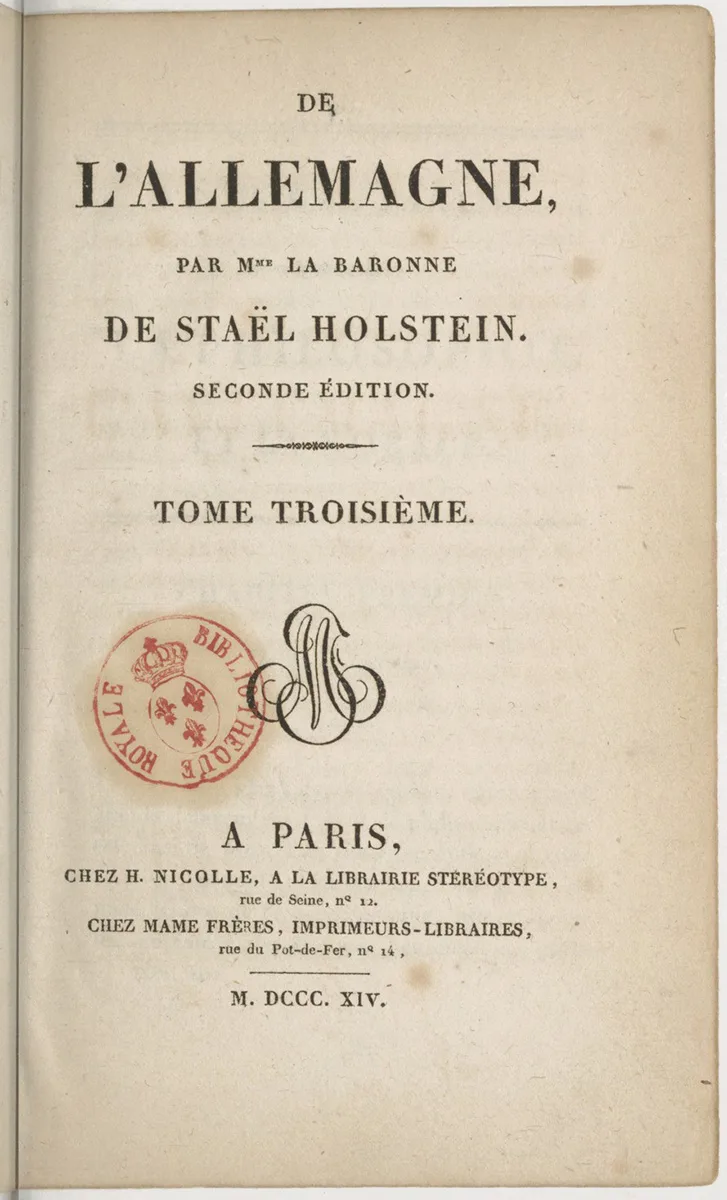

Madame de Staël – Enemy of Napoleon

Germaine de Staël was a Swiss author and thinker during the French Revolution. Even Napoleon feared the strong and well-connected personality and banished her from Paris.

Early Life

There were three great powers struggling against Napoleon for the soul of Europe — England, Russia, and Madame de Staël.

French Revolution and Napoleon

The greatest happiness is to transform one's feelings into action.

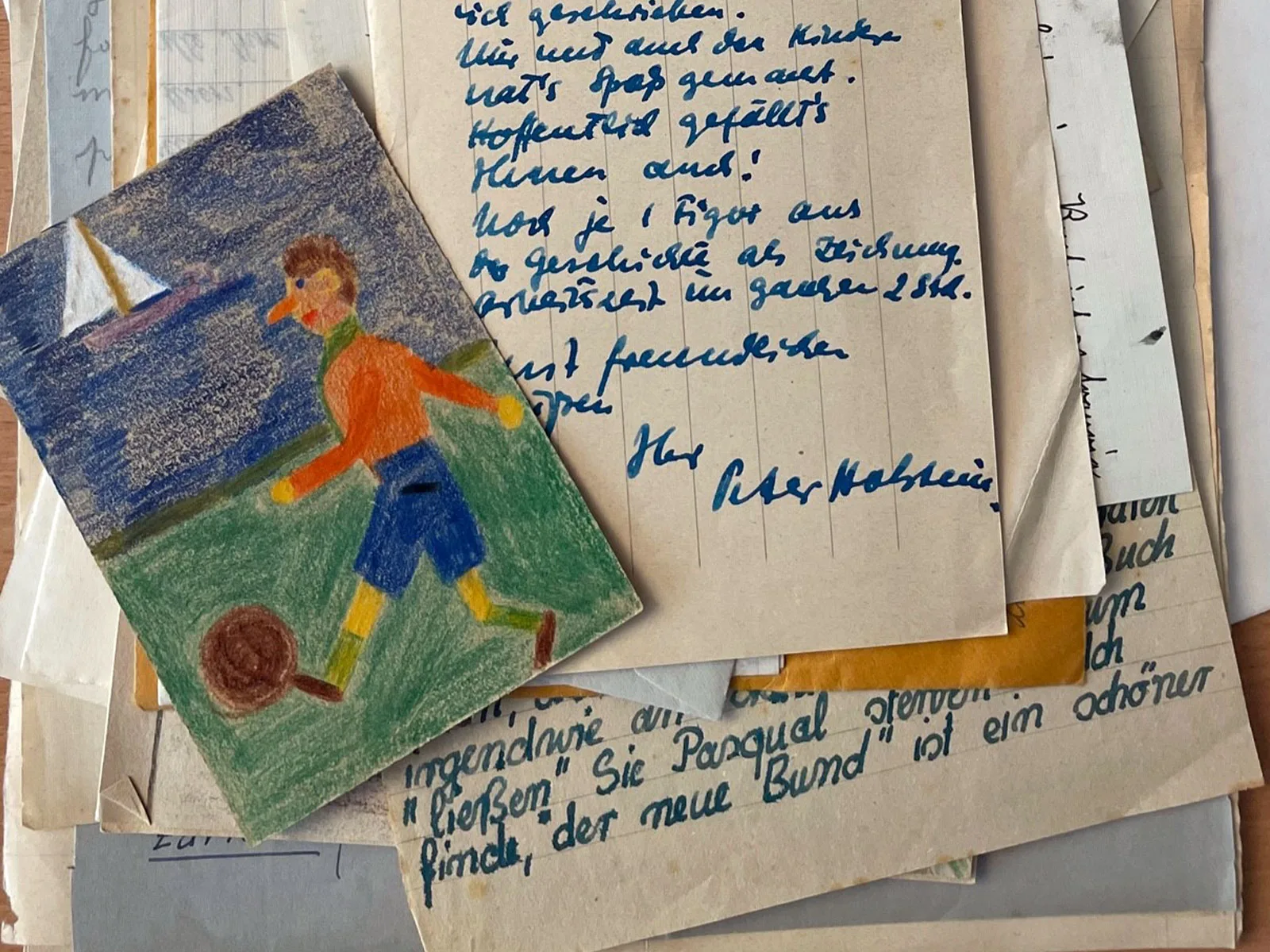

Second Exile and Legacy