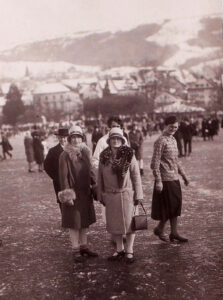

Eton crop, or traditional headwear?

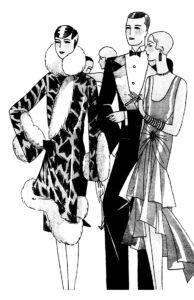

Short bobbed haircuts, figure-hugging skirts, flat shoes – the new fashions of the 1920s were wildly popular, but they also had their avowed opponents. Seeking a return to the values of the past, these groups set about re-establishing Switzerland’s long-dormant customs of traditional dress.

New role, new fashion

Short hair and lipstick

Scathing criticism and the anti-fashion movement

Traditional costumes also popular in the city