A Swiss Confederate propagandist

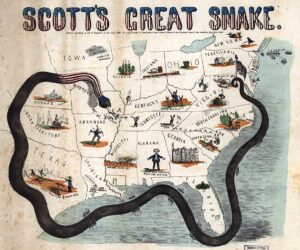

The life of Henry Hotze is largely unknown in Switzerland. Born in Zürich, Hotze emigrated to the United States. Later, he became the Confederacy's chief propagandist in Europe during the U.S. Civil War.

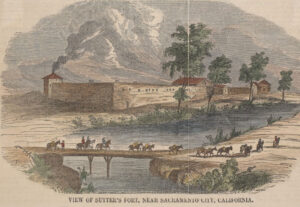

A Swiss-Southern Gentleman in Mobile

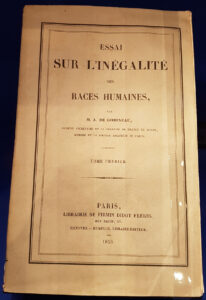

I consider it therefore established beyond dispute that a certain general physical conformation is productive of corresponding mental characteristics.

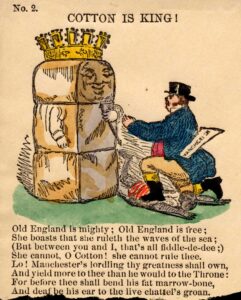

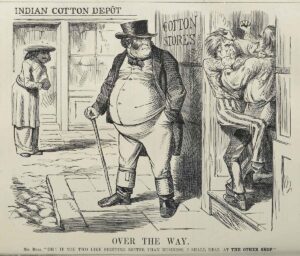

King Cotton’s Failure and Britain’s Importance

The Confederate’s Chief Propagandist in London

I think I may say without conceit that with my connections and my knowledge of the machinery of the press, I can ensure a simultaneous publicity in England and on the Continent, which even the [London] Times cannot equal.