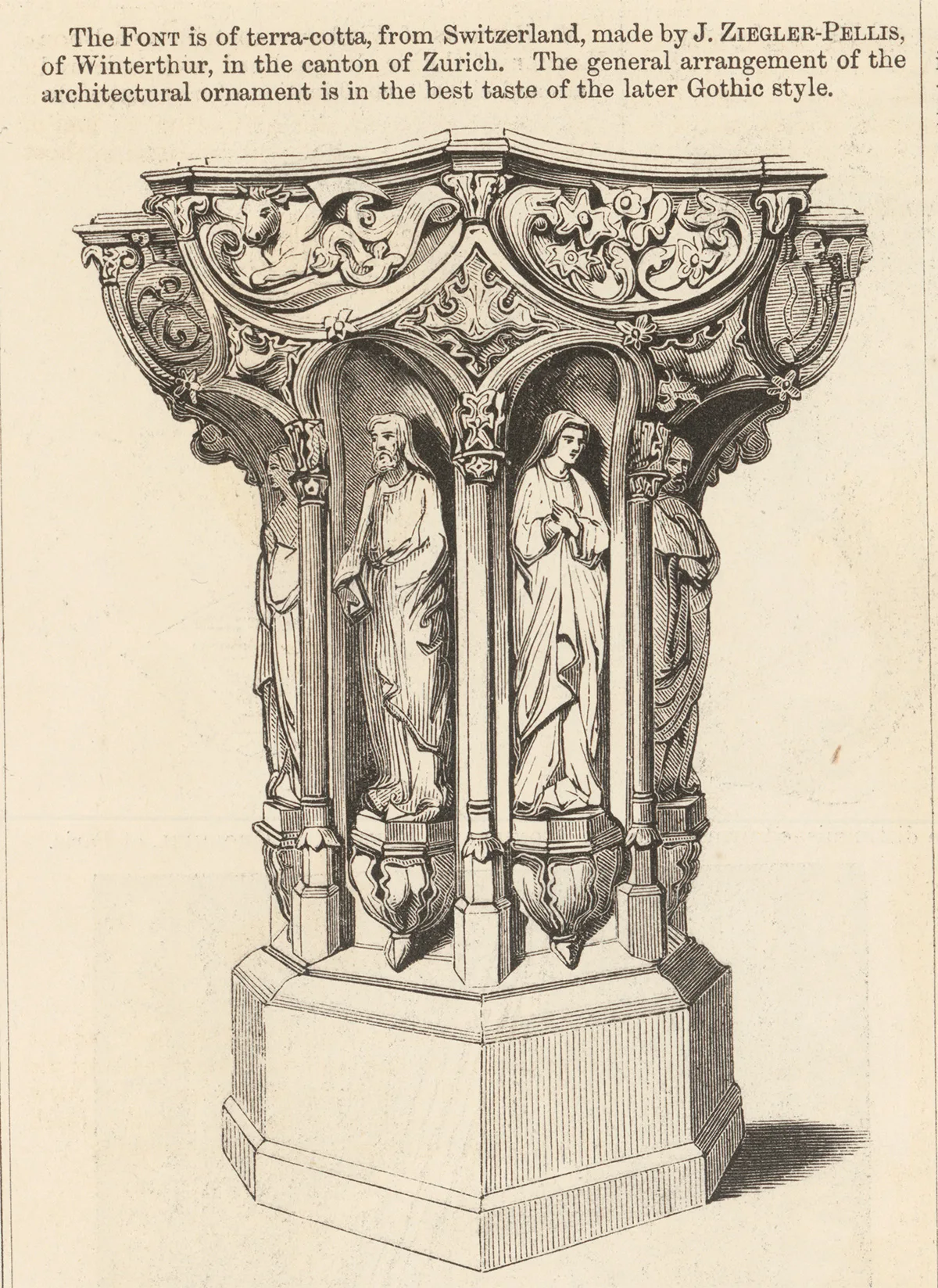

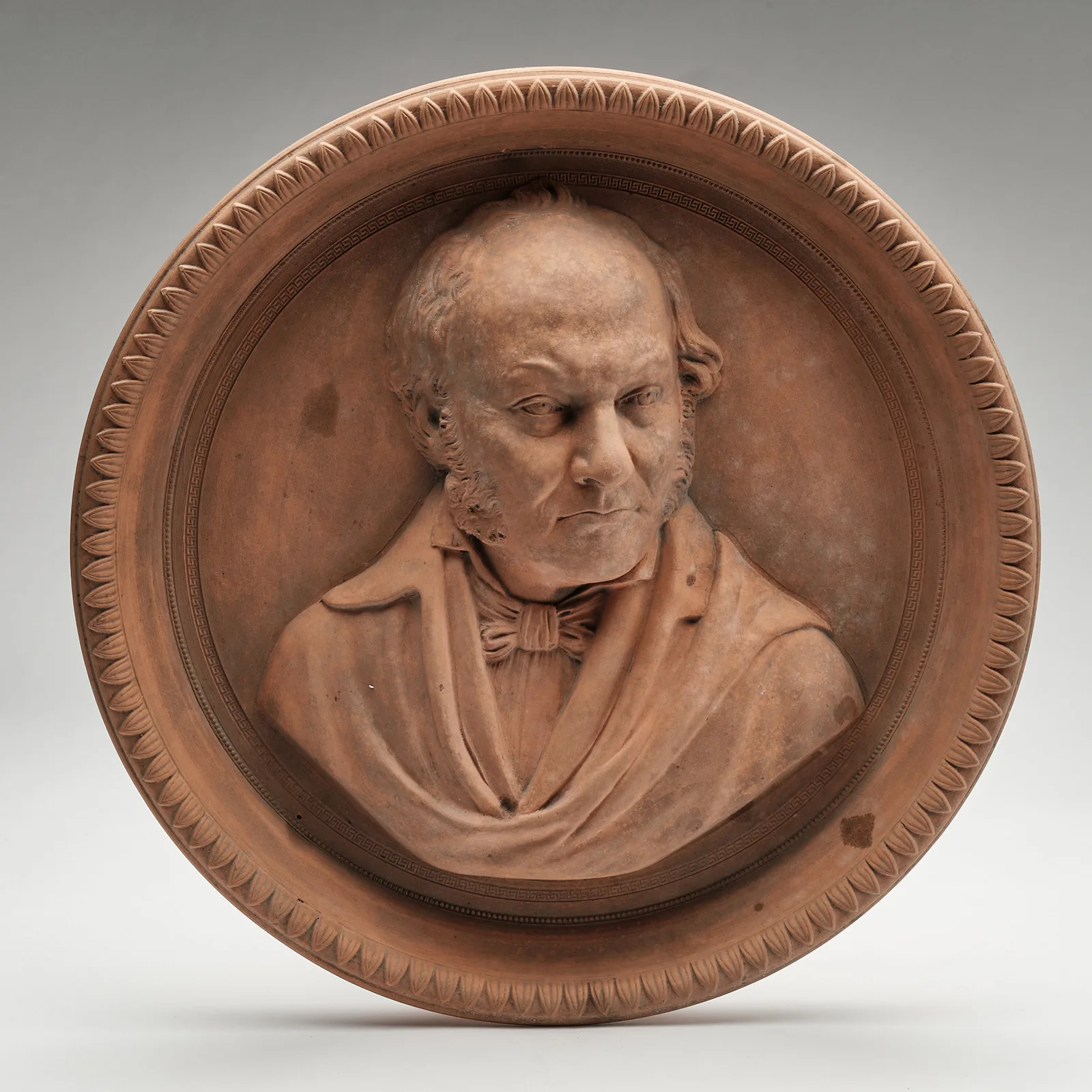

Jakob Ziegler: industrial pioneer and self-made man

Winterthur native Jakob Ziegler (1775–1863) is one of Switzerland’s most remarkable industrial pioneers, and is of great importance to the industrial heritage of the Schaffhausen region.

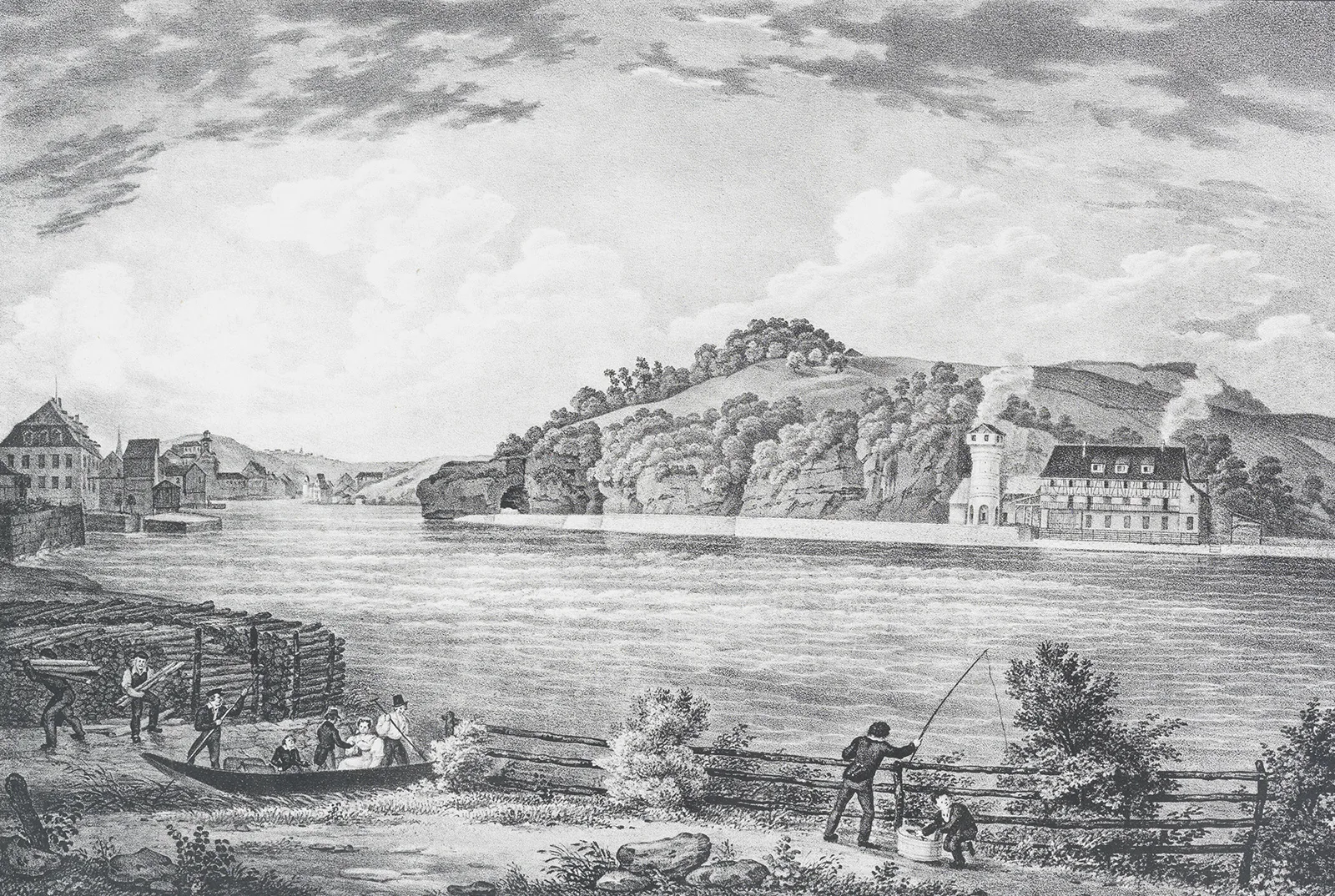

The move to Schaffhausen

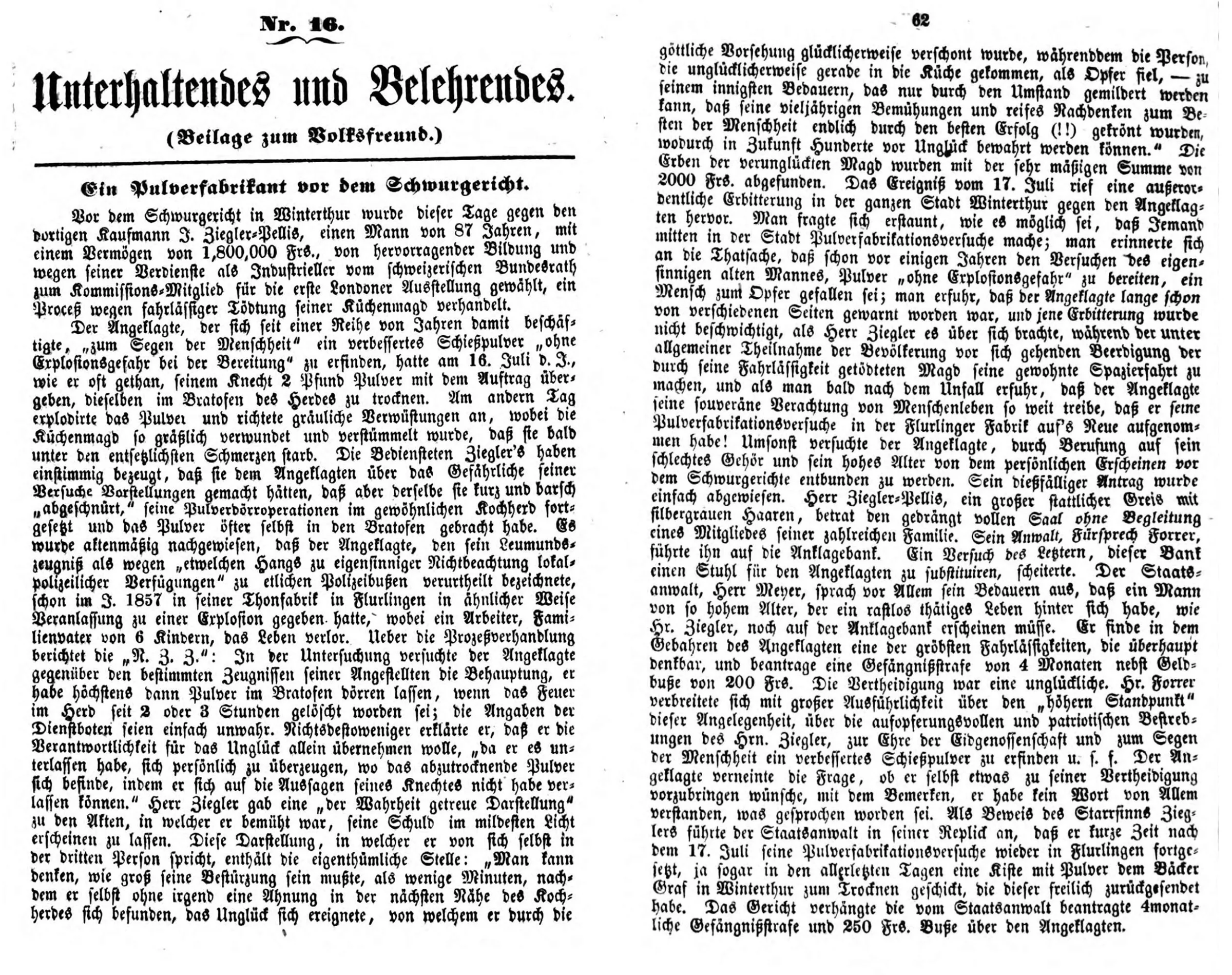

Sensational court case

De mortuis nil nisi bene