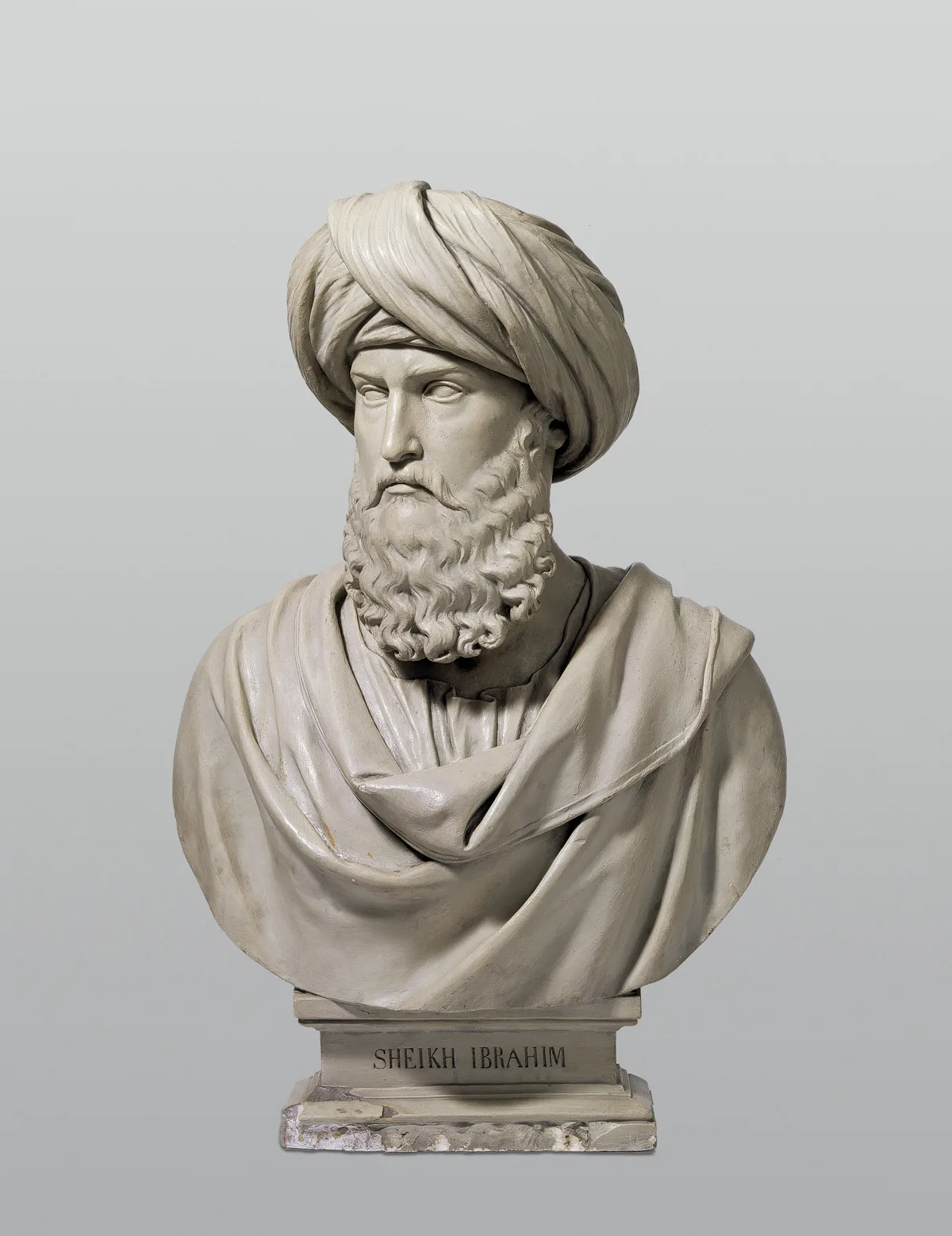

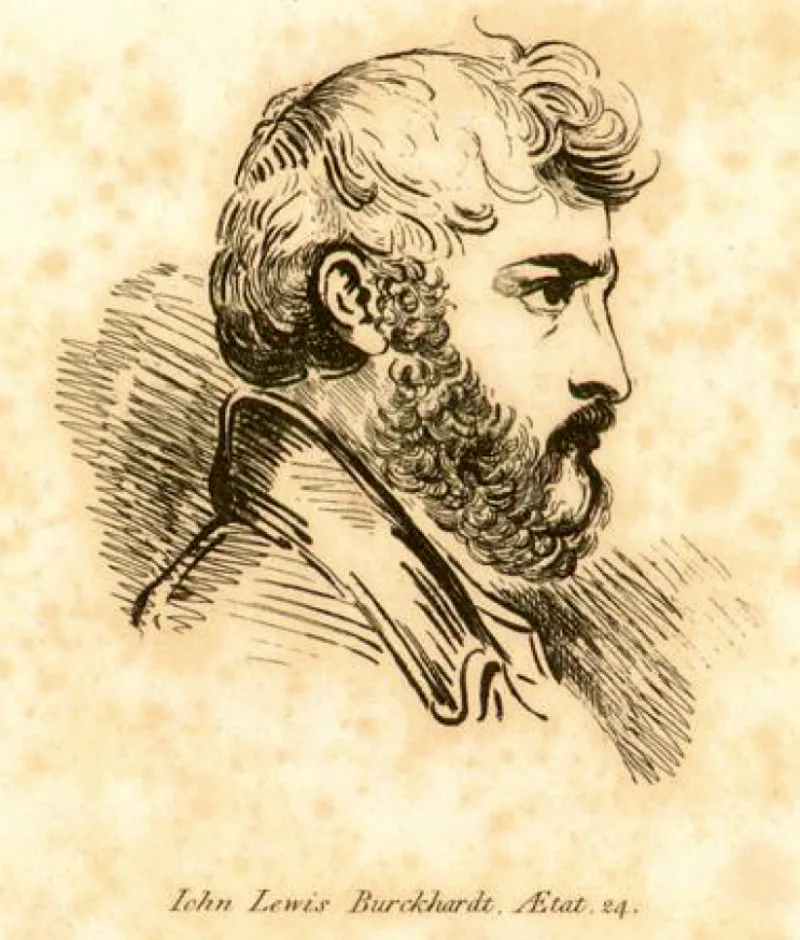

Johan Ludwig Burckhardt: An Intrepid Swiss Explorer

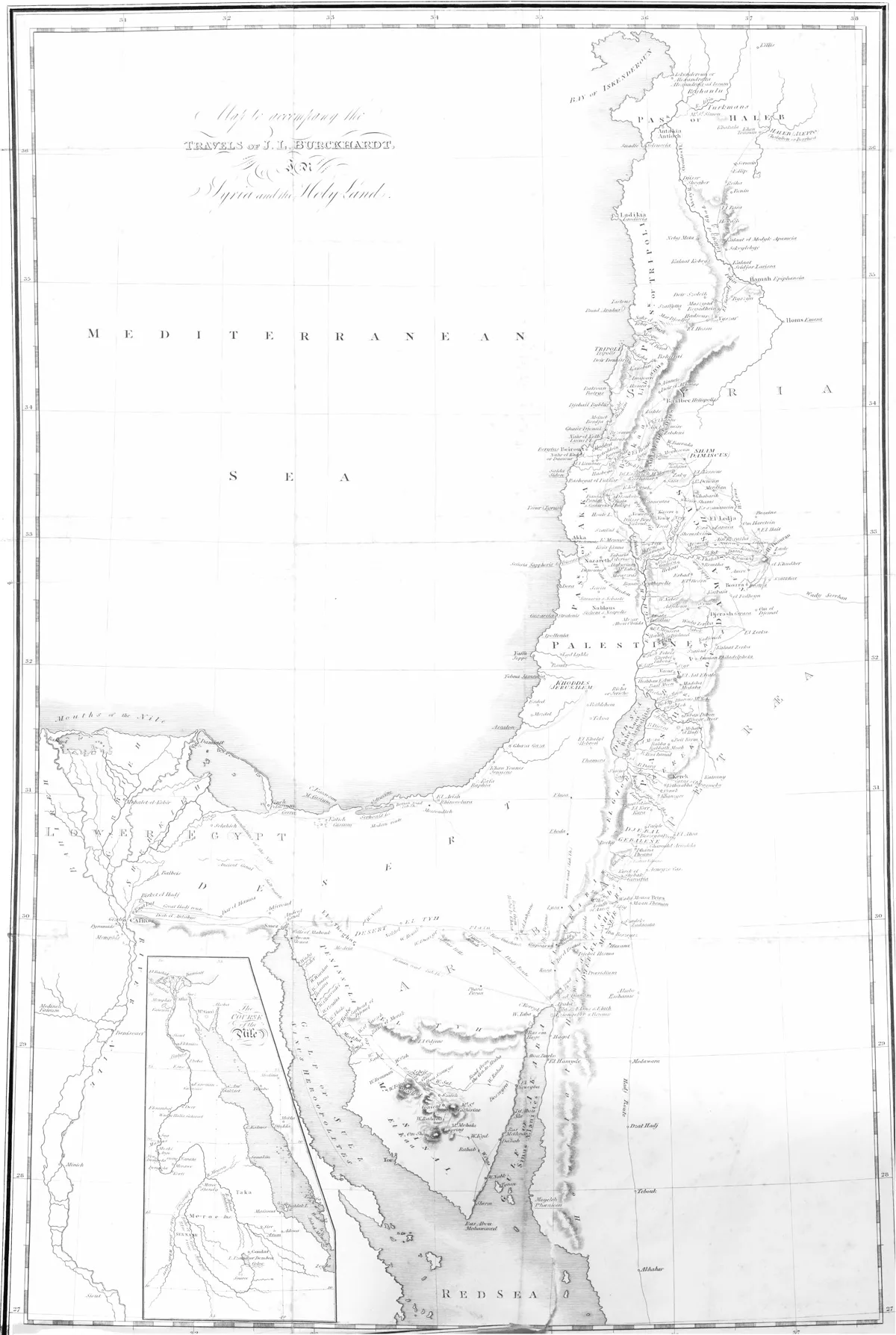

In 1812, the Swiss adventurer and explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784-1817) traversed the ancient Nabataean city of Petra. He was the first European to set his eyes upon the ruins since the time of the Crusades. His life is a curious story of research and unexpected high adventure.

Journey to the Levant

Burckhardt’s Discovery of Petra

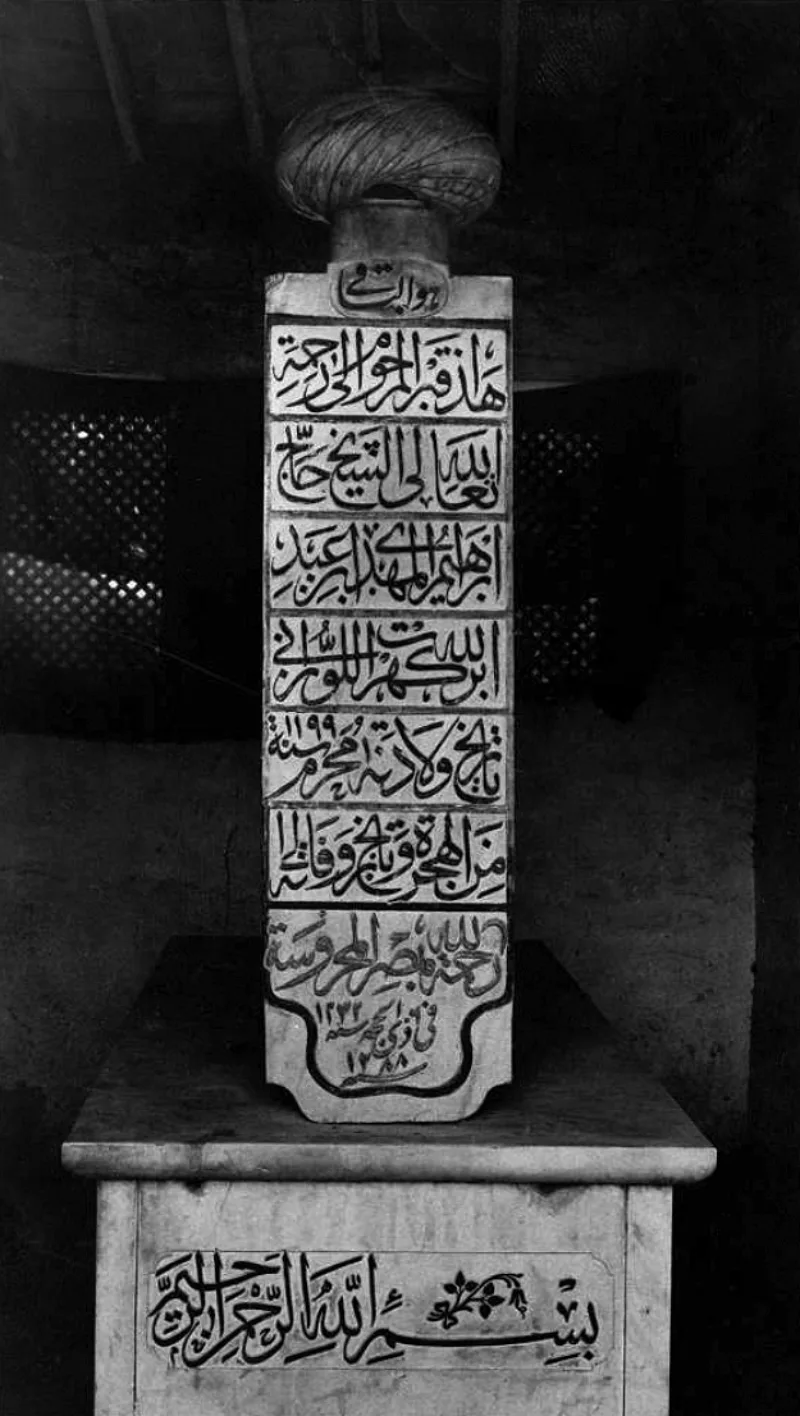

Further Expeditions

An Important Legacy