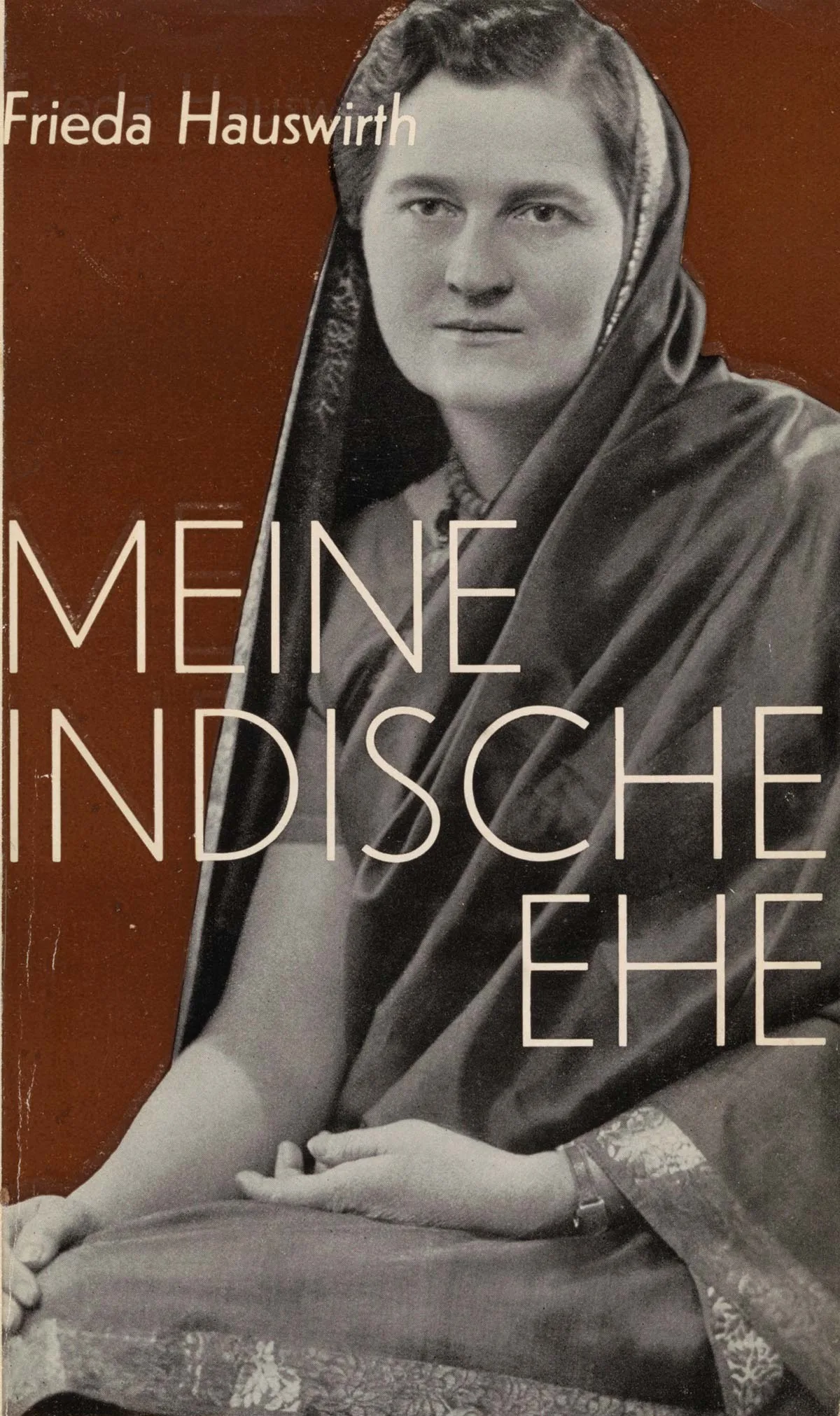

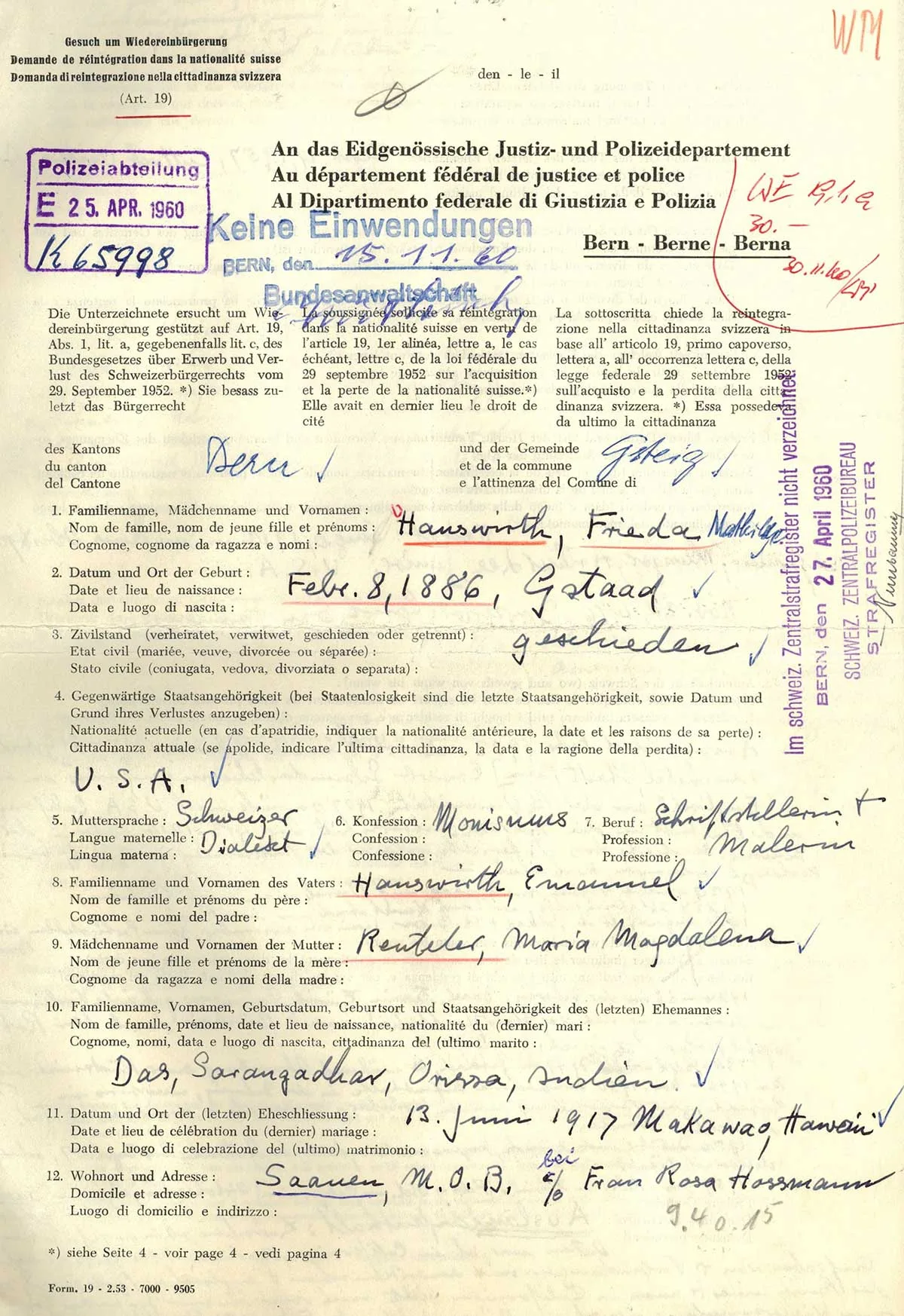

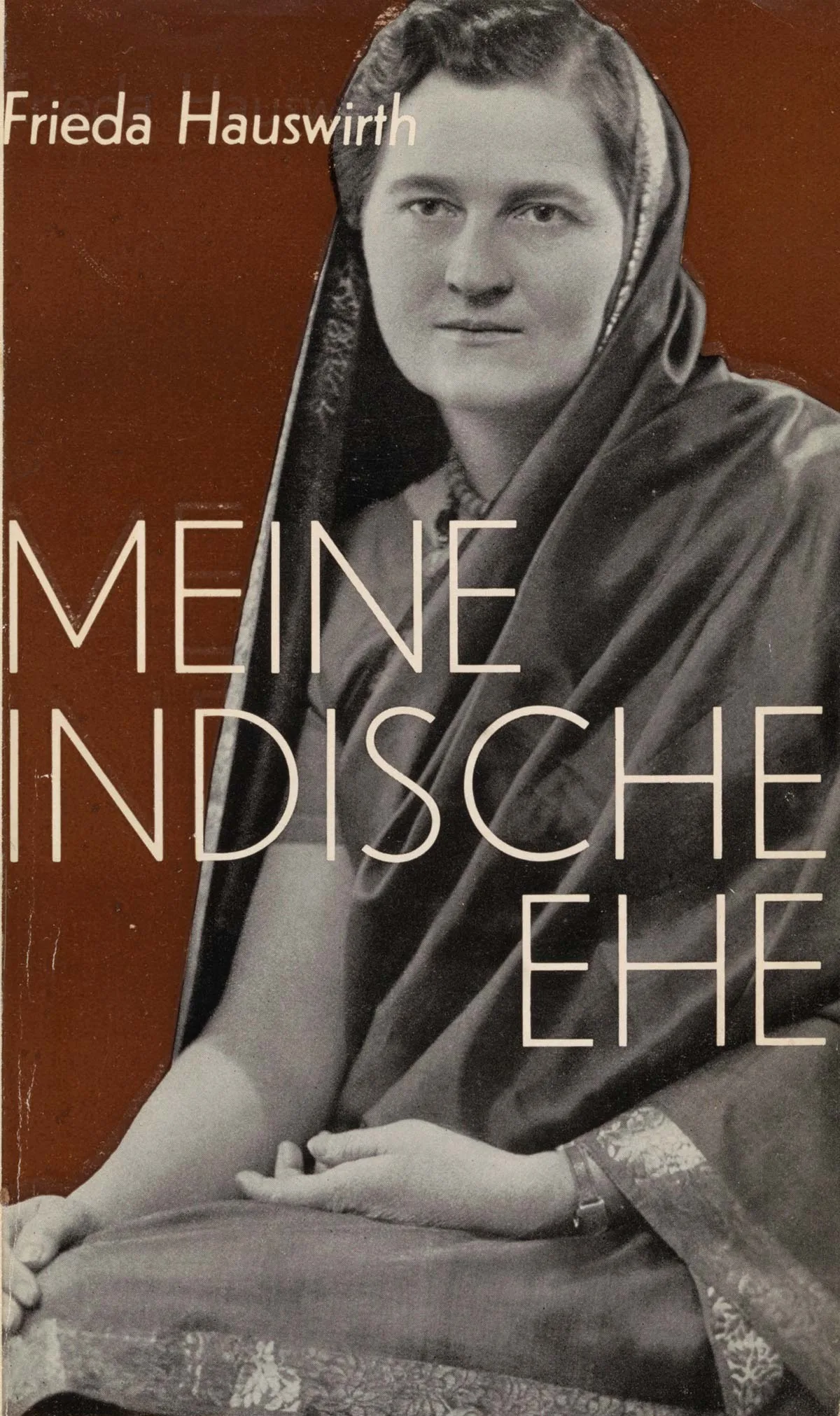

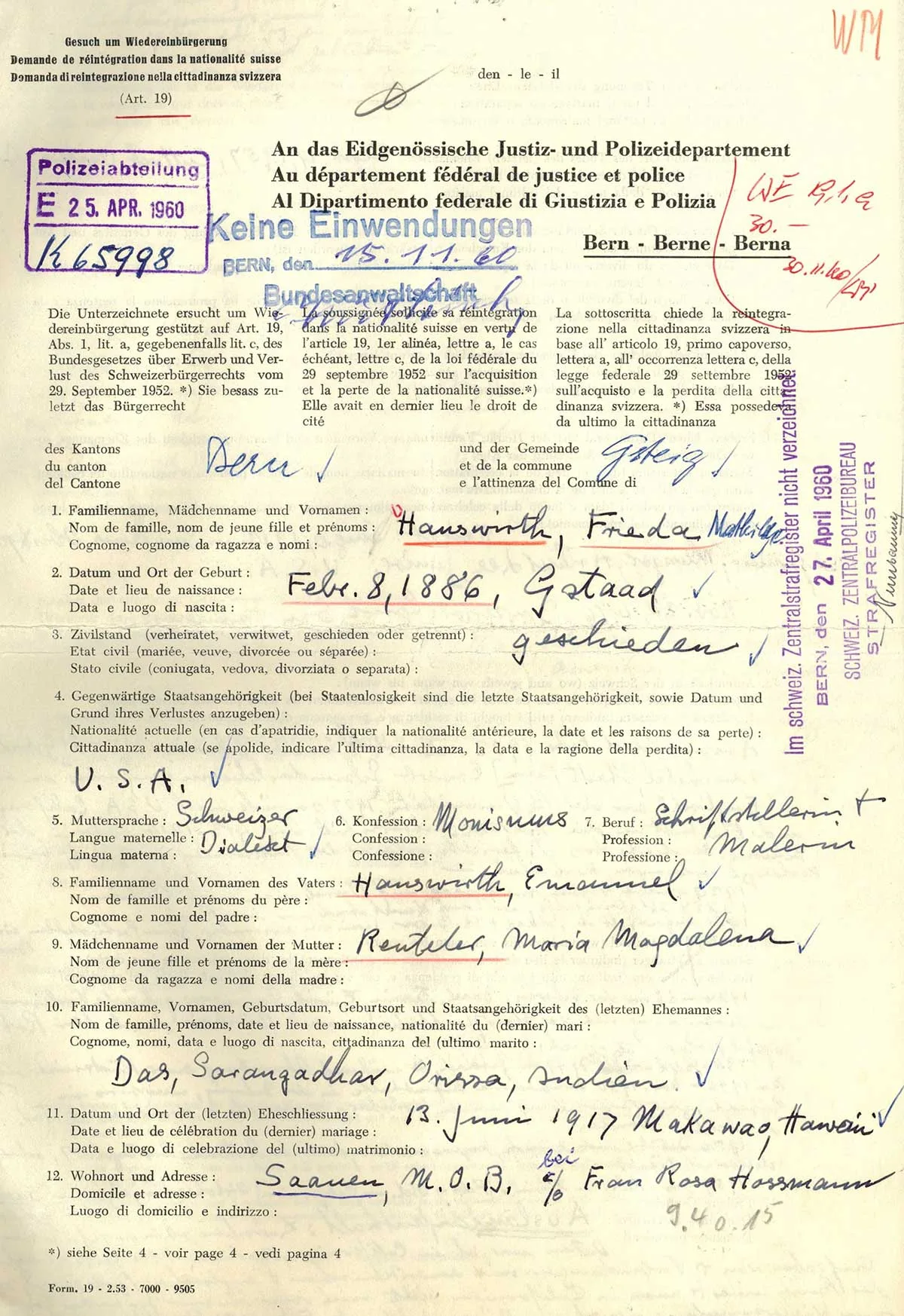

A citizen of the world, born in Gstaad

Frieda Hauswirth was a Swiss national, US citizen and British subject: one woman's odyssey across continents and corridors of power.

Frieda Hauswirth was a Swiss national, US citizen and British subject: one woman's odyssey across continents and corridors of power.