Types of men in football

The image of masculinity has changed constantly over the past few decades. Nowhere is this more apparent than on the football pitch. A look back at the stadiums of the past.

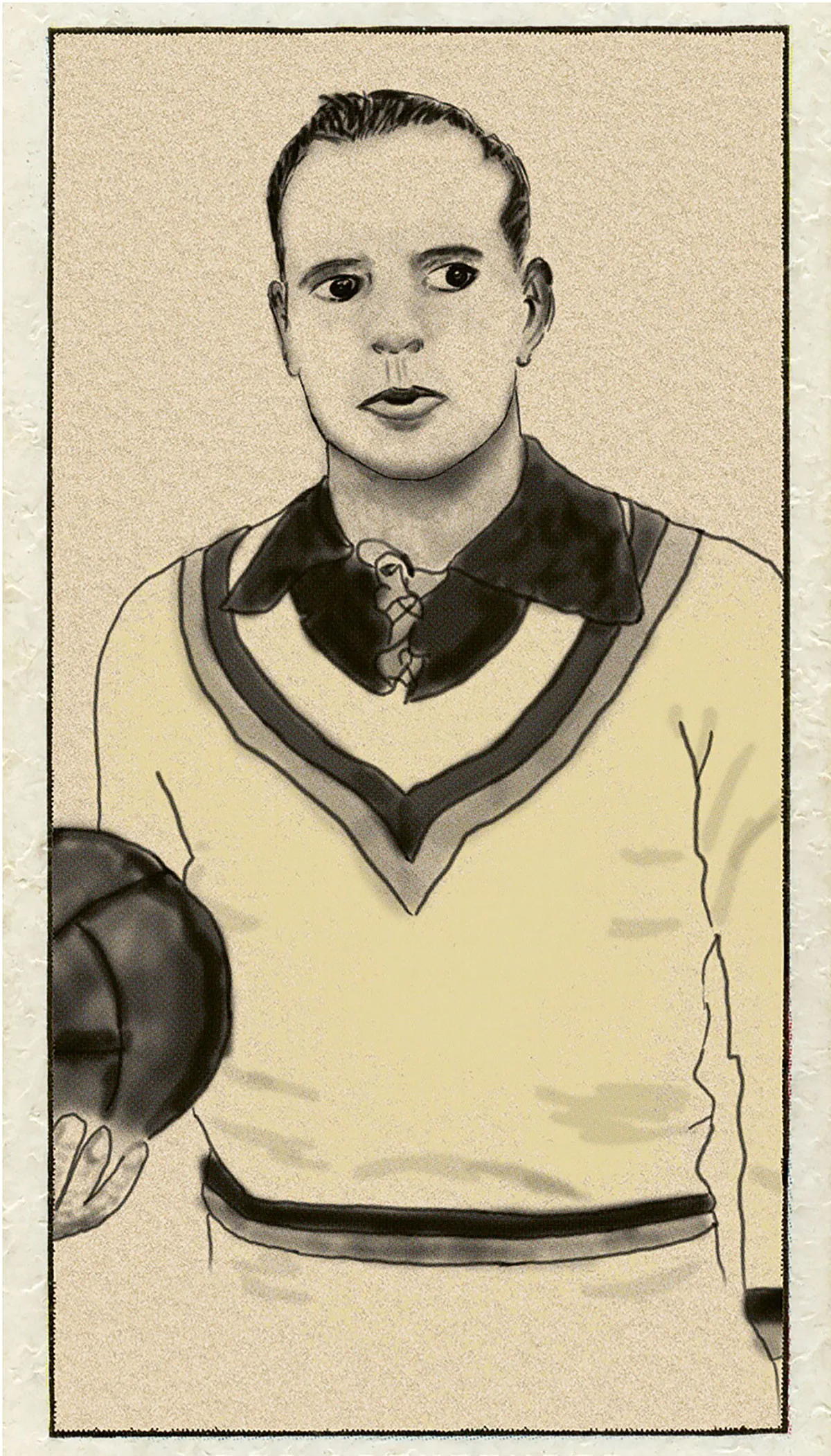

The adventurer: 1930s to 1950s

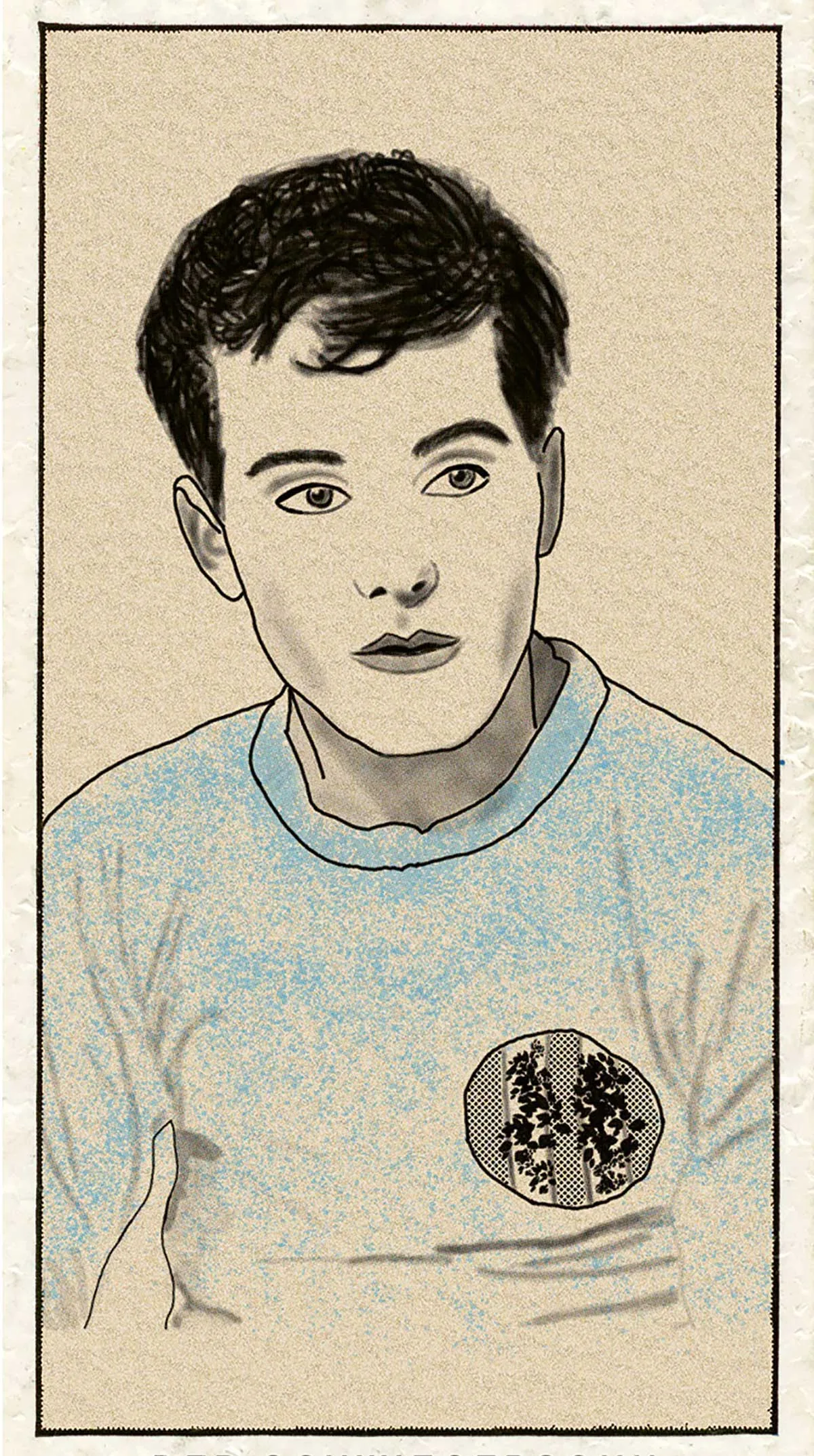

The son-in-law: 1960s

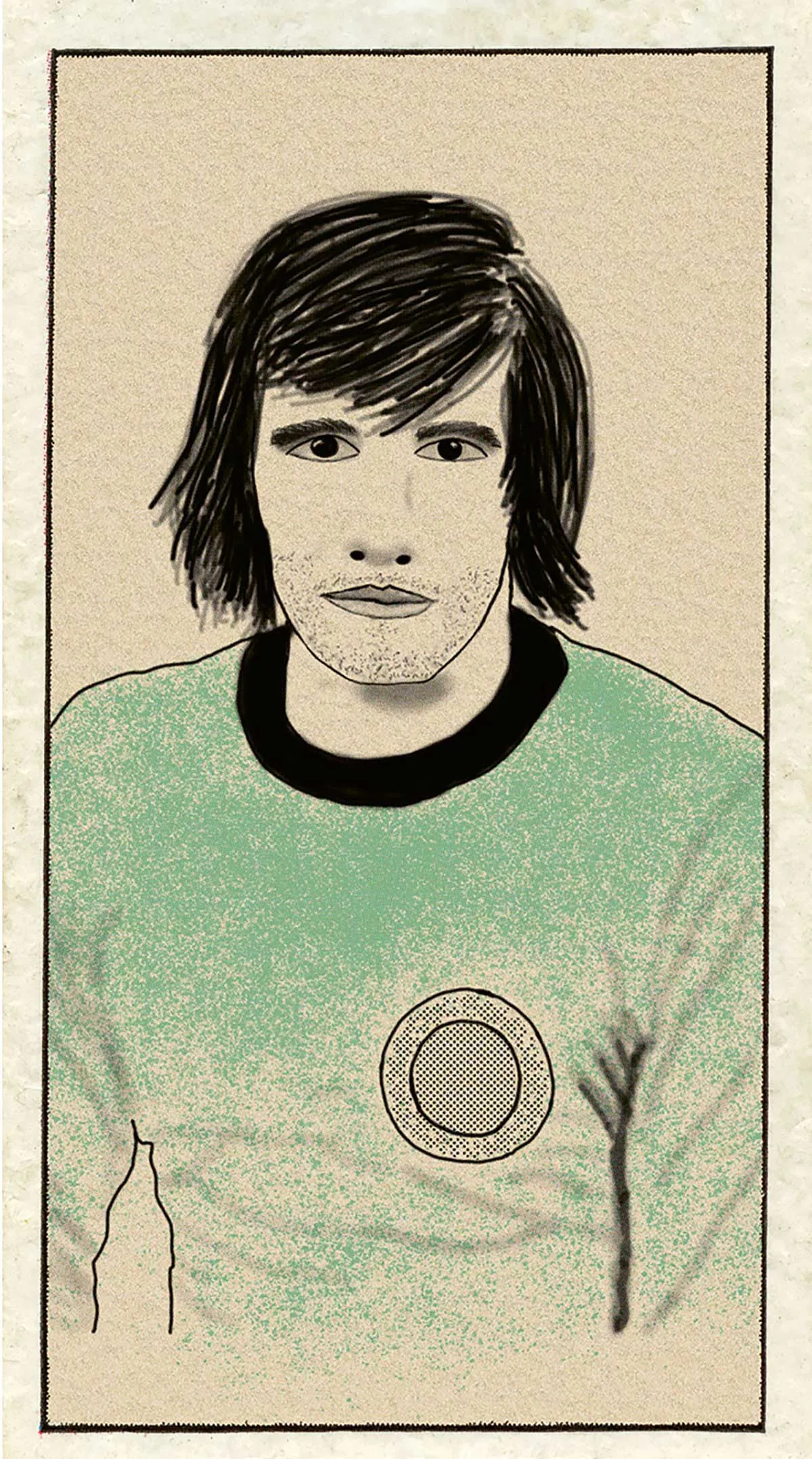

The almost-rebel: 1970s