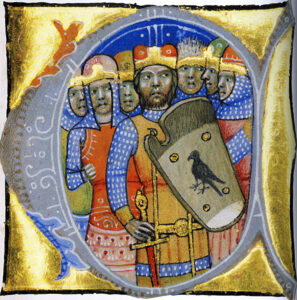

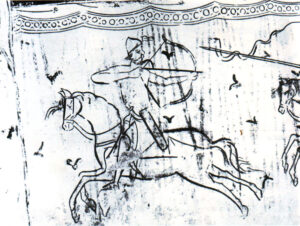

When the Magyars invaded St. Gall

Between 860 and 970, the Magyars were the scourge of Europe. They devastated and pillaged a wide swath of territory from Bremen in the north, to Otranto in the south, and Orléans in the west in a series of over 50 raids. The abbey of St. Gall was raided and sacked in 926. Thereafter, monks in St. Gall wrote and preserved the most detailed and oldest first-hand descriptions of the Magyar invasions of Western Europe.

…ab Ungerorum nos defendas iaculis….De sagittis Ungarorum libera nos, Domine…

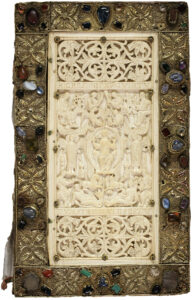

St. Gall & Preparations for the Sack

The Sack & Historical Memory