The darkest day in the history of the Swiss Guard

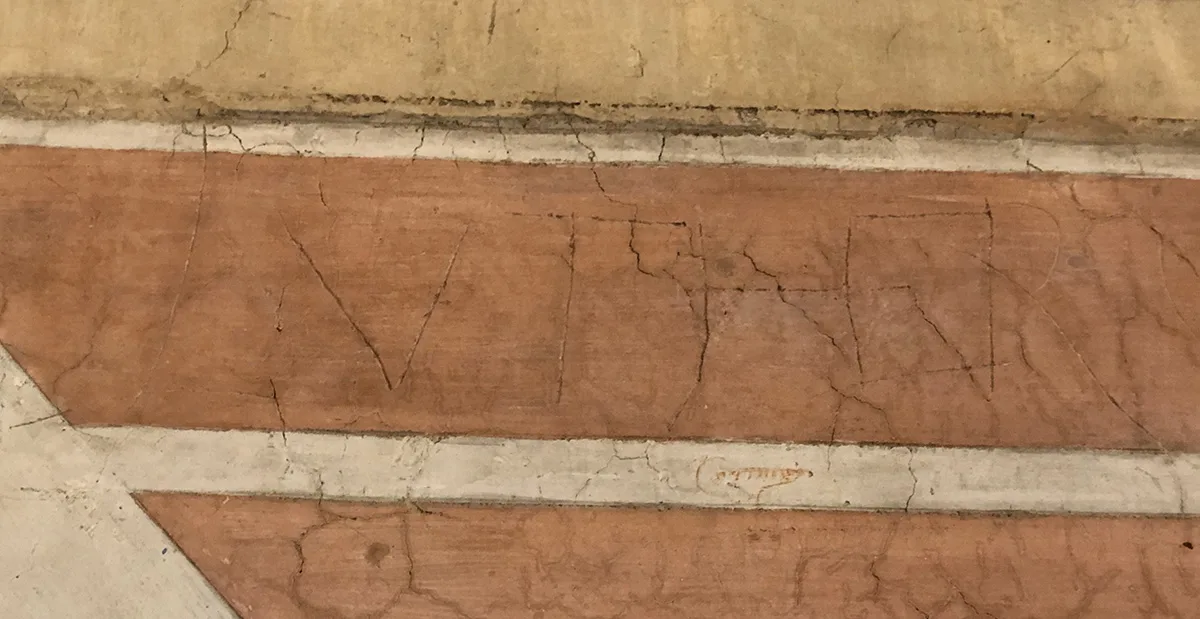

The Sack of Rome, or ‘Sacco di Roma’, by the leaderless troops of Charles V on 6 May 1527 ended in a bloodbath that also cost the lives of 147 Swiss guards. Traces of that dark day are still being discovered.