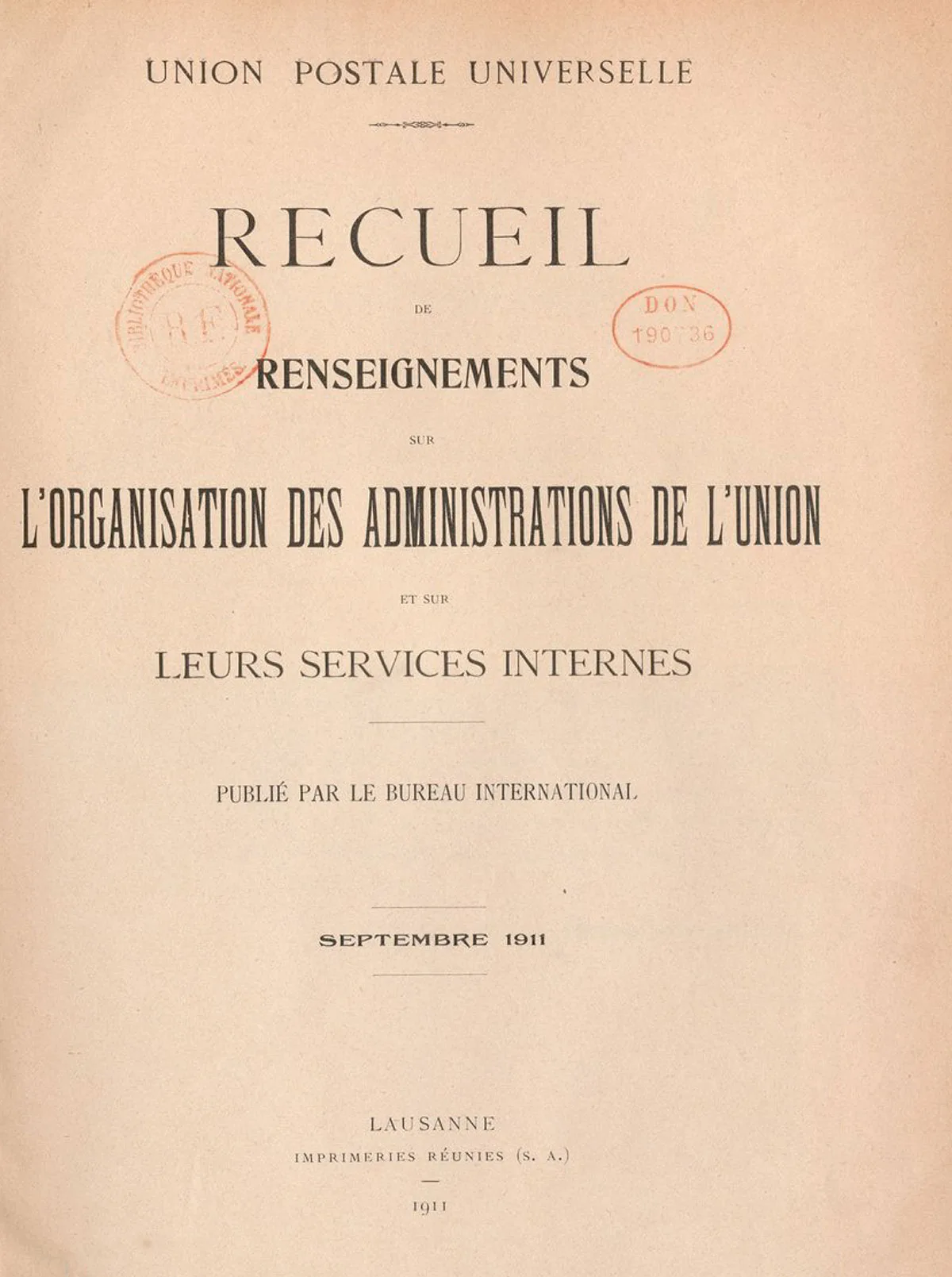

The story of the Universal Postal Union

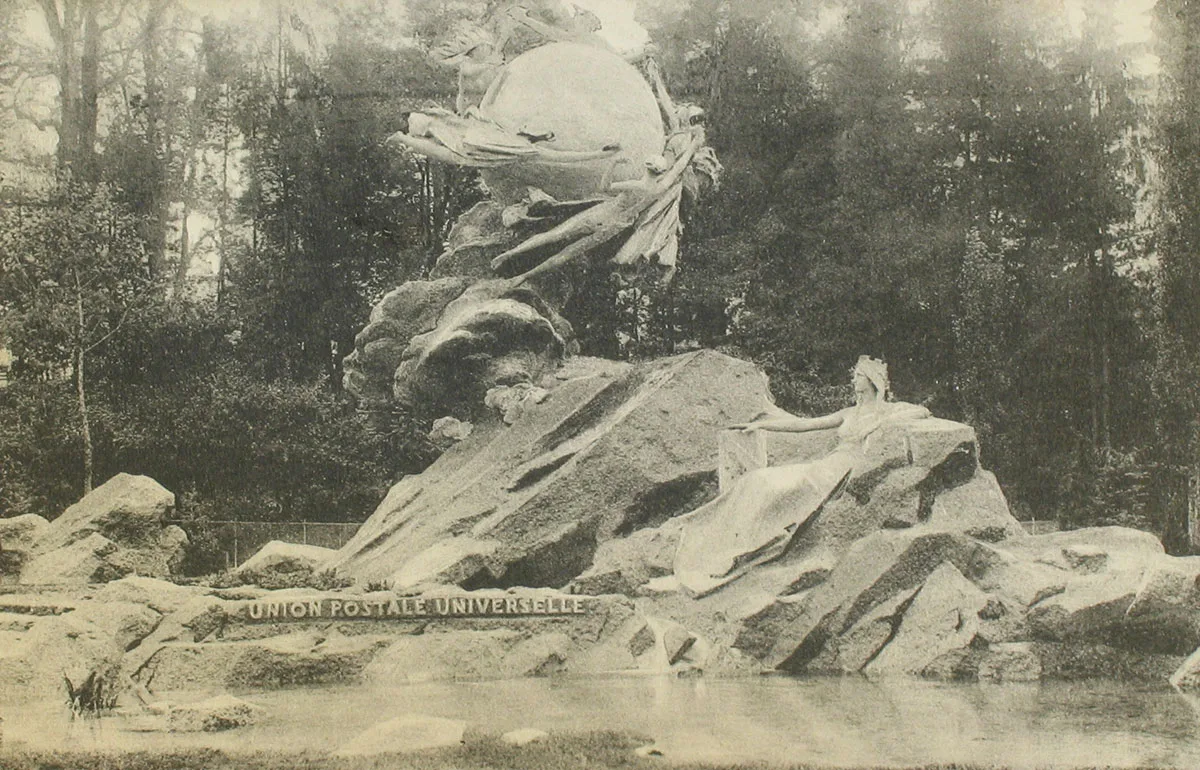

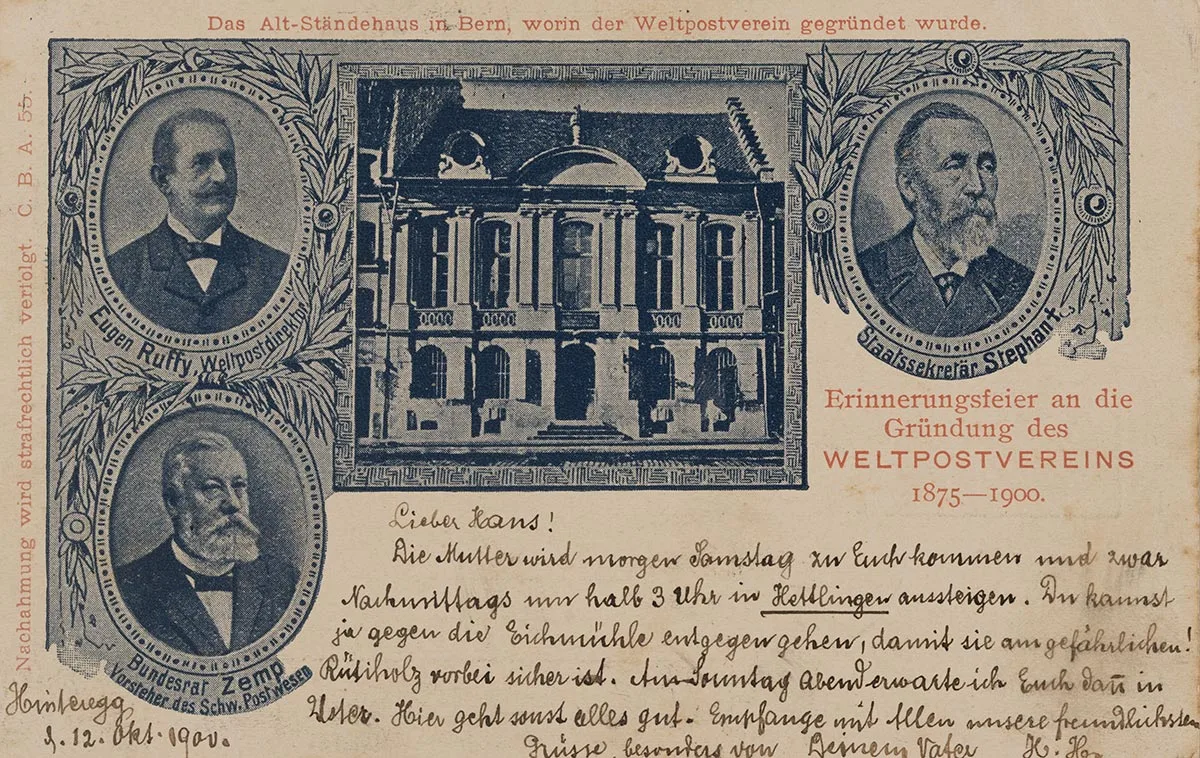

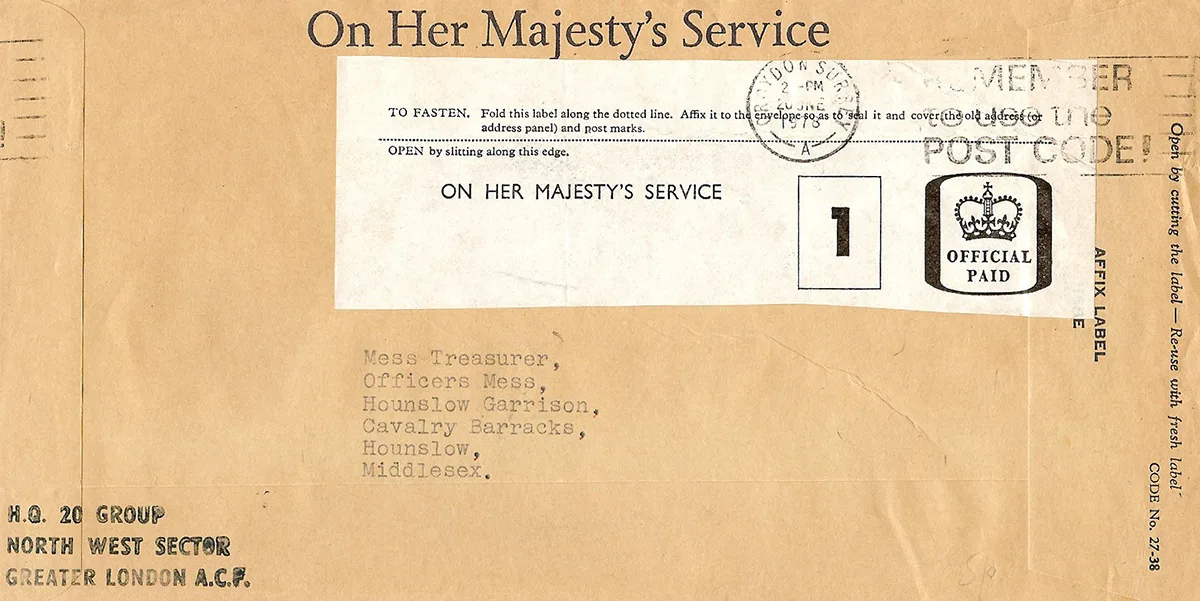

On 9 October 1874, the Universal Postal Union was established in Bern, laying the foundation for modern communication. To this day, it allows the global exchange of letters and parcels and is a cornerstone of global postal traffic.

An international organisation for millions of people

Fragile freight for bee keepers

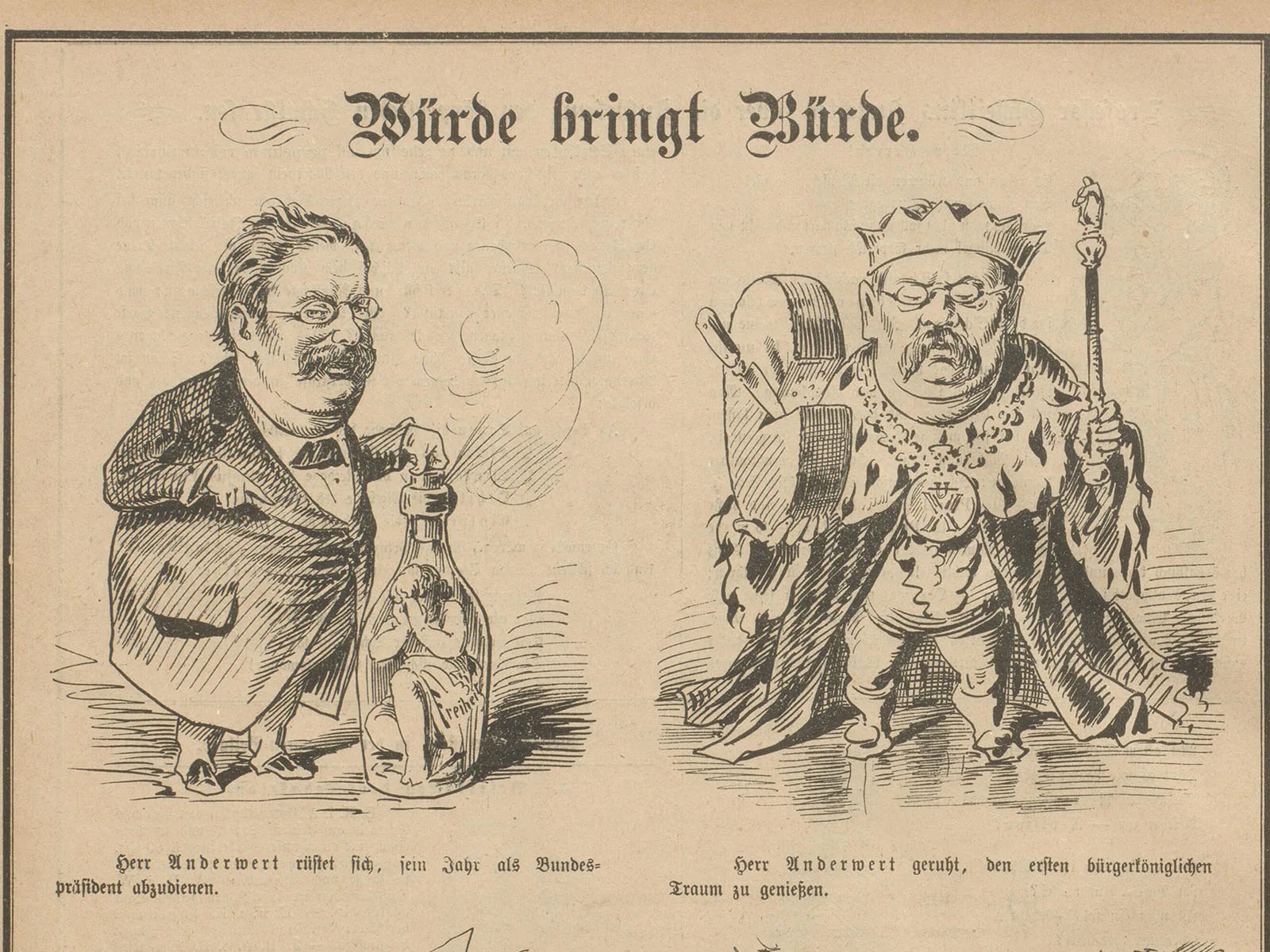

Postal accounts for women and discounts for ruling princes

Collaboration

This text was born of a collaboration between the Swiss National Museum and the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland research centre (Dodis). Madeleine Herren is Chair of the Dodis Commission and co-editor of the source edition Die Schweiz und die Konstruktion des Multilateralismus (‘Switzerland and the construction of multilateralism’) volume 1, published in 2023.