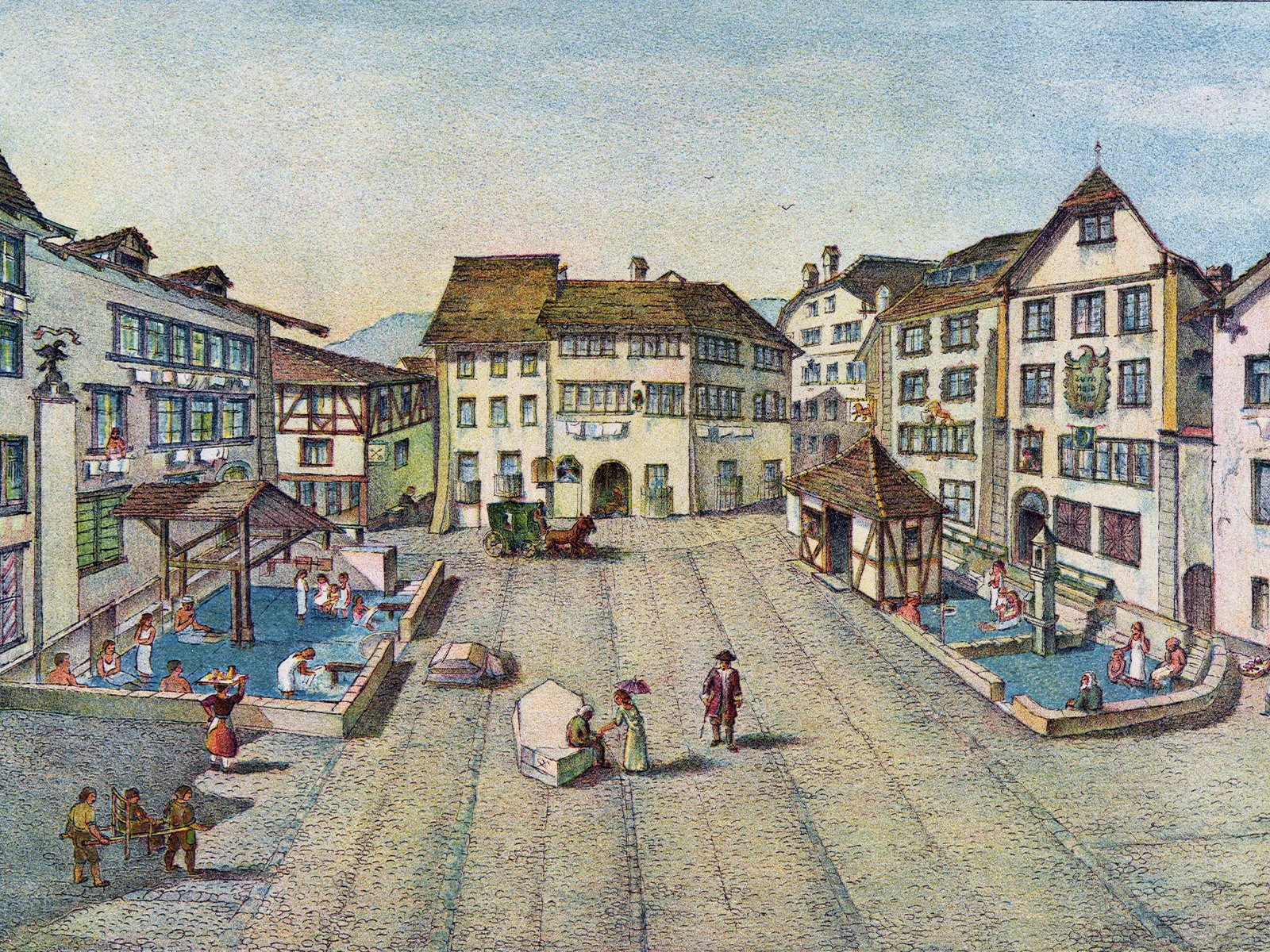

Bathing in the open air

Up to the mid-19th century, the mineral hot baths in Baden im Aargau were known for their open-air thermal pools.

Public welfare and politics under the Romans

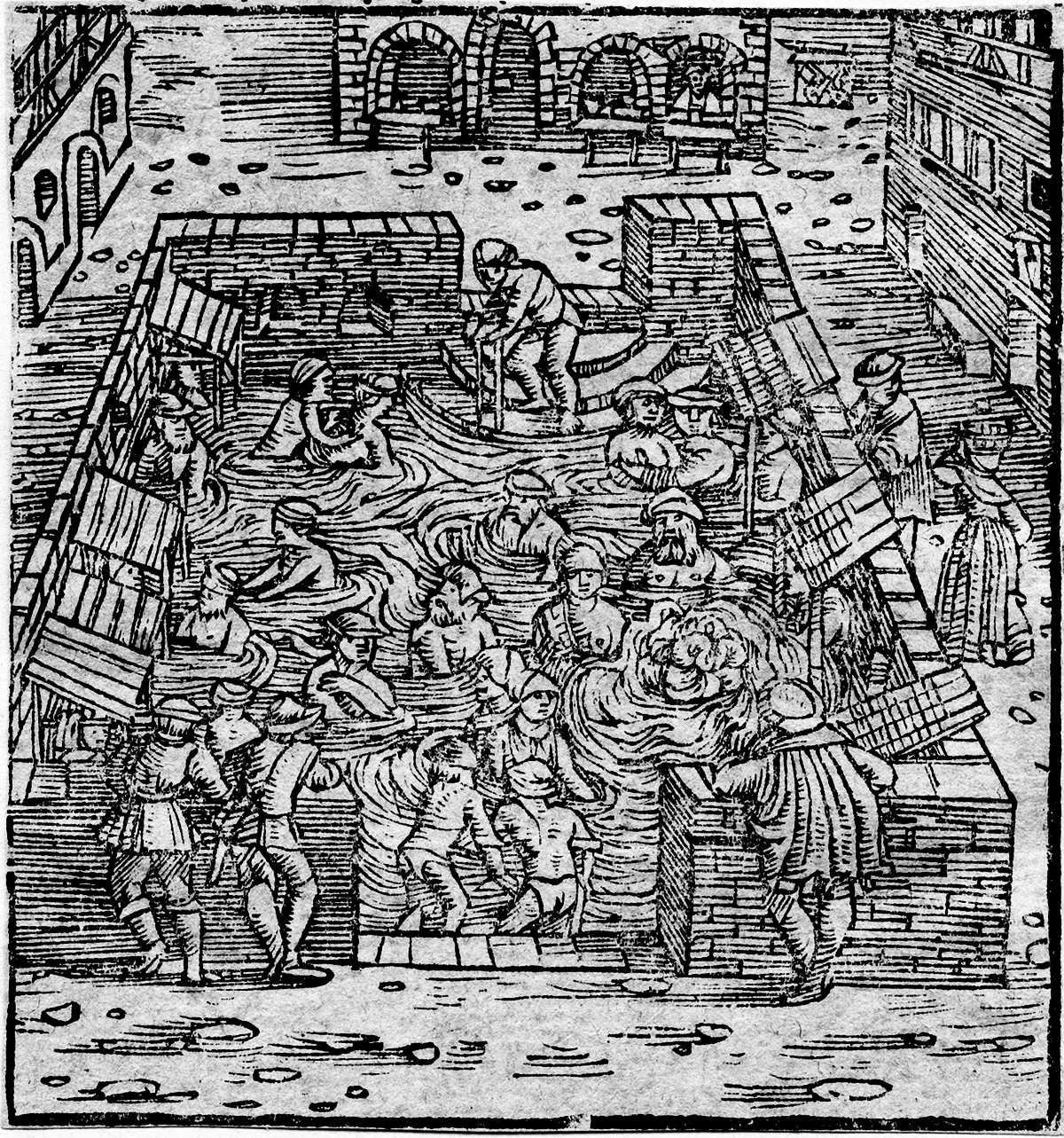

In the Middle Ages: baths for everyone – but separated according to status

St Verenabad and open-air pools

End of the road for the outdoor baths

The tradition is revived