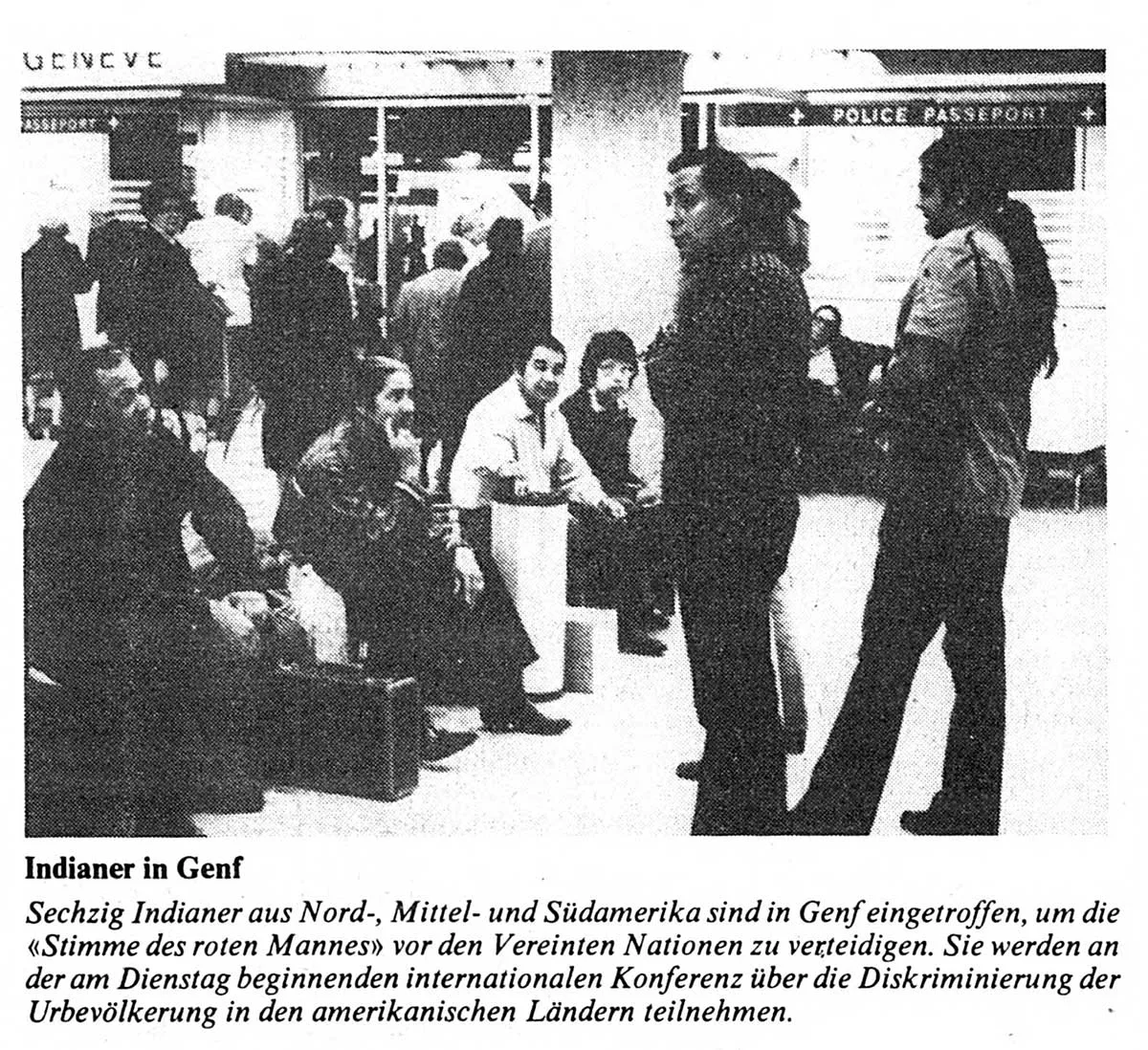

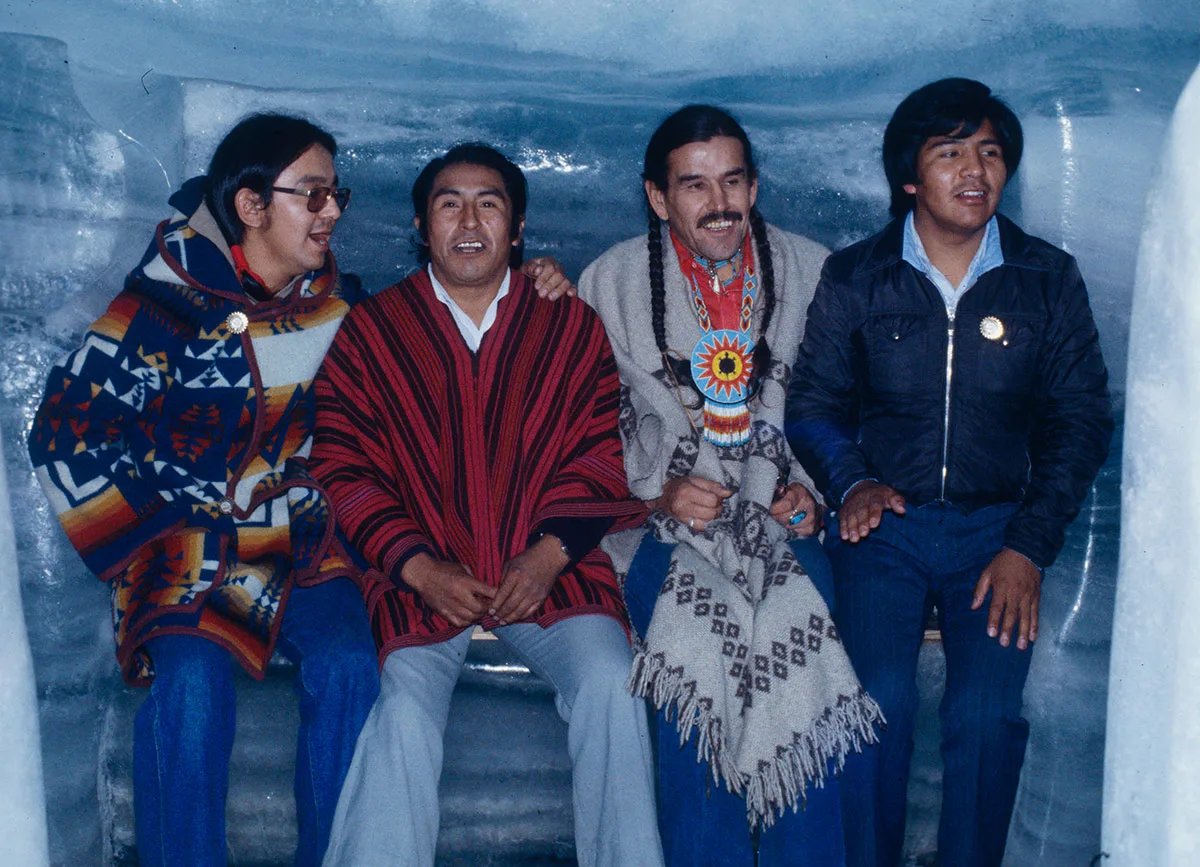

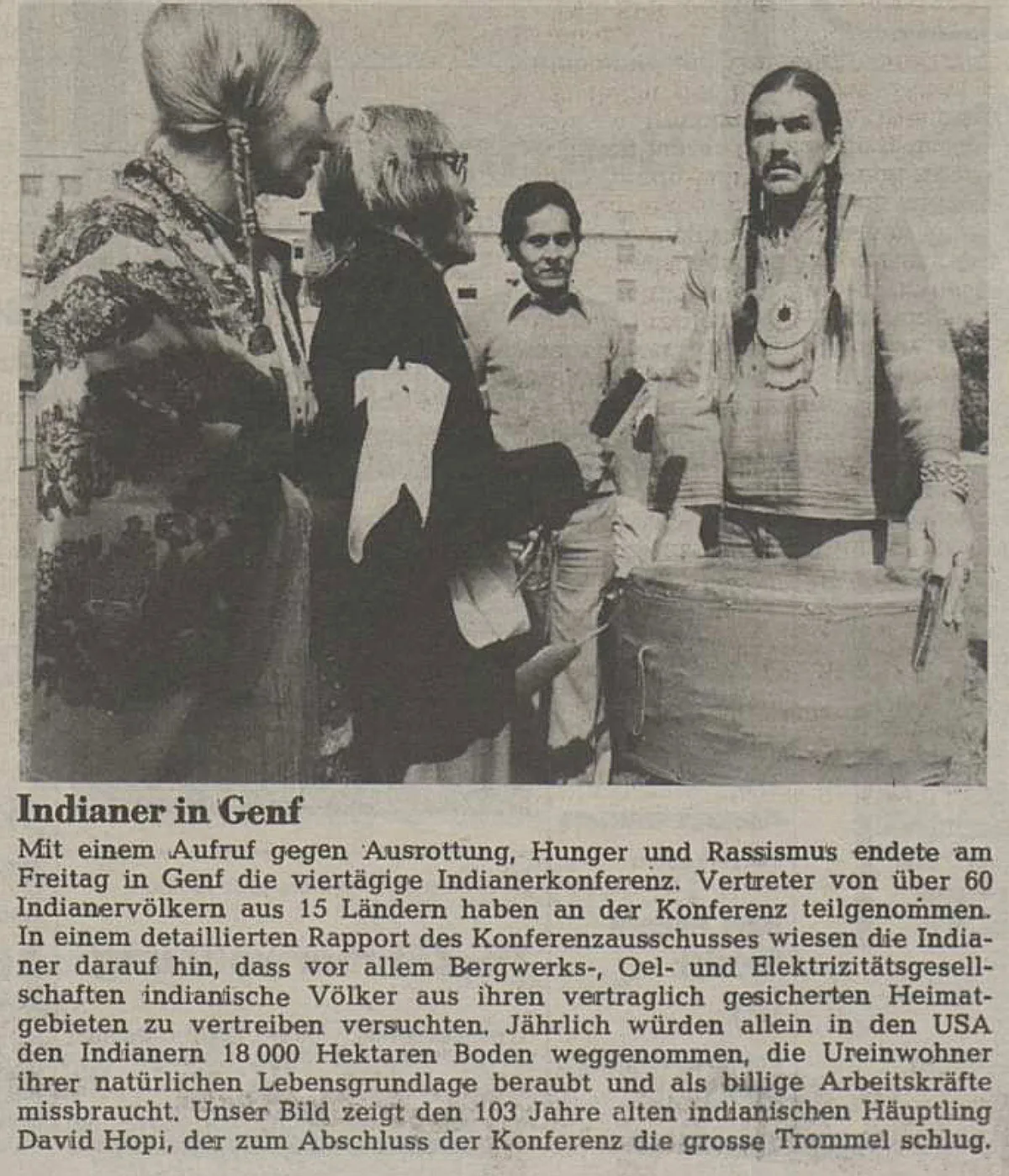

Switzerland’s tradition of supporting indigenous resistance

Resistance movements of indigenous organisations and societies have traditionally found a route through Switzerland. This is connected with the presence of the UN headquarters in Geneva. But there’s more to it than that.