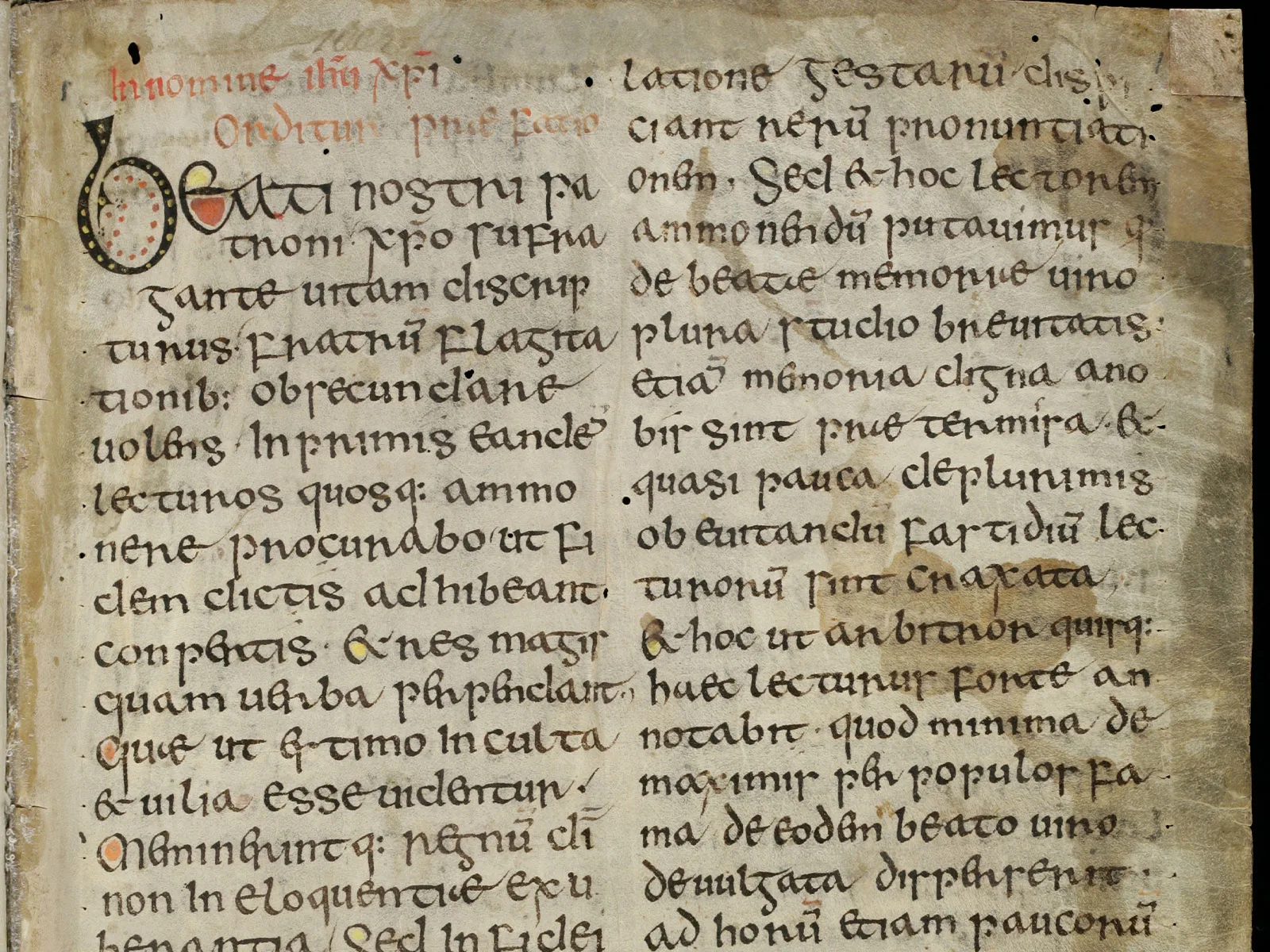

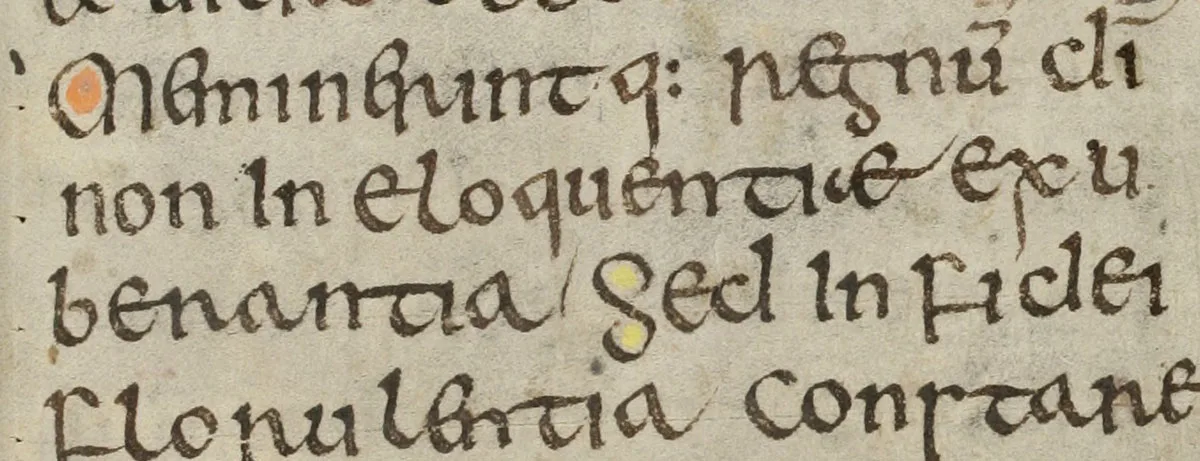

Of Monks and Monsters: The Schaffhausen Vita Sancti Columbae

The Schaffhausen Municipal Library is home to a manuscript of great significance: The Hiberno-Scottish saint’s life of Columba of Iona provides insight into a period of history about which little is known. It also contains the oldest account of a monster in Loch Ness.

Visit e-codices.unifr.ch to explore the digital version of the Schaffhausen Vita Sancti Columbae.