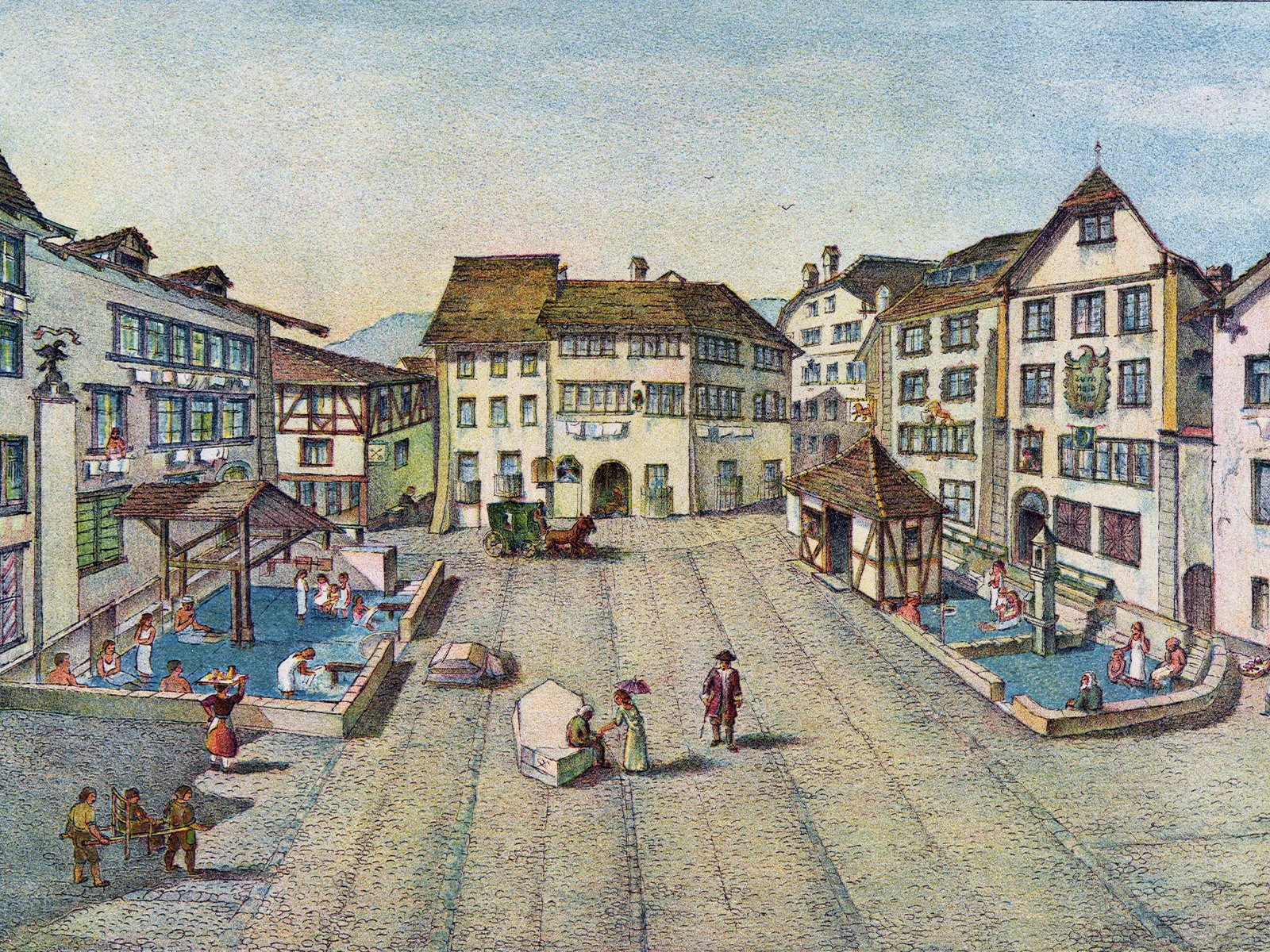

Isis and Verena: two holy women at Baden’s healing springs

At the thermal springs in Baden, the Romans worshipped a goddess with her roots in Egypt. After the Baden region converted to Christianity, a saint from Lower Egypt became the patroness of the spa town on the Limmat.

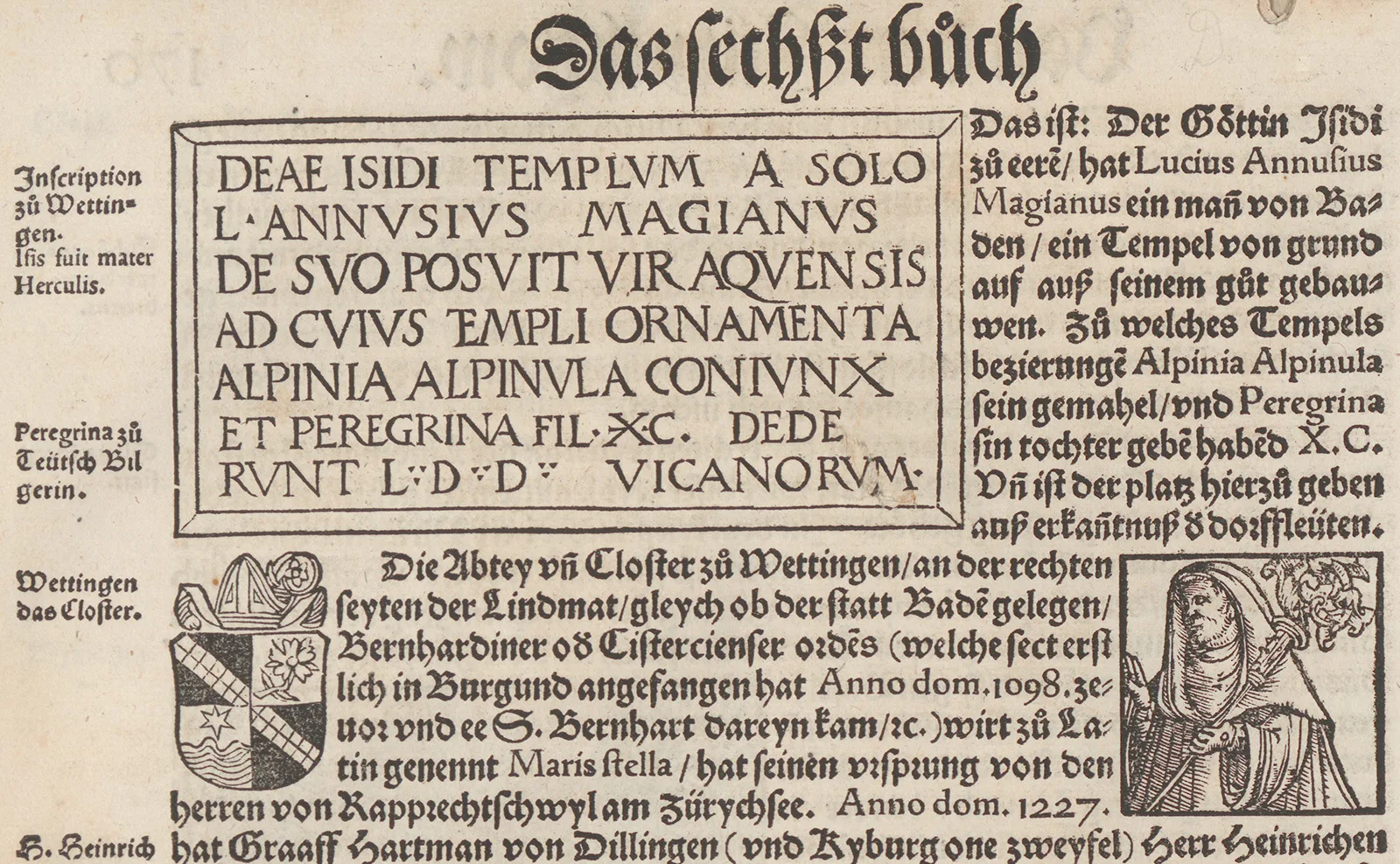

The Roman goddess Isis was worshipped in Baden

Patron saints in the Middle Ages

A chance similarity?