The Jetzer Affair

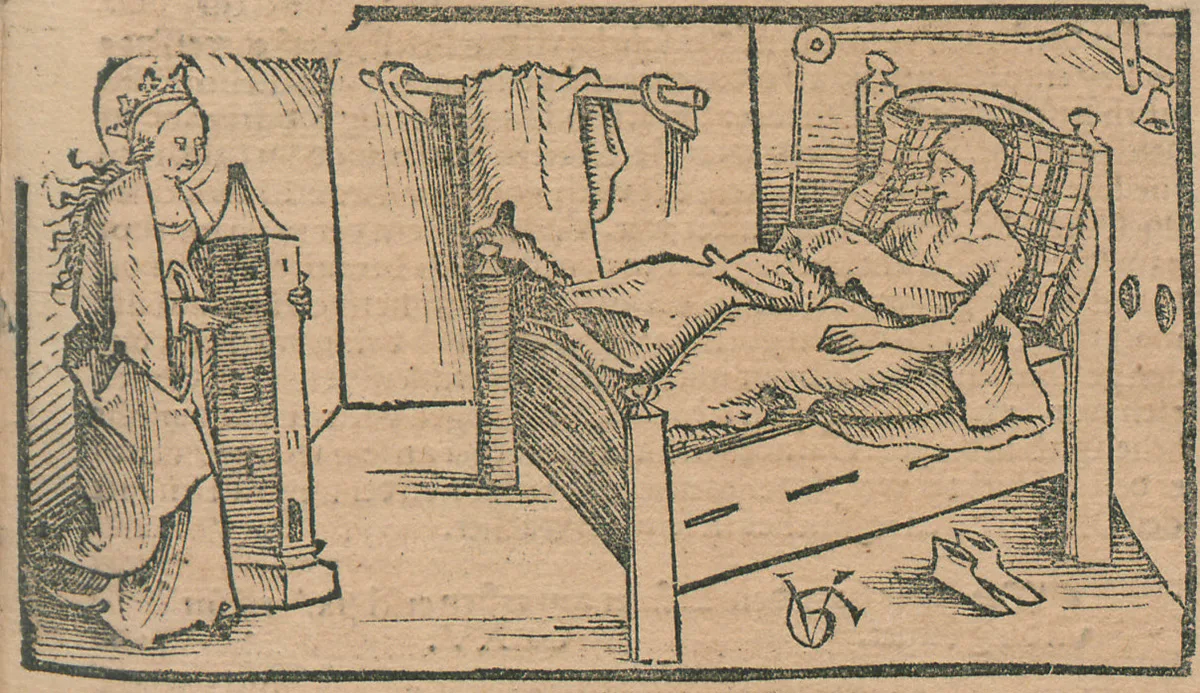

A story of deception, fraud and torture that ends at the stake. The Jetzer Affair in Bern was an out-and-out scandal worthy of a modern-day thriller. Its protagonist was a young tailor's assistant who experienced mysterious spiritual apparitions in 1507. As it turned out, they were much more earthly visions.

The Jetzer Trials

The question of guilt

In her book on the subject, Warum Maria blutige Tränen weinte. Der Jetzerhandel und die Jetzerprozesse in Bern (1507-1509), Kathrin Utz Tremp offers a detailed examination of the Jetzer Affair and the Jetzer Trials. It was published in 2022 as part of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica series from the Harrassowitz Verlag.