National identities

The Czechs have Jan Hus, the French have Joan of Arc, the Greeks have Alexander the Great: each country tells stories about its own past. This is a very humanistic way to create a national identity.

In this day and age, the notion of national identity can be perplexing. And yet we all realise, after spending a few years in another country, that the people there are somehow different. But what really makes this difference? What is it exactly that shapes a nation’s self-image and holds a community together? The language, the boundaries, a shared religion, common enemies, economic interest, the customs or the vegetation – all kinds of things come to mind. But a nation’s self-image is based on something else altogether: a shared narrative, a collective perception of togetherness, that is told and retold, rewritten and reinterpreted, over and over again.

Helvetian

It is said that in Switzerland, even Catholics and Jews are Protestant. Traits like frugality, hard work and punctuality are often associated with Protestantism. After many local ‘reformations’ it was John Calvin who finally sought, in his work Institutes of the Christian Religion (Institutio Christianae Religionis), to bring together the many divergent strands of reformational doctrine. It is also said about Switzerland that its Alps are an undeniable idyll. That is beyond dispute, but the Alps extend from Slovenia to France. The novel Emile or On education (Emile ou De l’éducation) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, son of a Geneva clockmaker, is a treatise on how children may best be educated to be mature, responsible citizens, if this is done in a natural setting, far away from civilisation and urban decadence. Or we could mention the proverbial Swiss ability to compromise. The cantonal majority (Ständemehr), the right of referendum, the long-standing federal structure and the consultation process are witness to the idiosyncratic nature of our country. Even the Swiss chronicles told of the desire for unity, with the metaphor of the three mismatched Swiss confederates in the Rütli meadow. And an example of neutrality: the basic idea of international humanitarian law is found in Henri Dunant’s A Memory of Solferino (Un souvenir de Solférino), which proposes that wounded soldiers be cared for in accordance with the principle of neutrality.

Collective self-image

So what makes the Swiss different from the Norwegians, the Greeks, the French or the Czechs? It is the ideas and constructs derived from their stories. The Norwegian spirit of discovery and daring is based on the resolutely maintained Old Germanic legal institution the Jarltum: a warrior decides for himself which leader he wants to follow. The Atlantic conquests, discoveries including America, and even political liberalism are associated with this handed-down idea of individual liberty. The Greeks, of course, are united by their antiquity, such as the legends of Alexander the Great and his early death, which for nearly two millennia is supposed to have stood in the way of the formation of a united Greek state. Important French myths are the legends about the young Gaul Vercingetorix victoriously leading his troops against Caesar, the stories surrounding Joan of Arc, and the events of the French Revolution. Powerful images of the ‘Grandeur de la France’ are the storming of the Bastille or, in a less martial vein, the Tennis Court Oath establishing the constitutional state – the first in Europe – giving France a special place in European history. The reformer Jan Hus is the Czech hero associated with the centuries-long oppression of the Czechs. Hus chose not to exchange his own life for his principles and convictions, and as a result was burnt at the stake as a heretic during the Council of Constance. These are all identity-forming narratives. Social myths that motivate, guide and create a sense of belonging. Communities are recognisable by their stories.

Just as the question of whether Jesus Christ was really born on Christmas Eve is usually of secondary importance for Christians, deconstructing their particular narrative is irrelevant for a community. Social myths are simultaneously fact and fiction. What matters is that these stories construct a collective self-image and shape a community. For this reason, the plot is always clearly understandable, paradigmatic and affirmative: Joan of Arc is no longer a sectarian virgin, but an ordinary peasant girl with strong convictions. The Vikings are not bullies, but freedom-loving libertarians. Rousseau isn’t a misanthrope, he’s blazing the way for the French Republic. Henri Dunant is not a bankrupt businessman, but the first Nobel Prize laureate. It’s natural for us to treasure pleasing, positive images when it comes to taking action collectively for a whole community.

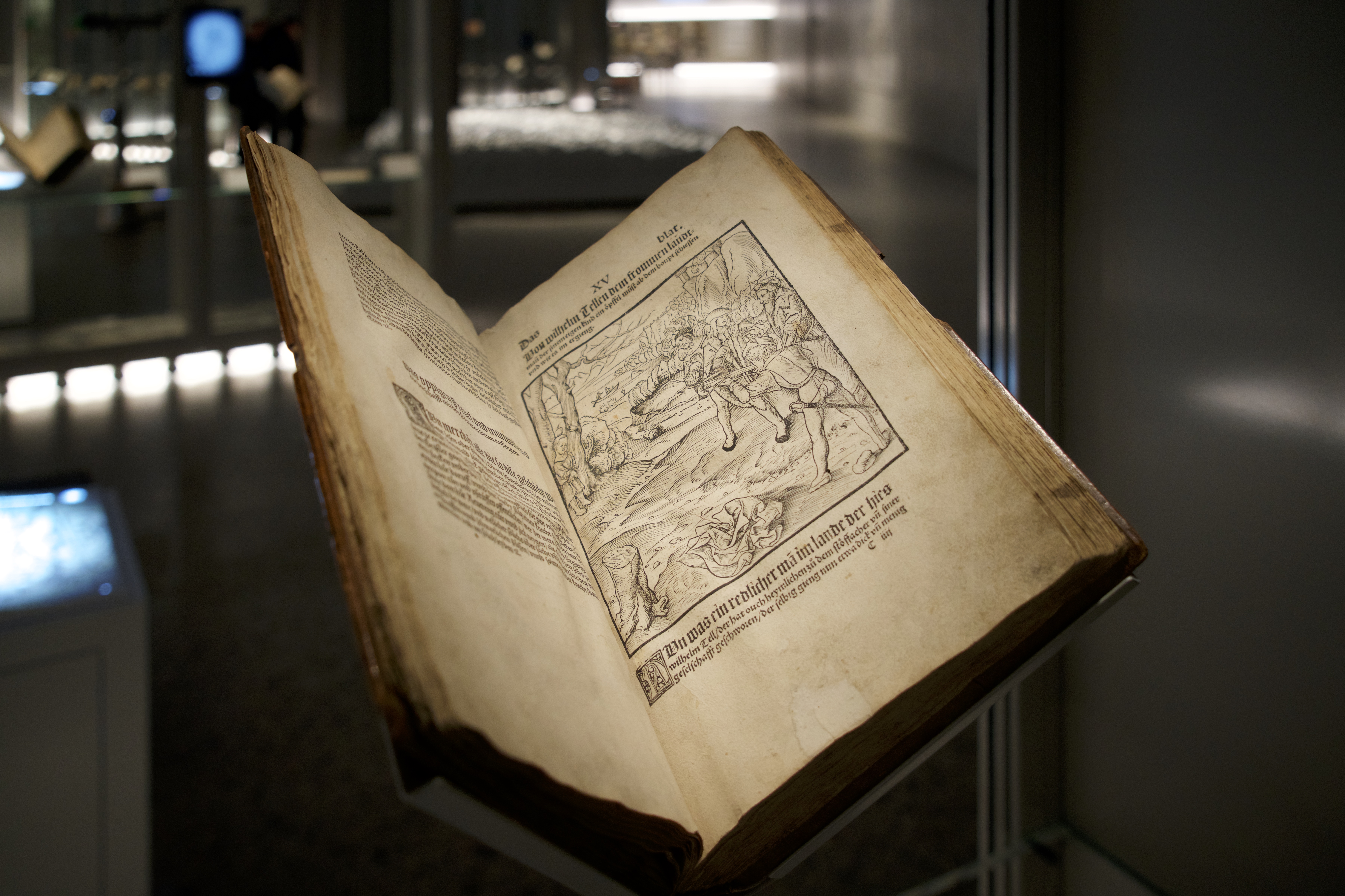

Illustration from Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 1762 work Emile ou De l’éducation, attributed to Jean-Michel Moreau the Younger. Photo: Swiss National Museum

The leader of the Gauls, Vercingetorix, throws down his weapons before Julius Caesar. Historical painting by Lionel Royer, 1899. Photo: Musée Crozatier / Wikimedia

Representation of the Rütlischwur, the historic oath of the Old Swiss Confederacy, on a cabinet from Teufen, Canton of Appenzell Ausserrhoden, around 1782. Photo: Swiss National Museum

Supranational belonging

National identity understood in this form is entirely humanistic. The sense of belonging is not bound to the unchanging and immutable. It is not origins, religion or ethnicity, but narratives that define national identity – narratives that can be internalised regardless of the individual’s background. Even supranational institutions such as the European Union should not be afraid of national identities, values and symbols. In this context, it is worth remembering Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities or Gérard Bouchard’s Mythes sociaux et imaginaires collectifs. Narrative representations would also be helpful for the European Union. The purely pecuniary undertakings of the Europoliticians are no substitute; the repeated exhortations to solidarity even less. The Jacques Delors Institute in Paris recognised this and commissioned historian and sociologist Gérard Bouchard to carry out the study ‘Europe in Search of Europeans’. Bouchard’s diagnosis indicates, apart from making a lot of economic sense, that Europe lacks a cultural dimension of its own. The EU must discover its own elements in order to consolidate its shared identity. Within the community, the social human needs the putty and cement of collective identity.