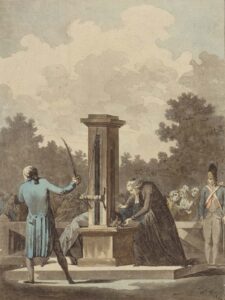

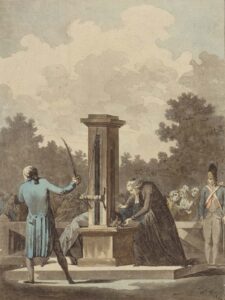

The guillotine maker

Johann Bücheler was a regular carpenter from Kloten. In 1836, he was commissioned by the canton of Zurich to build a guillotine. That proved the end of “normality” as he knew it.

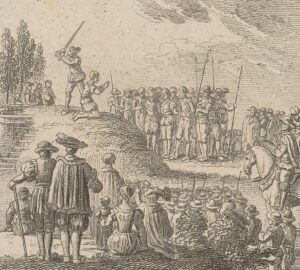

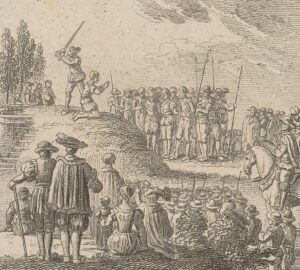

No-one likes an executioner

Johann Bücheler was a regular carpenter from Kloten. In 1836, he was commissioned by the canton of Zurich to build a guillotine. That proved the end of “normality” as he knew it.