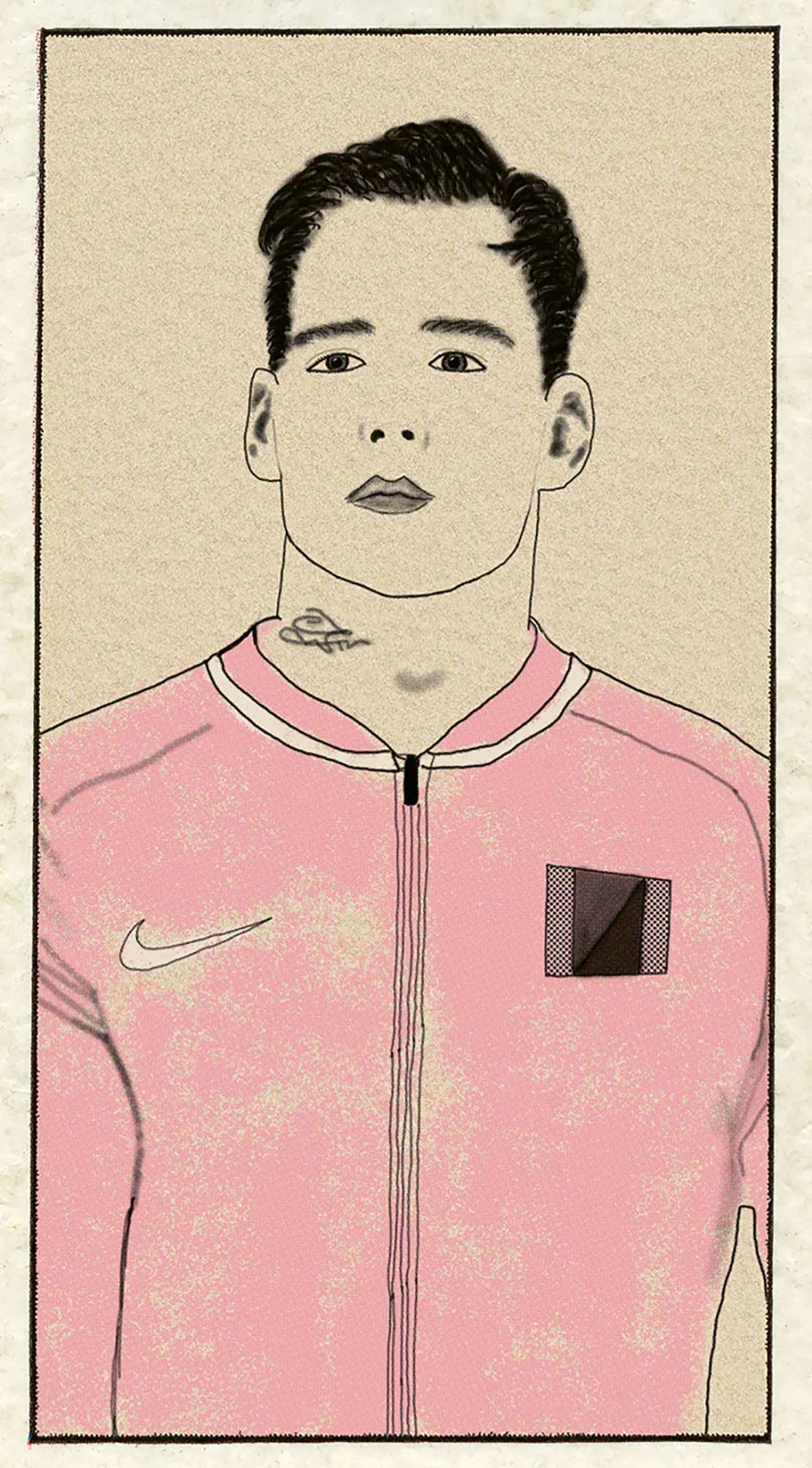

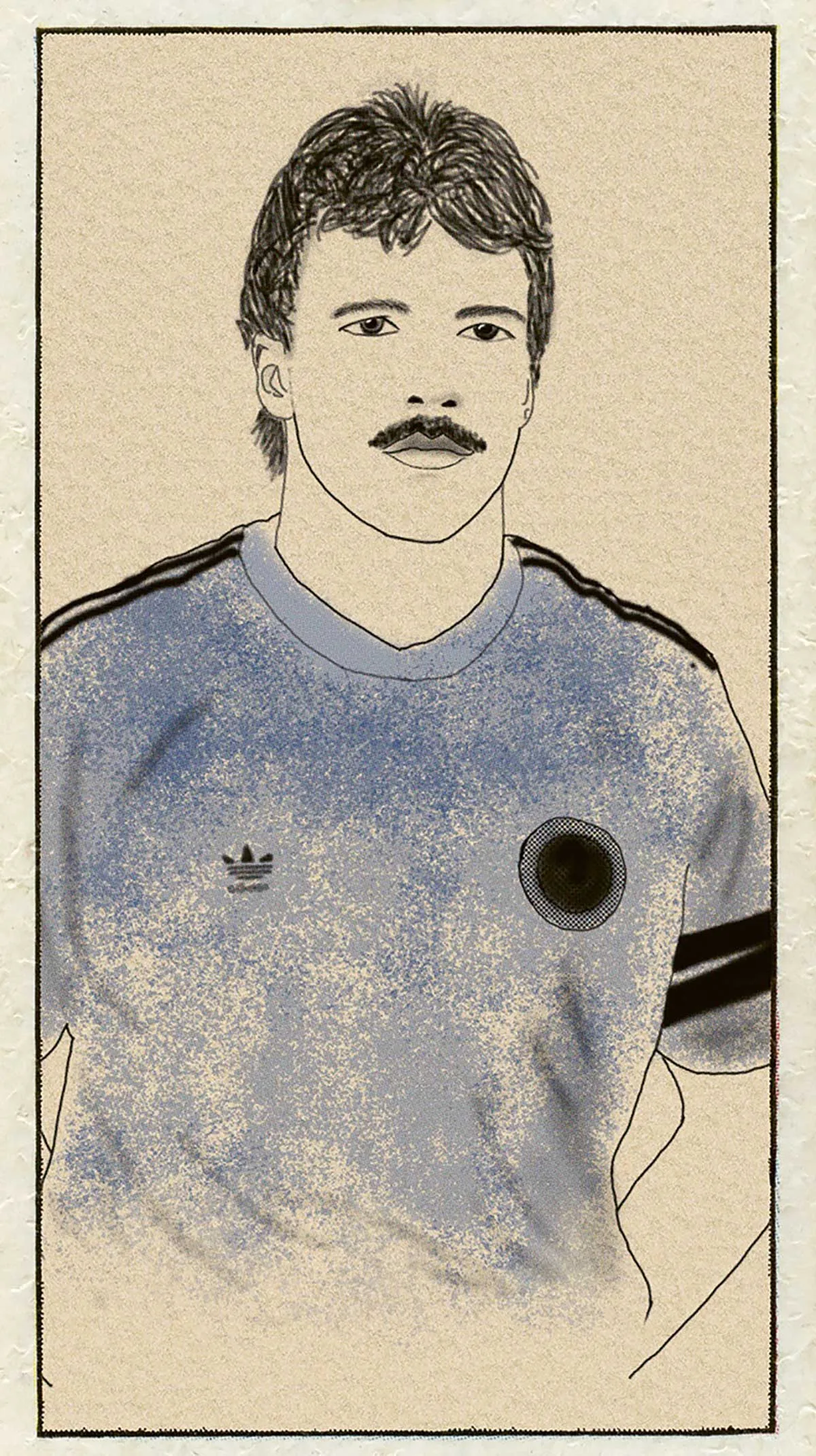

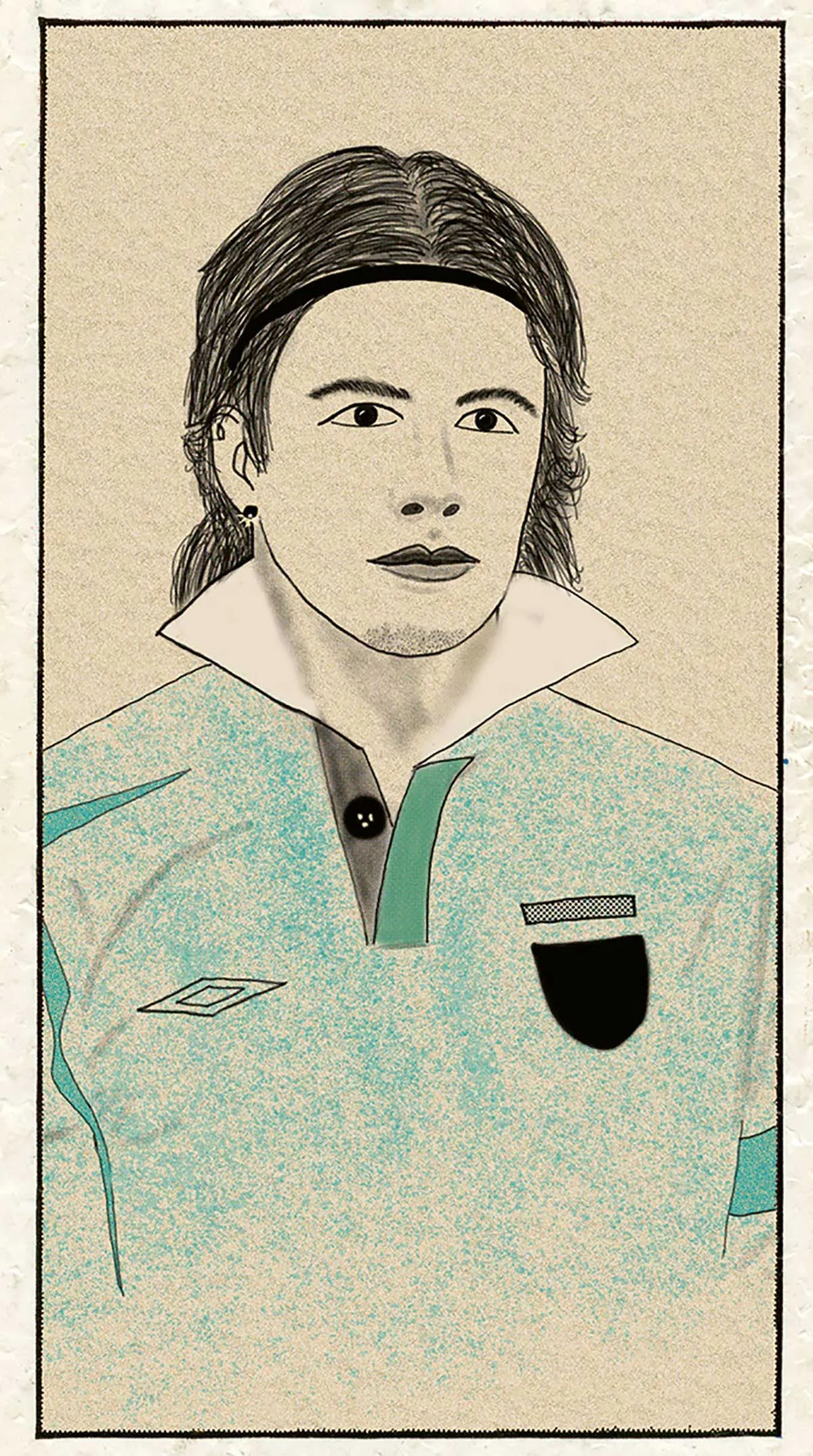

From fighter to model

In the 1980s the footballer was a fighter; a decade later, he was a sporty pop star, and now he’s a model. Nowhere is the change in the image of masculinity more apparent than on the football pitch.

The fighter: 1980s

The pop star: 1990s

The model: 2000s onwards