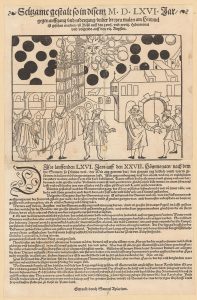

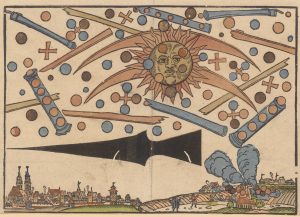

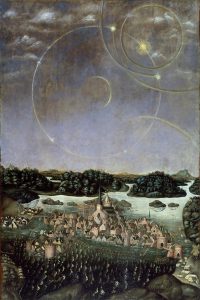

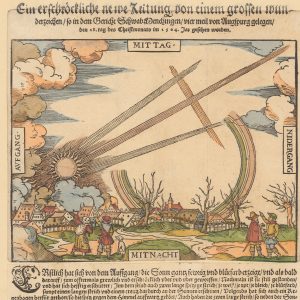

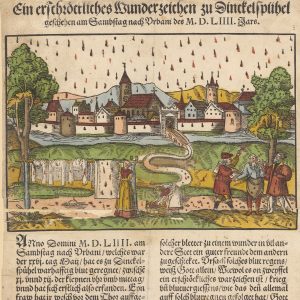

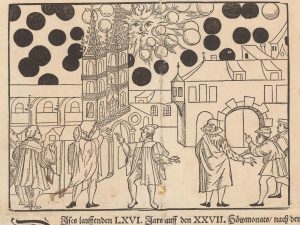

The celestial event over Basel in 1566

A dazzling array of celestial phenomena occurred over the skies of Basel in July and August 1566. The spectacle was so unusual that it precipitated much public discussion and the publication of a leaflet which reflects a Switzerland grappling with deep social unease and tensions.