The Bärschwil triple murder

A bloody slaying in Bärschwil in Solothurn laid bare the global scars left by colonial violence in the late 19th century.

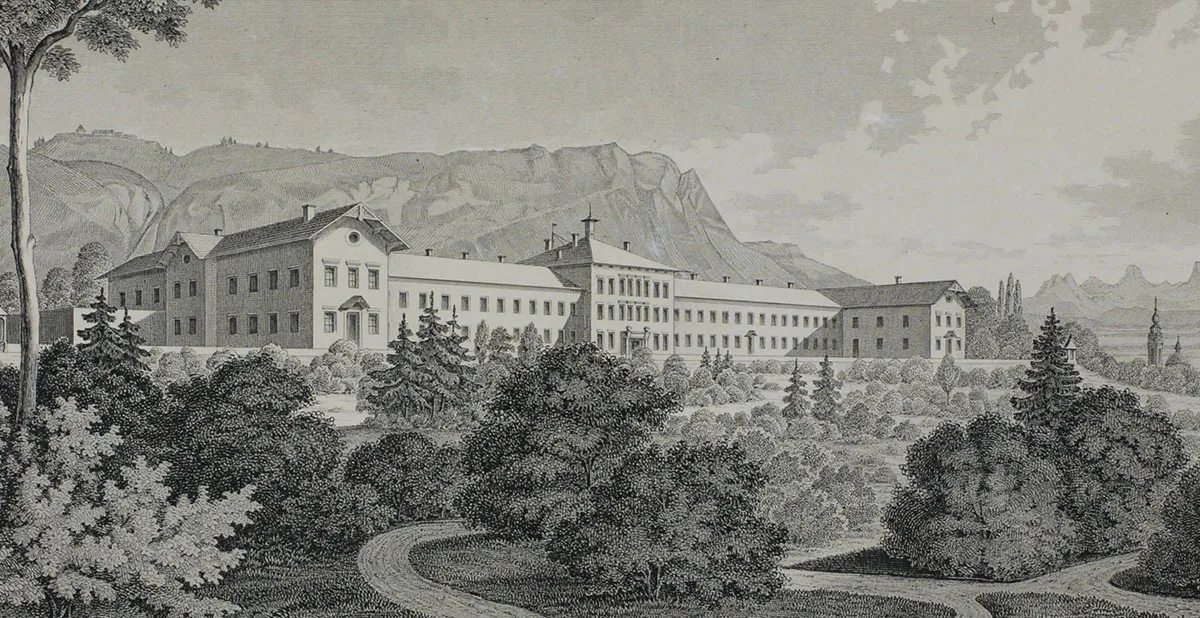

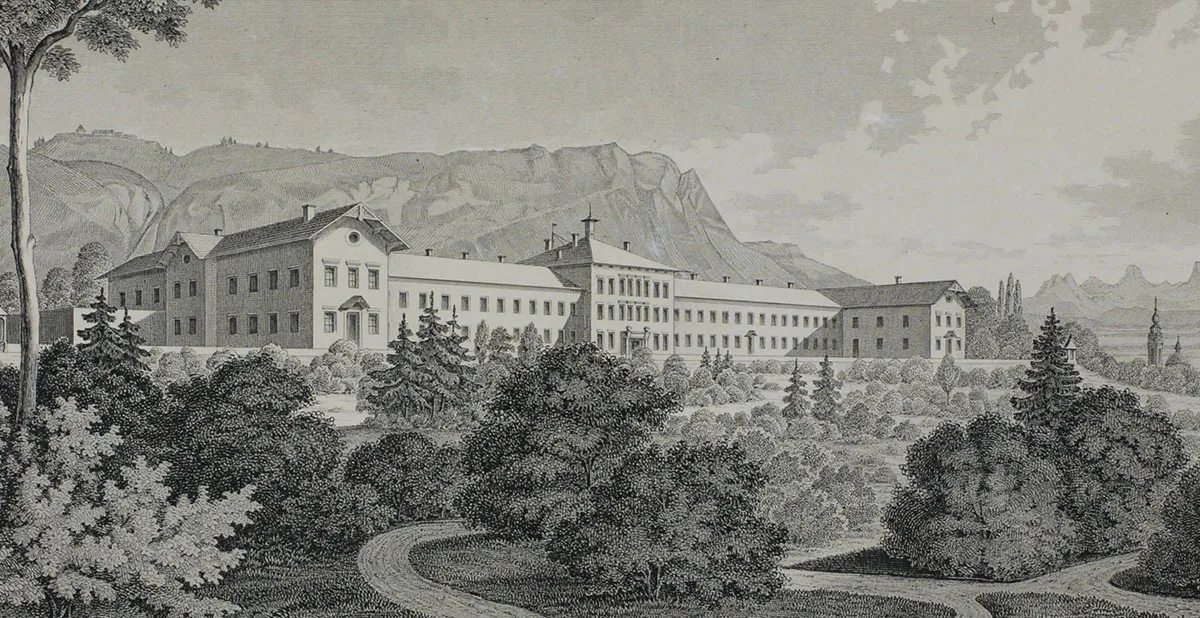

Colonial war in Aceh

Swiss fighters at the front

War and trauma

A bloody slaying in Bärschwil in Solothurn laid bare the global scars left by colonial violence in the late 19th century.