How the Nazis cracked the Enigma

Why were the Germans able to listen in on Switzerland’s encrypted radio communications so easily during World War II? Secret documents released by the US have solved the mystery.

Autumn 1948. The Second World War ended two and a half years ago. At this point, a lengthy document is received in Bern. It was written by a coding specialist who dealt with encrypted Swiss radio messages on the German side during the war. The content: Nazi Germany was able to eavesdrop effortlessly on Switzerland’s encrypted radio communications! That sounds surprising, but even then the news wasn’t much of a shock for Switzerland.

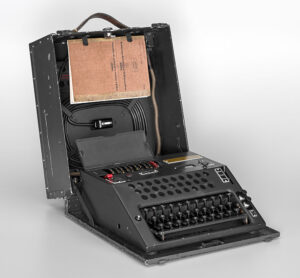

It’s important to remember the following: Switzerland used German encryption technology during World War II. The famous Enigma cipher machine, which was freely available on the market before the war, was used. However, it was mainly a less secure variant, the Enigma-K, that was openly sold.

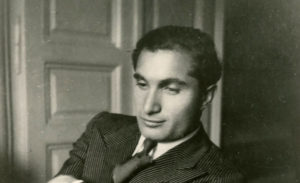

The author of the document was one Bruno Kröger. It was written in Kaufbeuren in Bavaria. Kröger explains in detail how to crack the Swiss Enigma. The author says that it took five to six workers several weeks just to decrypt the first cylinder. However, the other two cylinders were then able to be deciphered within a few days. He concludes: “In any case, in its present state there is no possibility for the Enigma Type K cipher machine to be used in such a way that it is capable of meeting security requirements.” Bruno Kröger then goes much further, and attempts to establish general rules for the security of an encryption process. Only at the end of the document does he get to the point of his message: he is simply looking for work, and is offering Switzerland his services as a cryptography expert.

Others were also listening in

For a long time the document was not in Switzerland’s Federal archives; it was only held by the Swiss Army’s cryptography specialists. From today’s perspective, a number of questions arise: Is the document genuine? Is the method described for decryption correct? How did Switzerland react at the time? Who was Bruno Kröger?

The cryptologist Frode Weierud stated in 2012: “The method described by Bruno Kröger for decrypting the Enigma K is correct and is similar to the methods used by the British at Bletchley Park.” Switzerland considered the document to be authentic at the time. The information wasn’t entirely new, however. Even during the war, people were already aware of the machine’s weaknesses. It later turned out that not only the Germans, but also the Poles, the British and the Americans were able to read Switzerland’s secrets almost effortlessly! While World War II was still going on, work started on developing the country’s own encryption machine that would no longer have these shortcomings. It was called Nema – an abbreviation for ‘New Machine’. However, the Nema didn’t come into use until after World War II.

Bletchley Park

The name Bruno Kröger first appeared in a document published in 1997. It was a set of records from the research office of the Reich’s aviation unit, one of the numerous intelligence organisations active during the Third Reich. In June 2010 the US intelligence service, the NSA, declassified further documents from World War II. This time it was a substantial report, comprising more than 1,000 pages, which was even published on the internet and can still be accessed today. In places it reads like a detective novel!

One of the key findings of the report by the Target Intelligence Committee (TICOM), a US-British organisation tasked with cracking German codes during World War II, was the discovery that German cryptanalysts were unable to read cryptography systems at the highest level. And so the Third Reich had no idea of the huge decryption operation going on at Bletchley Park in England, where hundreds of men and women worked day and night to decipher Germany’s secret radio communications.

Back to the question of who Bruno Kröger was. The name appears several times in the TICOM report in connection with the research office. This research office was an agency of the Nazi secret services, and dealt with the evaluation of telephone, telegraph and radio communications. It was under the control of Hermann Göring (1893 - 1946). Towards the end of the war, the supreme commander of the Luftwaffe had his research office relocated from Berlin to Kaufbeuren. After reading this report, there is no longer any doubt about who Bruno Kröger was: a cryptography specialist for an intelligence service of the Third Reich who was captured by the Americans in Kaufbeuren, where he gave an account of his activities and contacts. He must have written the report for the Americans – Switzerland only received a copy of the document. The mathematician Erich Hüttenhain (1905 - 1990) also worked in the same service. He was so important for the USA that he was taken to America by US troops after the war. He later became the leading German cryptologist!

The file on the subject of Bruno Kröger and Switzerland is not yet closed. A search for the term TICOM in US archives brings up several hundred reports, mostly interviews. They have not yet been evaluated. We don’t know what Bruno Kröger did after 1948. Perhaps the answer is somewhere in these documents.