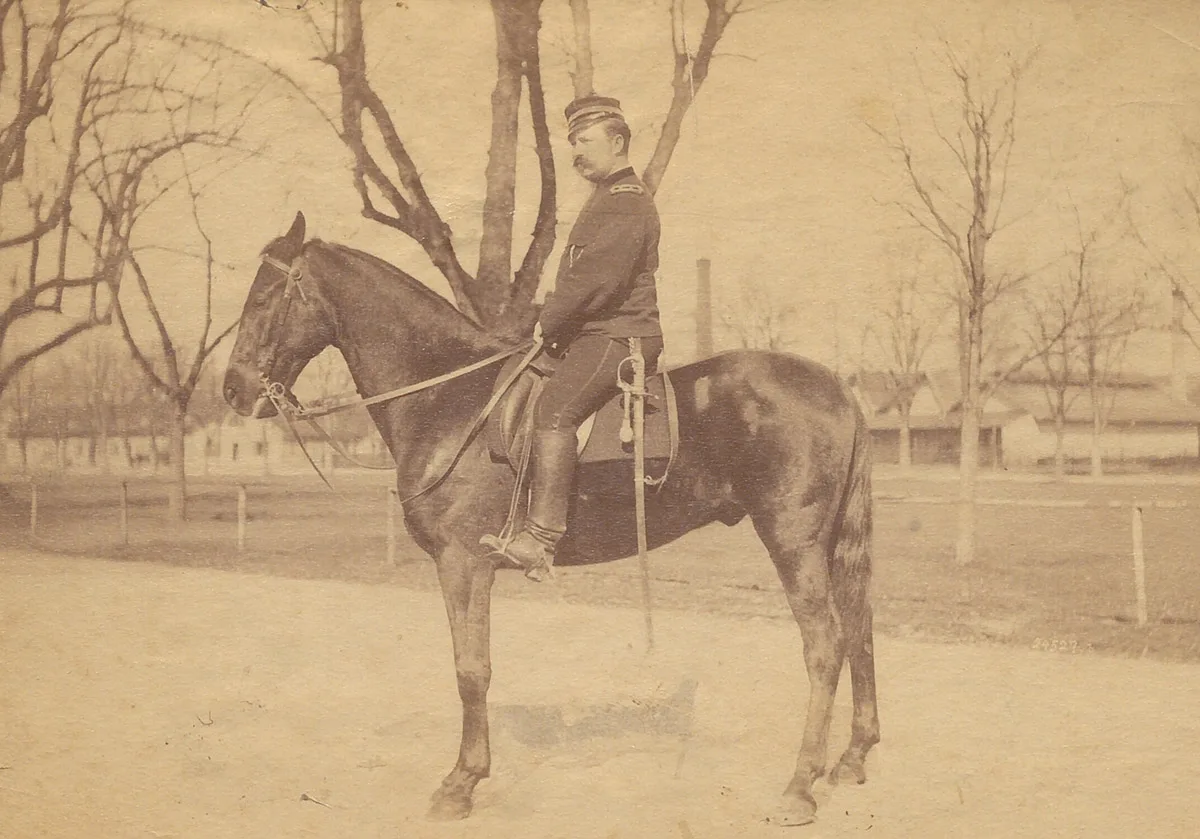

General Wille – Switzerland’s popular and embattled military leader

In 1914, Switzerland mobilised and had to appoint a general. The Federal Council and Federal Assembly could not agree on whom to choose. Following a private chat with the other candidate, Ulrich Wille got the job.

From dismissal to promotion

General Council 1914 to 1918

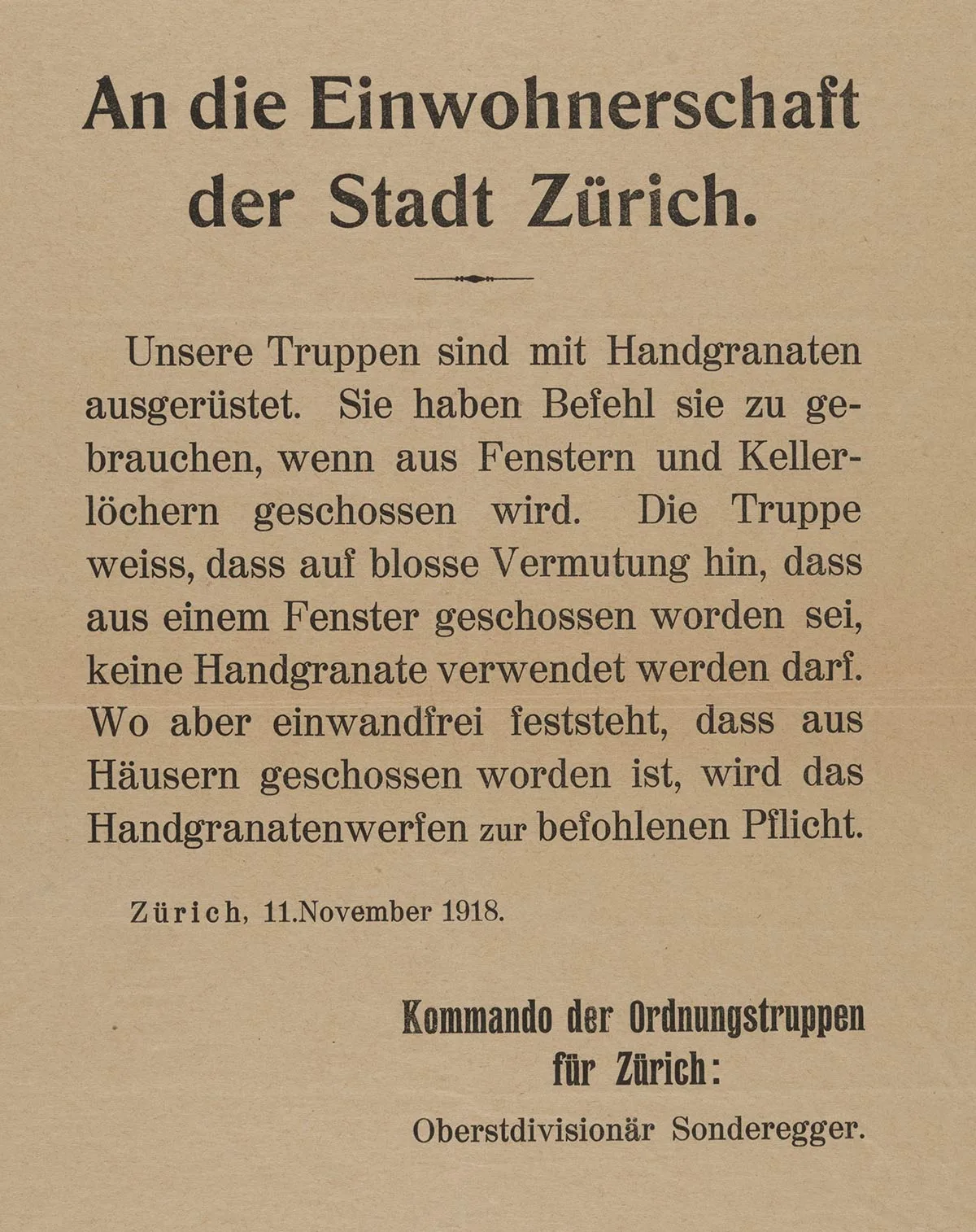

1918 general strike: how to respond in the event of a socialist coup?