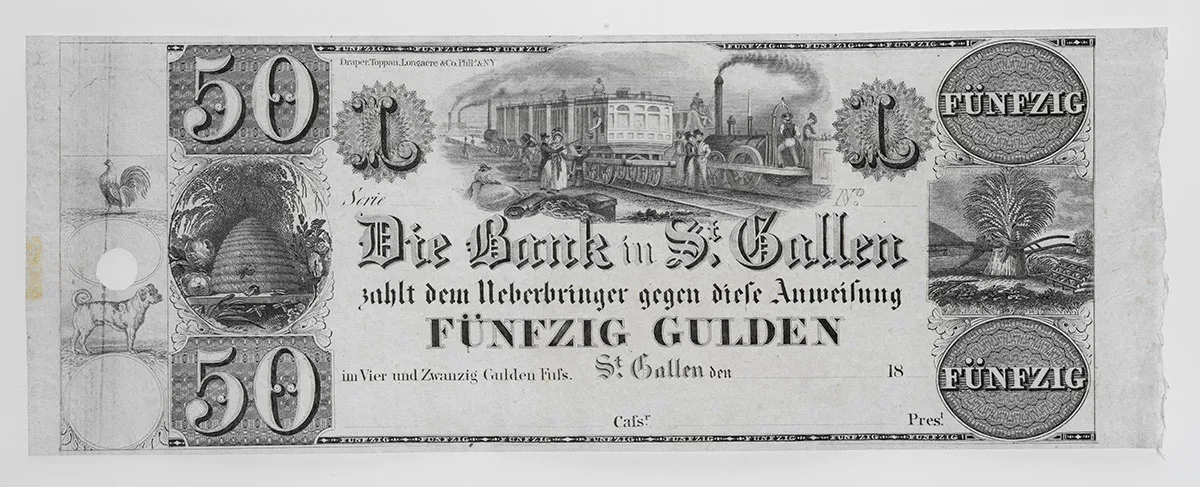

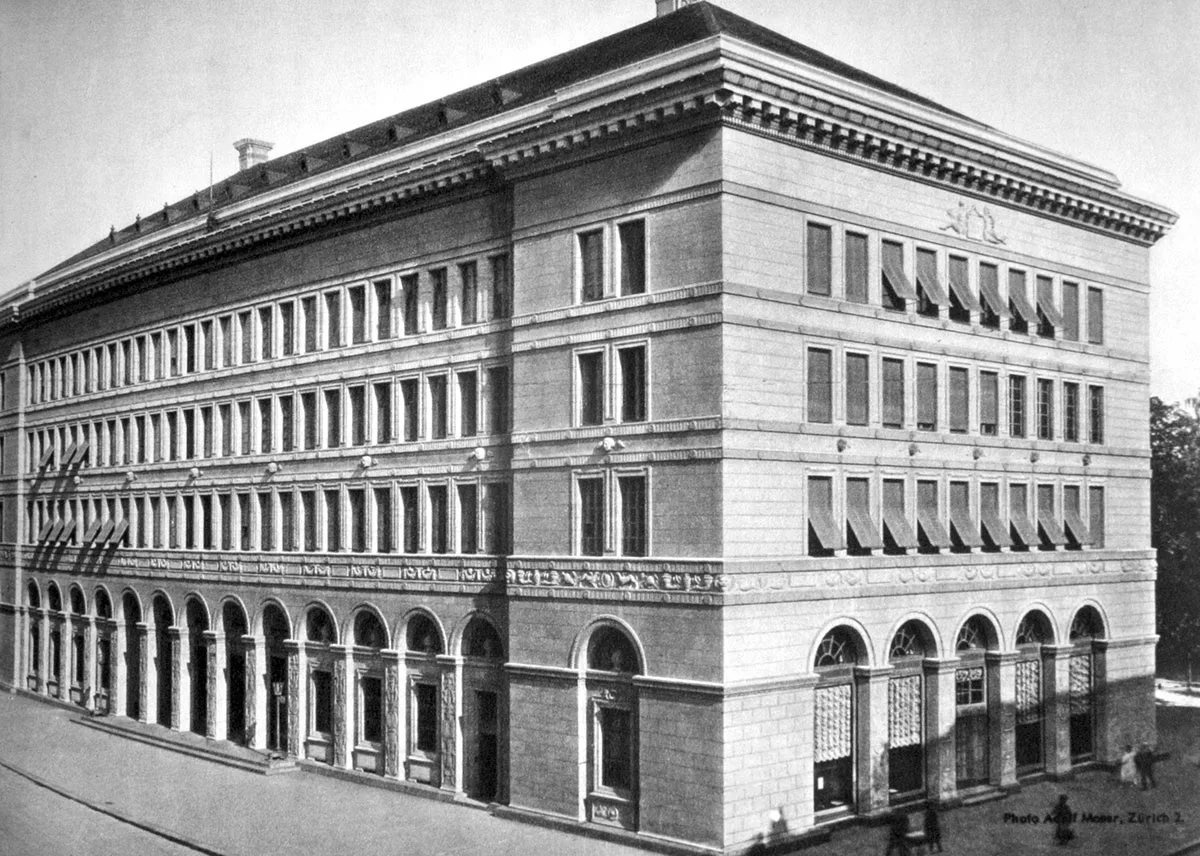

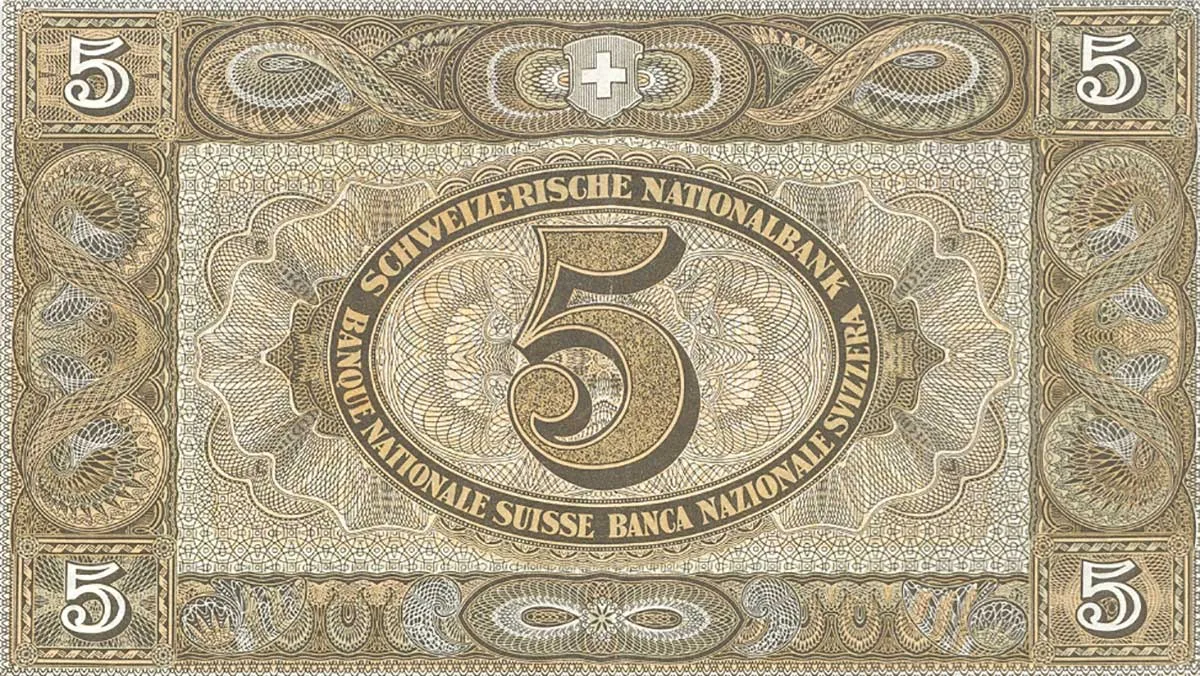

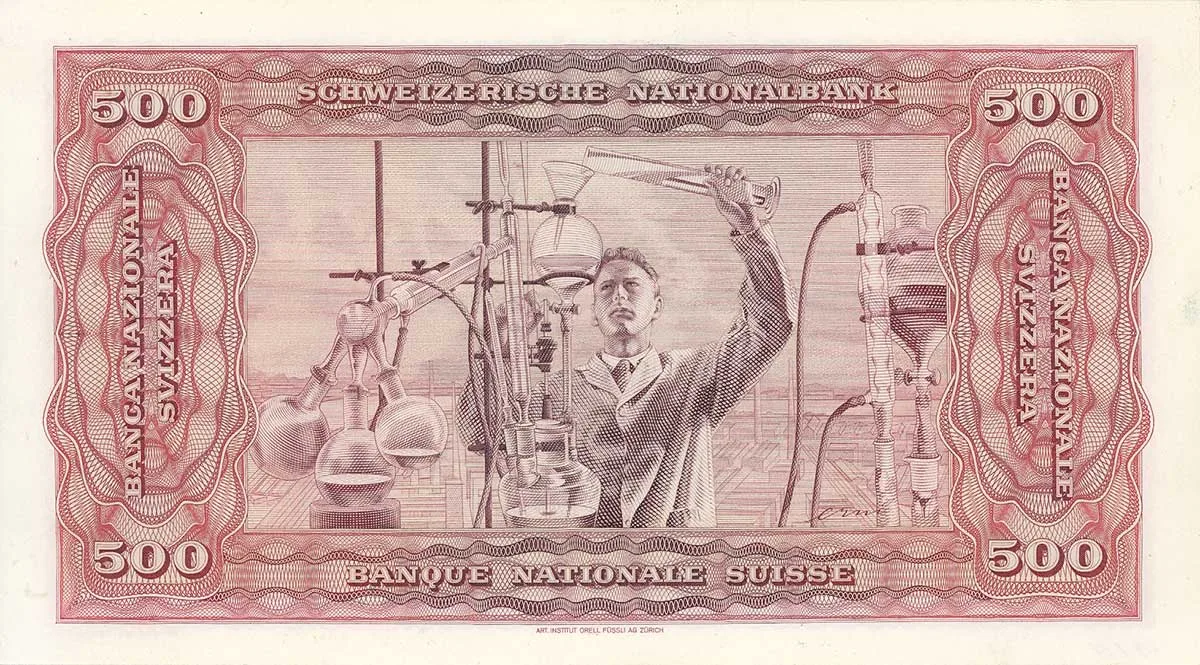

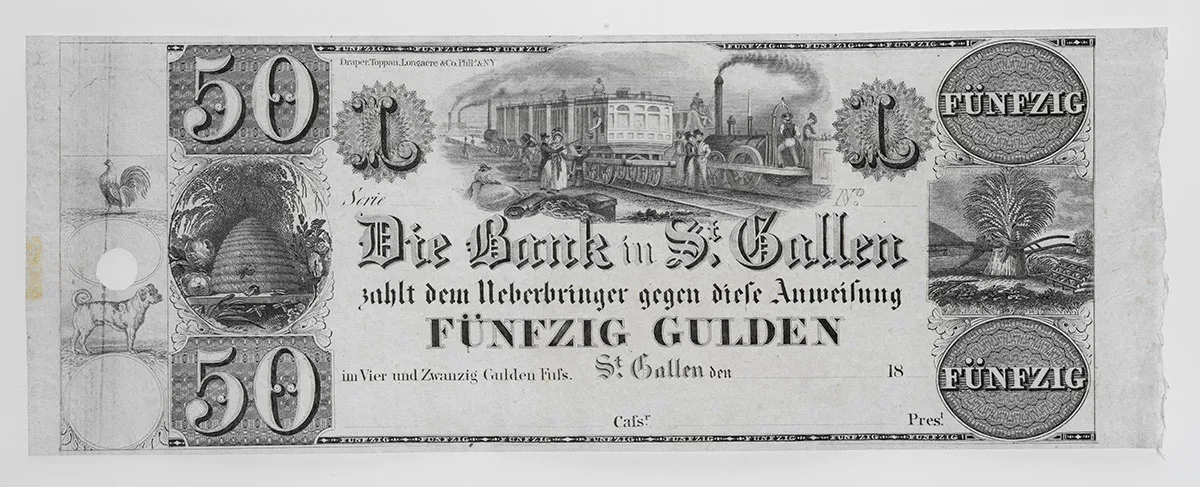

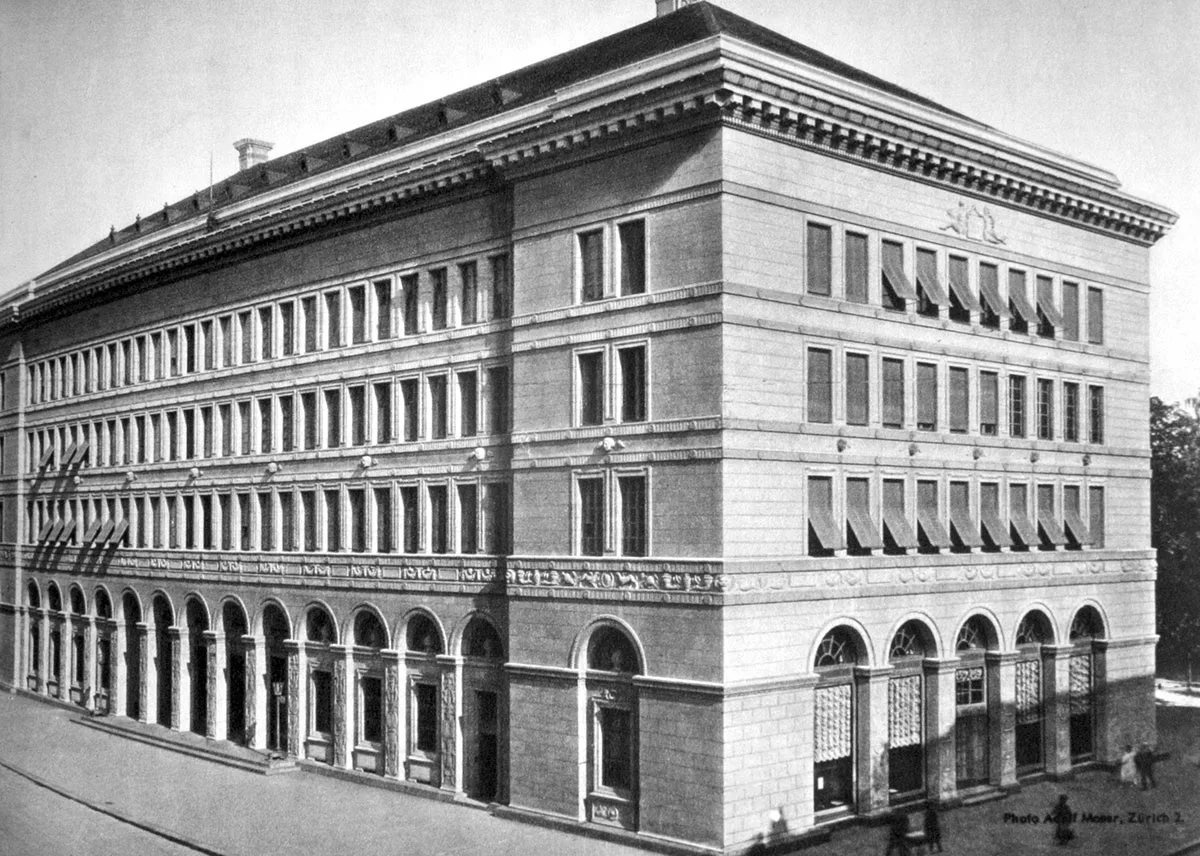

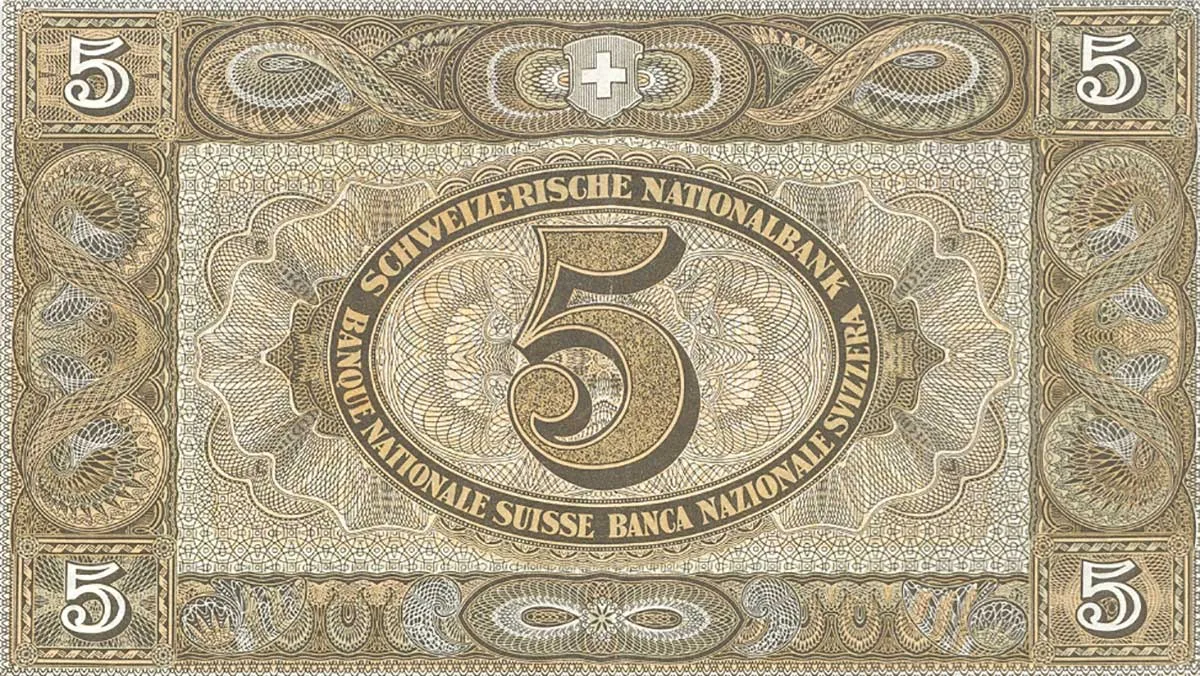

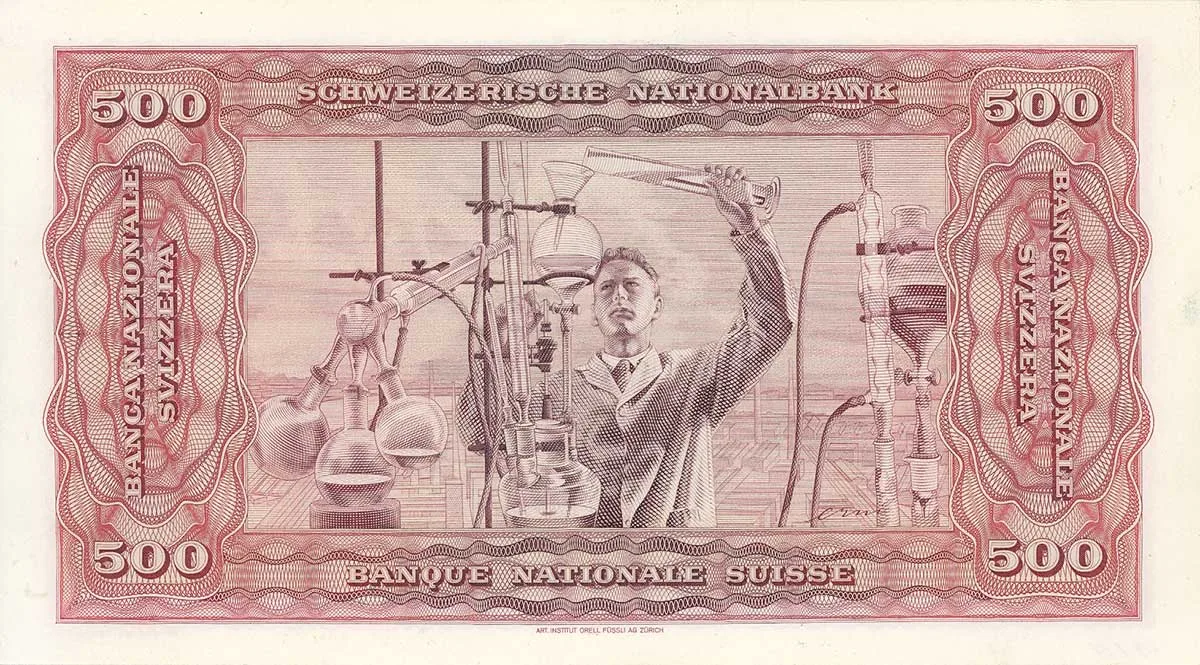

Banknotes for emergencies

What do you do when counterfeiters or a hostile power flood the country with counterfeit money? The contingency plan formulated by the Swiss National Bank: reserve notes.

What do you do when counterfeiters or a hostile power flood the country with counterfeit money? The contingency plan formulated by the Swiss National Bank: reserve notes.