Murder on Säntis

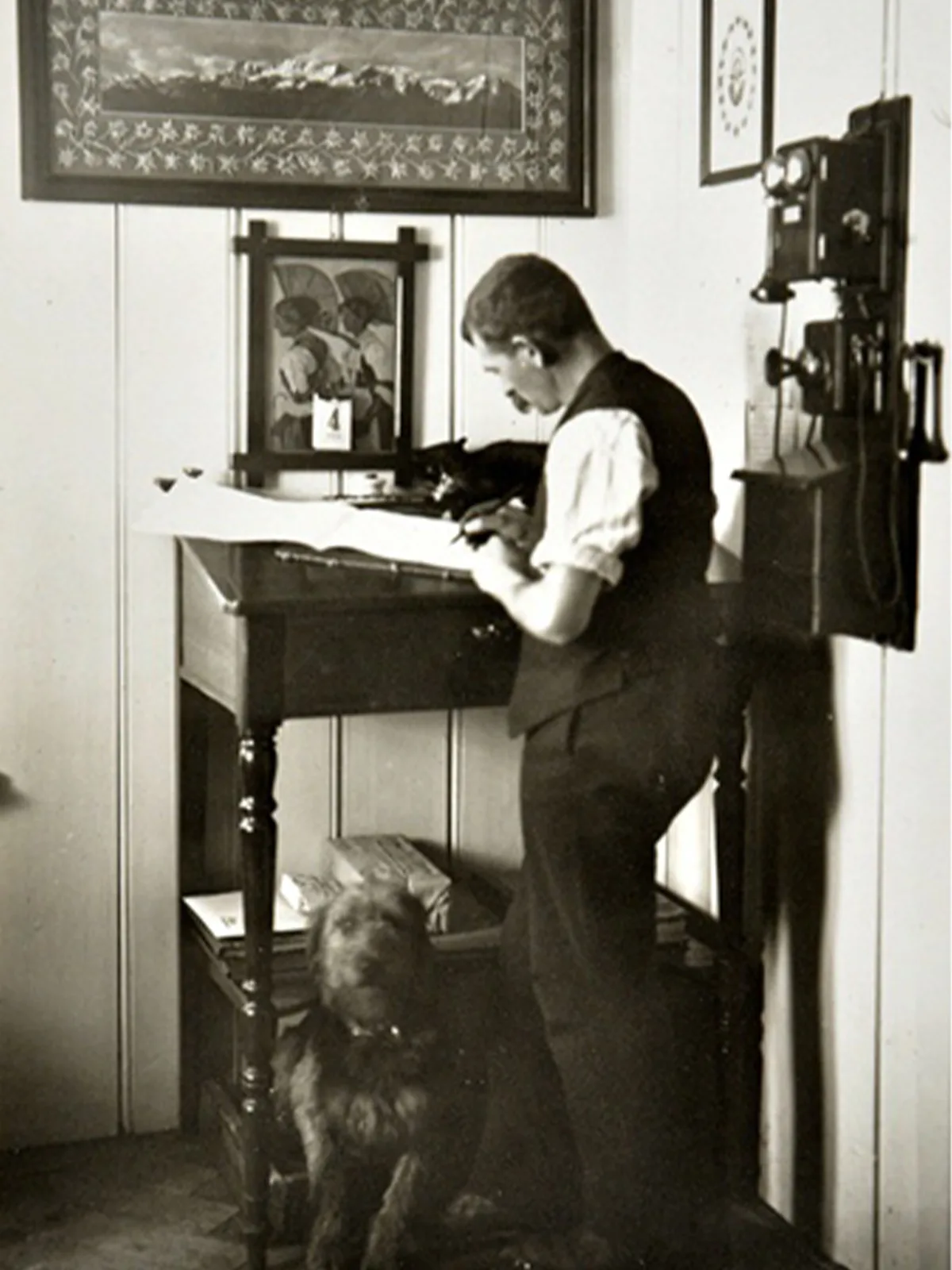

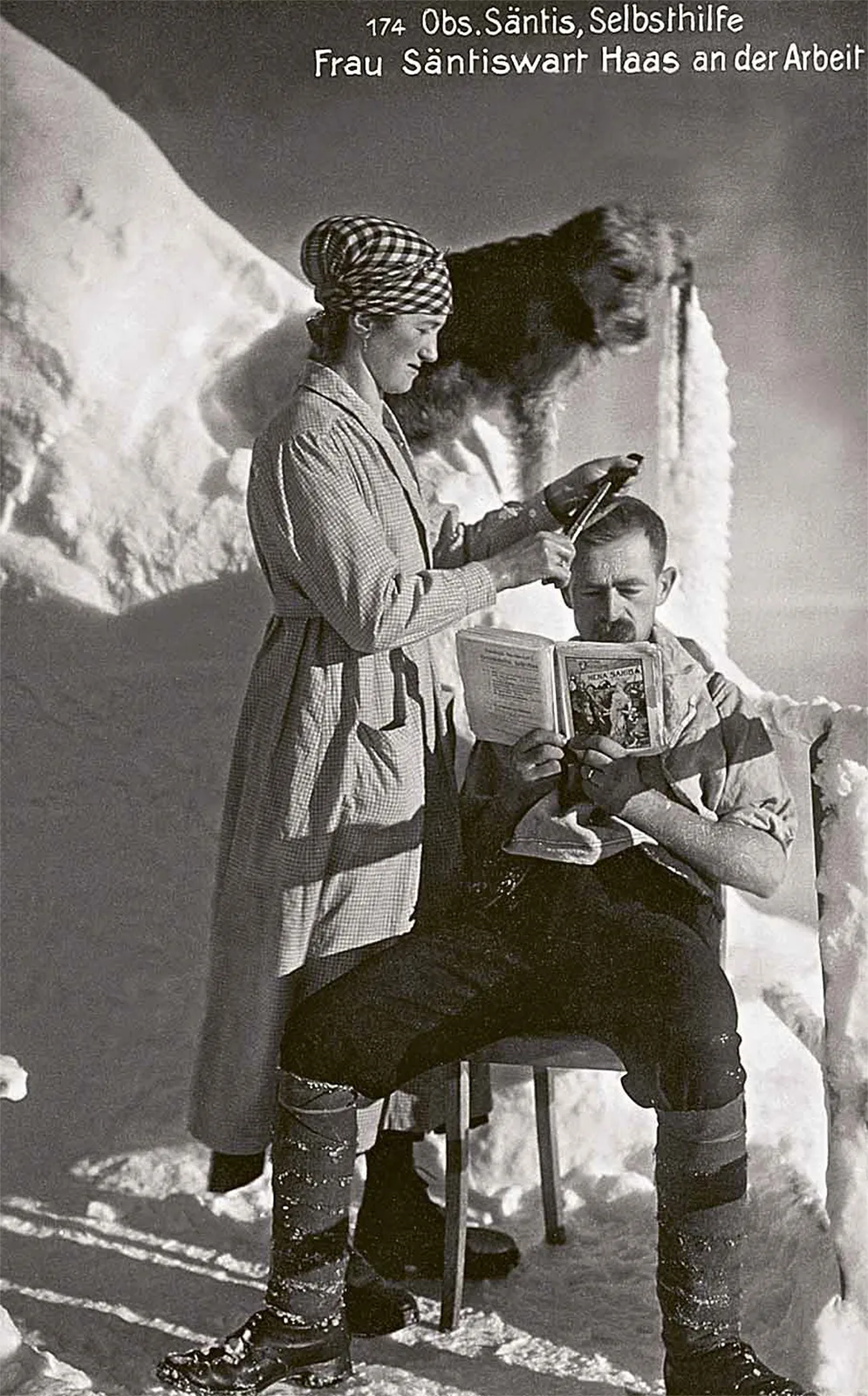

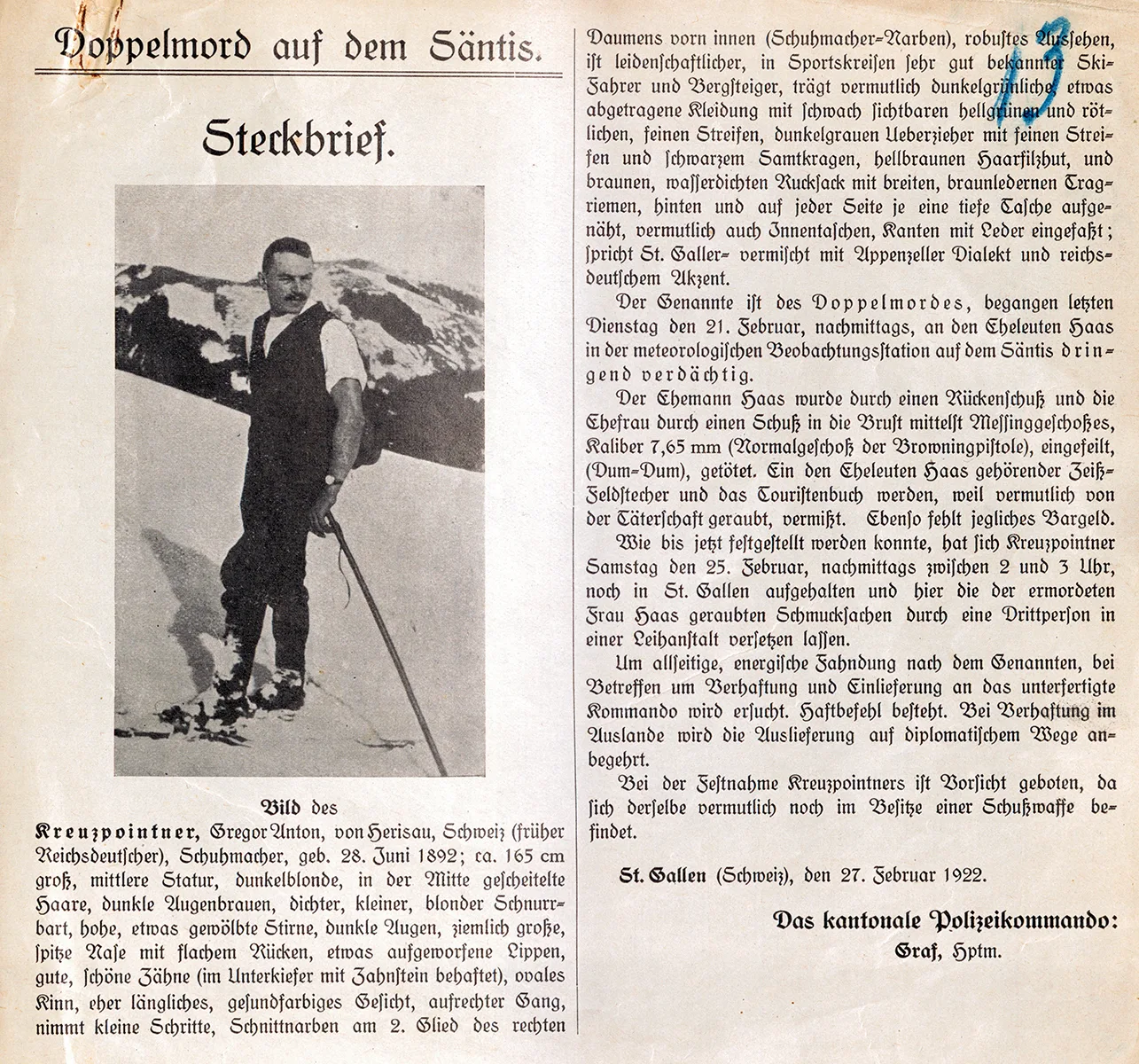

In February 1922, the operator of the Säntis weather station and his wife became victims of a crime. New findings are shining a light on the dark story behind this crime that caused widespread consternation.

The victims and perpetrator knew each other

To die for…

Macabre back and forth over the corpses

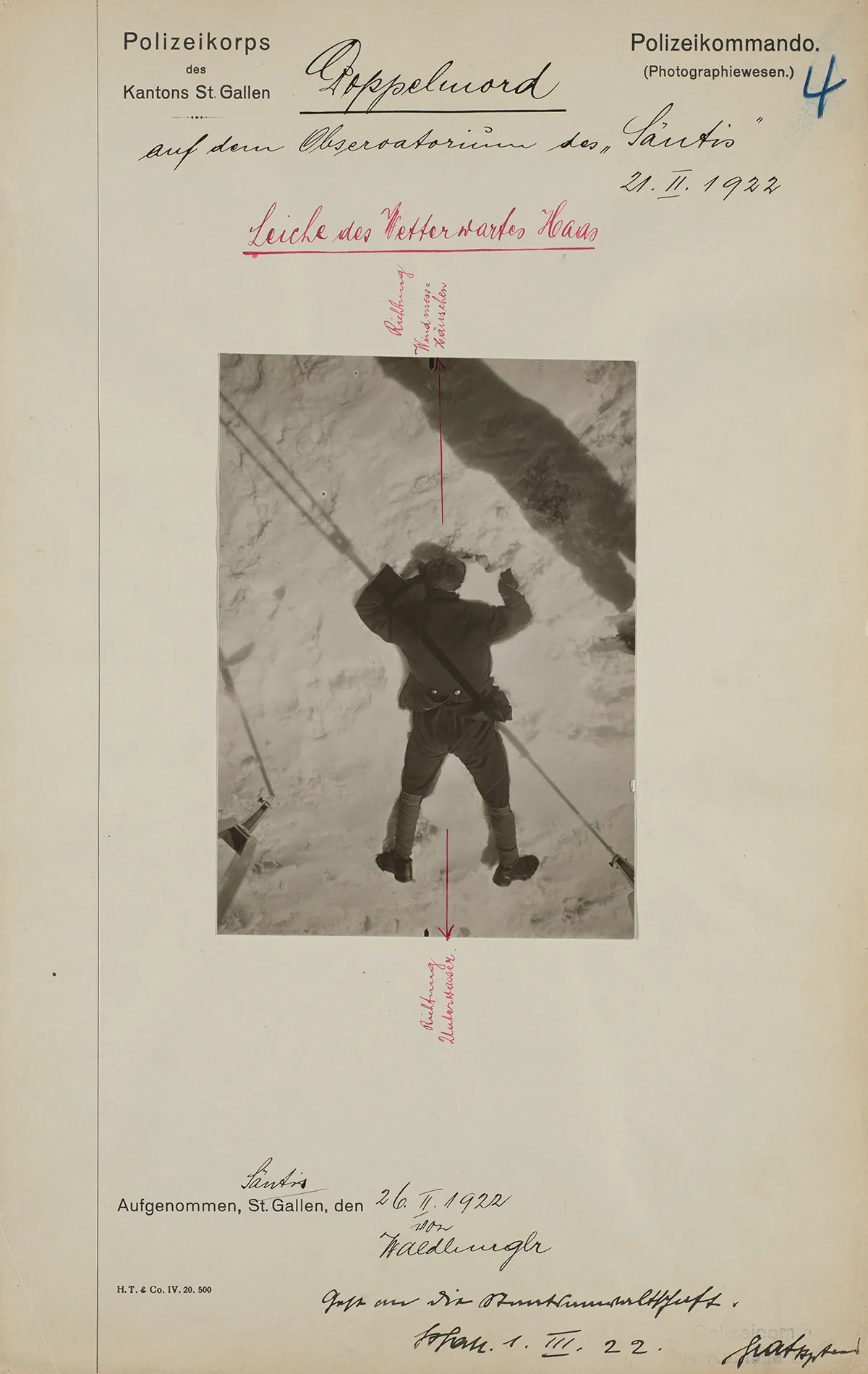

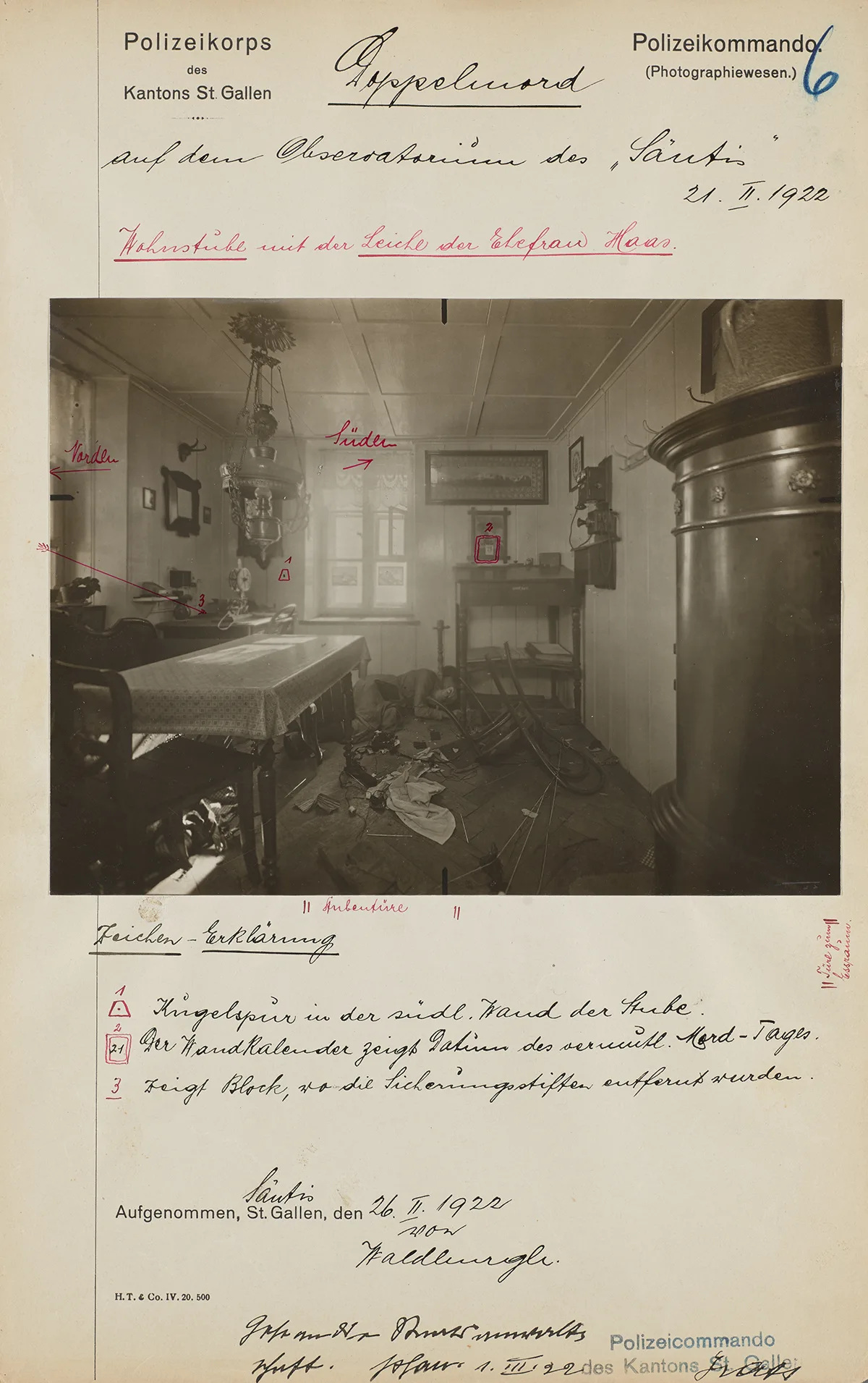

At the time, there was disagreement between the experts over cantonal responsibility for the crime: the borders of the Canton of St Gallen and the two half-cantons of Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Appenzell Innerrhoden meet at the summit of Säntis. The body of Magdalena Haas was clearly found on Innerrhoden territory, since the weather station is situated squarely within this. Heinrich’s body, however, lay in an area for which the border between St Gallen and Innerrhoden was drawn too imprecisely on the map for it to be clearly assigned. For this reason, the police and anatomical investigative work was divided between Innerrhoden and St Gallen.

Kreuzpointner’s body was found in the Ausserrhoden municipality of Urnäsch. Despite this, he was denied a grave in the cemetery there because this would have led to “the cemetery being desecrated”. Herisau, where he was a citizen, and the city of St Gallen, where he was last registered, were likewise unwilling to have the evildoer on their soil or land. In doing so, all three violated the Federal Constitution. According to this, it is the authorities’ responsibility to ensure that “every deceased person is able to be buried as is fitting”. The corpse was sent to the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Zurich for research purposes. All three municipalities paid for its transport there.

This article appeared in the Bieler Tagblatt. It was published in that newspaper on 19 February 2022 under the title “The view up there is to die for”.