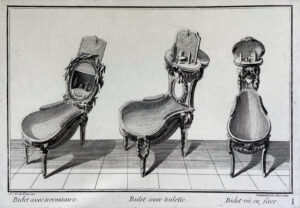

The bidet – furniture designed for cleansing the ‘delicate parts of the body’

300 years ago, a diverse array of special furniture designed for personal hygiene began to appear in the bedrooms and boudoirs of the French aristocracy. Among these was the ‘cleanliness seat’ – the bidet.

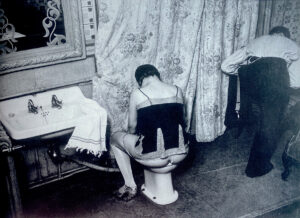

Elaborate 'morning toilette' in the boudoir

The triumphal procession of the 'little wooden horse'

A piece of furniture with an erotic component

For many, an object of shame