1828, the organisation started sending its own missionaries to the Gold Coast in Africa – present-day Ghana – and from 1834 to southern India. Mission stations in China, Cameroon and Indonesia followed. The early missionaries took enormous risks to spread what they believed to be the world’s only true religion, to rescue ‘lost souls’ and save them from idolatry and eternal damnation. The long journey by ship and ox cart, the unaccustomed climate and diseases were often life-threatening, and even hostile natives could pose a threat.

Somewhere between cultural paternalism and promoting the indigenous culture

The Mission’s workers sought not only to convert the local populace to their religion, but also to introduce the achievements of European civilisation, such as infirmaries and basic education – but always in the arrogant belief that, including for the local people in the areas where the Mission operated, the missionaries’ own way of life was the only true path to salvation. But for all that, the Basler Mission was not a colonial power seeking to forcibly impose its religion and ideology on the native population. This is evident, among other things, from the fact that some missionaries, both men and women, studied local languages intensively, published dictionaries and produced numerous translations, and not only of Bible texts. Basel missionaries did more than just work to improve literacy among the natives – often, they themselves became deeply involved with the local culture. Missionary Hermann Gundert, Hermann Hesse’s grandfather, was held in such high regard for his works on south India’s Malayalam language that it was said in India that he was ‘an Indian who was born in Germany by mistake’. A statue of him was erected in the city of Thalassery.

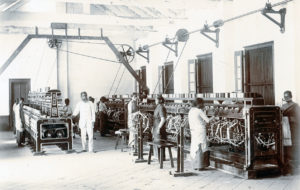

The Mission also got involved in the local economy – and profited from this involvement, by combining charitable interests and economic ones. For example, from the 1840s the Mission created jobs for its Indian converts in its own brickworks and weaving mills, and built up a flourishing trade in cocoa and palm oil from West Africa. In 1859 the organisation established its own public limited company, the Missions-Handlungs-Gesellschaft.

Hermann Hesse’s grandparents, Hermann Gundert from Stuttgart and the Swiss Julie Dubois, met through the Mission’s work, married and together established and developed the mission in Tellicherry, now Thalassery.

Archive of the Basel Mission, Basel

Weaving mill in Calicut (now Kozhikode), Kerala, late 19th century. In weaving mills like this, Indians who embraced the Christian faith found work and a new social environment.

Archive of the Basel Mission, Basel

‘Mission brides’

The exclusively single missionaries sent to the Mission area expressed the desire to marry, for a variety of reasons: to model for the indigenous population an exemplary Christian marriage, to be helped in their missionary work, or simply to have a companion by their side. For women, marrying a missionary was for a long time the only way to work in the Mission. The Julie Dubois mentioned above, who already lived in India, married the missionary Hermann Gundert only on condition that she be able to stay in India and work as a missionary. However, the selection of single European women in the Mission areas was scarce, and so a less romantic marriage practice developed between missionaries overseas and ‘mission brides’ in Switzerland and southern Germany. The committee in Basel selected suitable women and sent them off, equipped with a photo of their unknown husband-to-be, to the remote Mission area. Although interpreted by both parties as ‘answering God’s call’, the decision of these women to enter into a Mission marriage was often driven also by a thirst for adventure and a desire to escape from the narrow and strictly circumscribed lives they led in Switzerland. If the missionary did not meet the young woman’s expectations – or if he looked nothing like his photo – she was free to board a ship for home a few weeks later.

Missionary couple with staff, between 1901 and 1914, Calicut (now Kozhikode). The missionary couple was supposed to represent the European Christian ideal of marriage and family. They lived together with local staff such as cooks, maids and domestic servants.

Archive of the Basel Mission, Basel

‘A benevolent civilisation’?

The fact that the men and women who worked for the Mission were often inspired by the desire to make the world better, more moral and fairer was also reflected in their, for the most part, unbending rejection of slavery and the Indian caste system, which codified inequality right from birth. At the same time, the attitude of the missionaries to the indigenous population was very paternalistic, and they continued to cling to European ways of thinking. The Basel Mission considered the Protestant way of life to be superior to all others, and worked to mould the people in the Mission territories according to its own model. While the desire to become a missionary was often driven in part by a ‘child-like compassion for the poor heathens’, there was a lack of tolerance for people who did not wish to accept Christian mercy and who held fast ‘with unspeakable tenacity or indifference to their old ways’, as missionary Gustav Peter noted in 1897. The Basel missionaries only really approved of and engaged with the everyday lives of the indigenous people if the way they lived did not run counter to the missionaries’ own ideas and aims.

Medical station in Calicut (now Kozhikode) between 1900 and 1902. In 1886 a missionary who had studied medicine in Basel returned to southern India as the first missionary doctor. Medical stations were established in Kozhikode and Bettigeri.

Archive of the Basel Mission, Basel