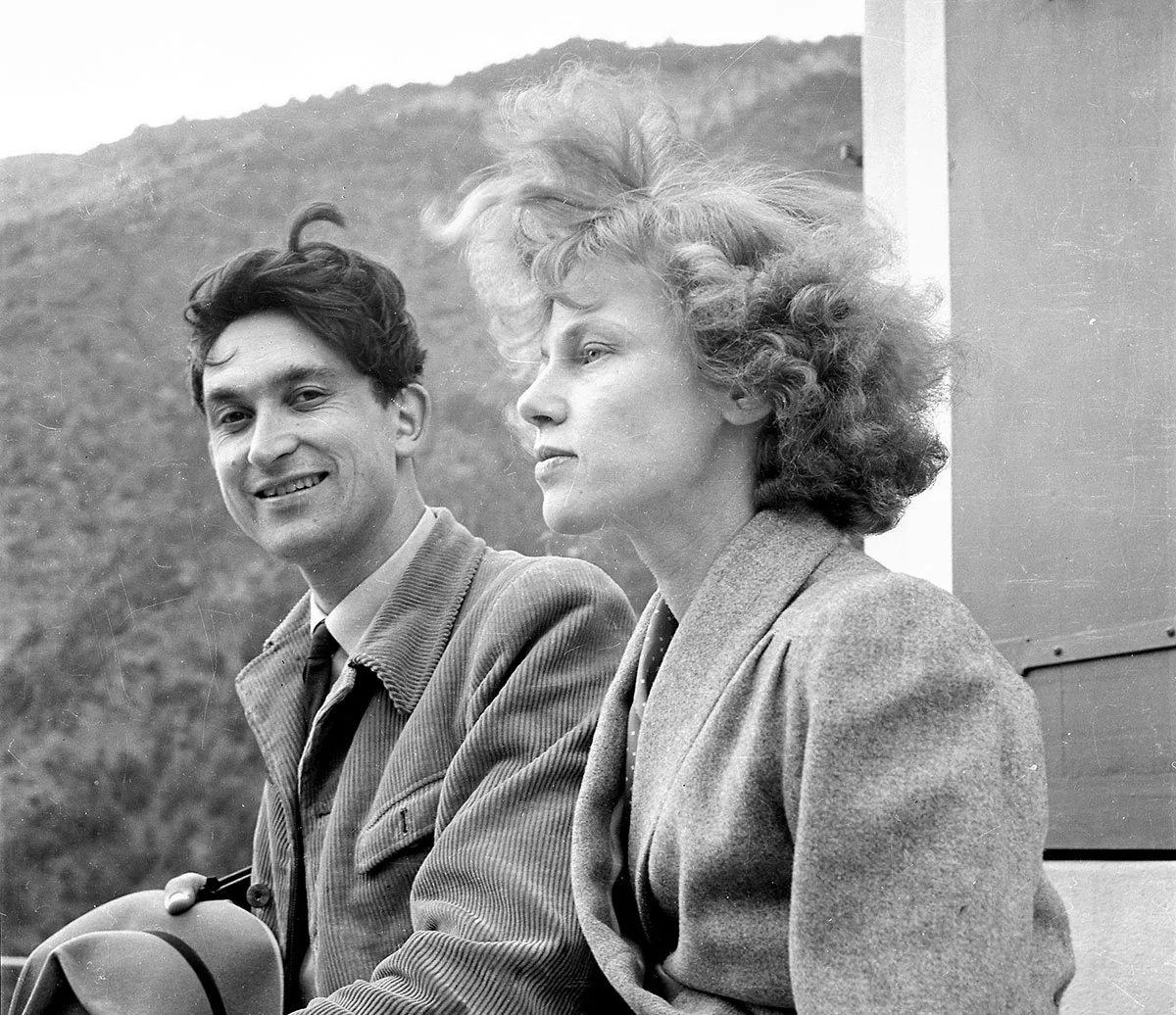

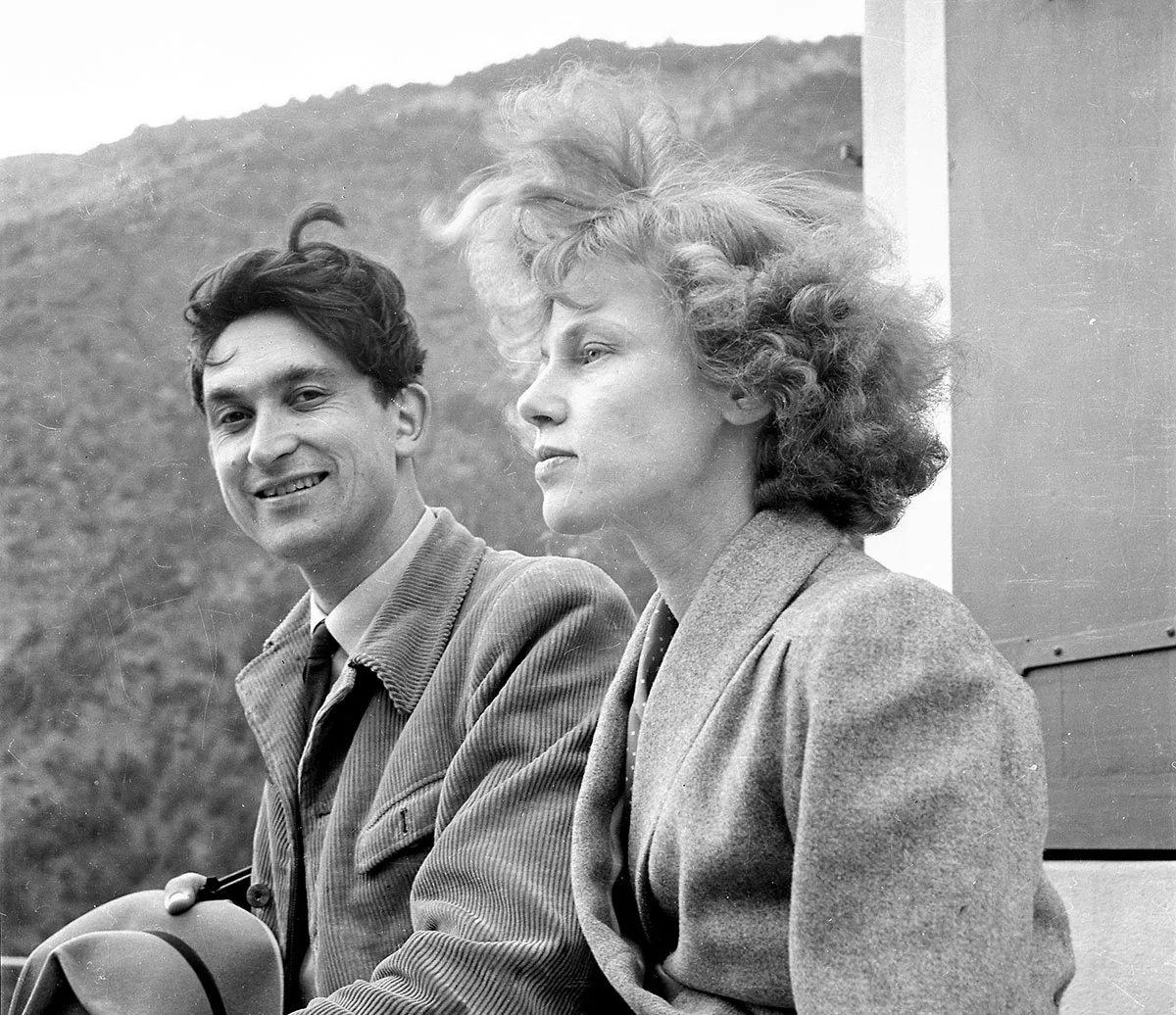

One woman's intrepid trip to the Bosphorus by Fiat

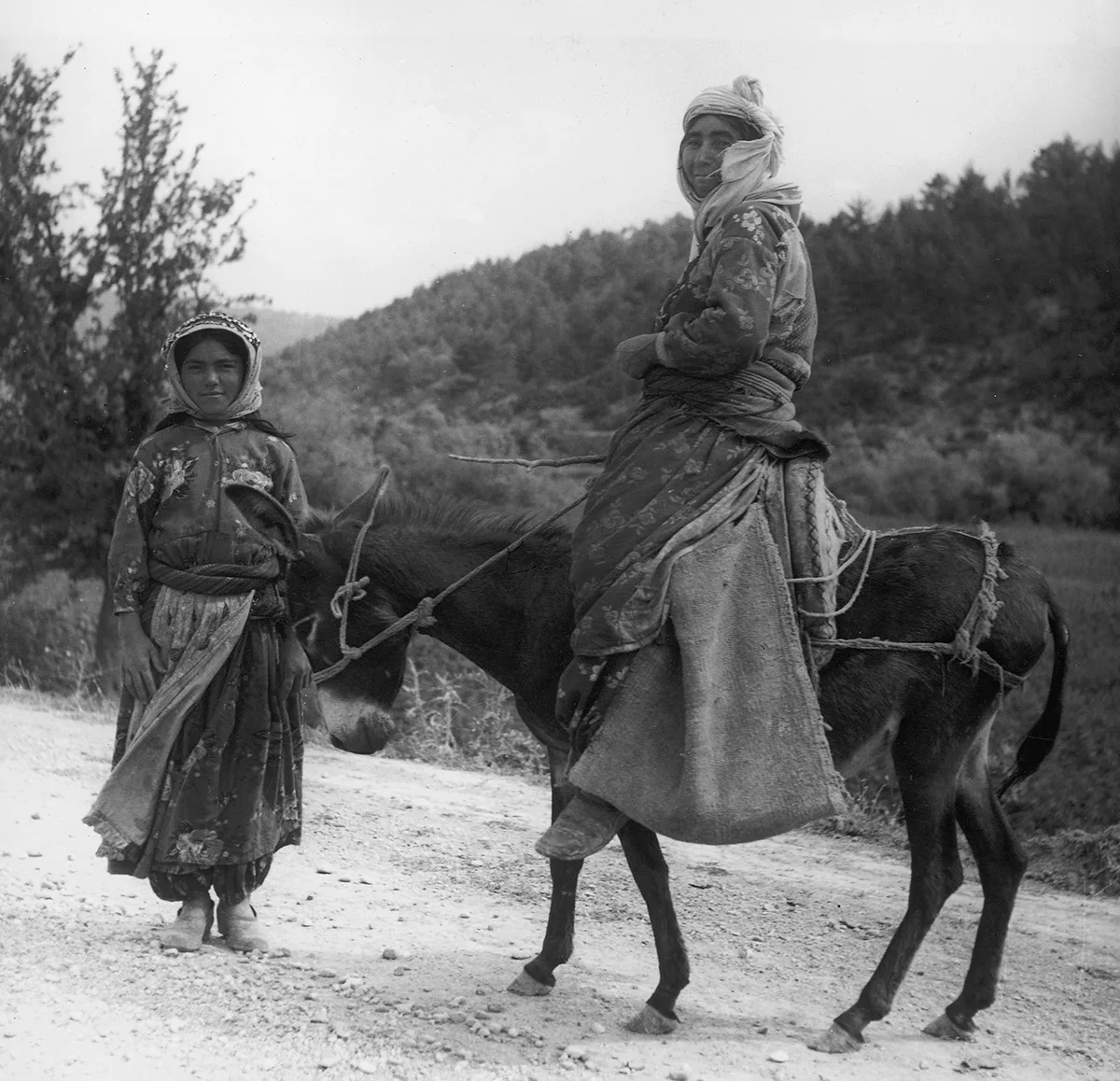

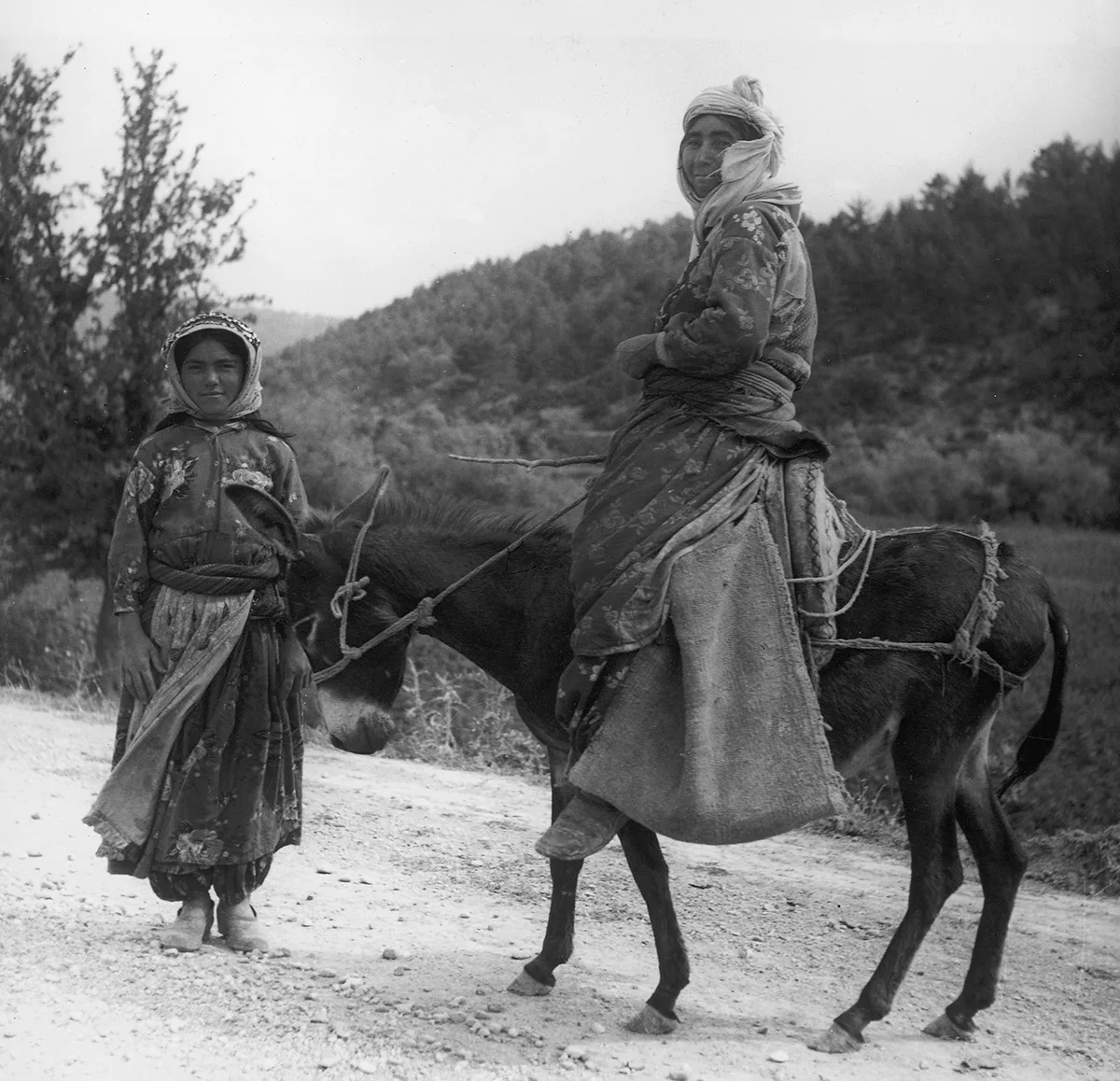

In 1960, feminist Iris von Roten drove all the way to Turkey on her own. It was a trip that would straddle the boundaries between conservative role models and an exotic sense of freedom.

![Iris von Roten's book Frauen im Laufgitter ["Women in the Playpen"], published in 1958](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/2020/03/frauen-im-laufgitter-scaled.webp)

In 1960, feminist Iris von Roten drove all the way to Turkey on her own. It was a trip that would straddle the boundaries between conservative role models and an exotic sense of freedom.

![Iris von Roten's book Frauen im Laufgitter ["Women in the Playpen"], published in 1958](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/2020/03/frauen-im-laufgitter-scaled.webp)