99 years of radio in Switzerland

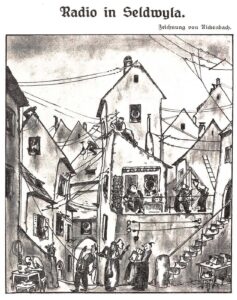

99 years ago, one of Switzerland’s earliest known radio broadcasts hit the airwaves. In Lausanne, the ‘Champ-de-l’Air’ aircraft radio station broadcast a vocal performance live from the studio. Swiss radio was born. In the 1920s, listening to the radio was an adventure and a thrilling journey into uncharted territory. A look back at the pioneering age of radio.

Radio in the 1920s. YouTube / The1920sChannel

Early radio reception

This blog post was originally published on the blog of the Museum of Communication.