Visiting the Rigi used to make people ill, why?

120 years ago, many people complained of severe diarrhoea and vomiting following a visit to the Rigi. For a long time, people blamed the ‘Rigikrankheit’ (as the condition was known) on the mountain air, until a high profile defamation trial uncovered a major environmental scandal.

In 1909, however, the ‘Rigikrankheit’ became too much, or ‘virulent’ as a subsequent investigative report stated. Entire classes who had visited the Rigi on a school trip fell ill, severely so in some cases. The Zurich city doctor documented 287 cases, which he had personally encountered. In one class, all the children were afflicted with severe vomiting and diarrhoea, and 21 of 26 pupils in another class fell ill, plus all the adults.

School trips banned

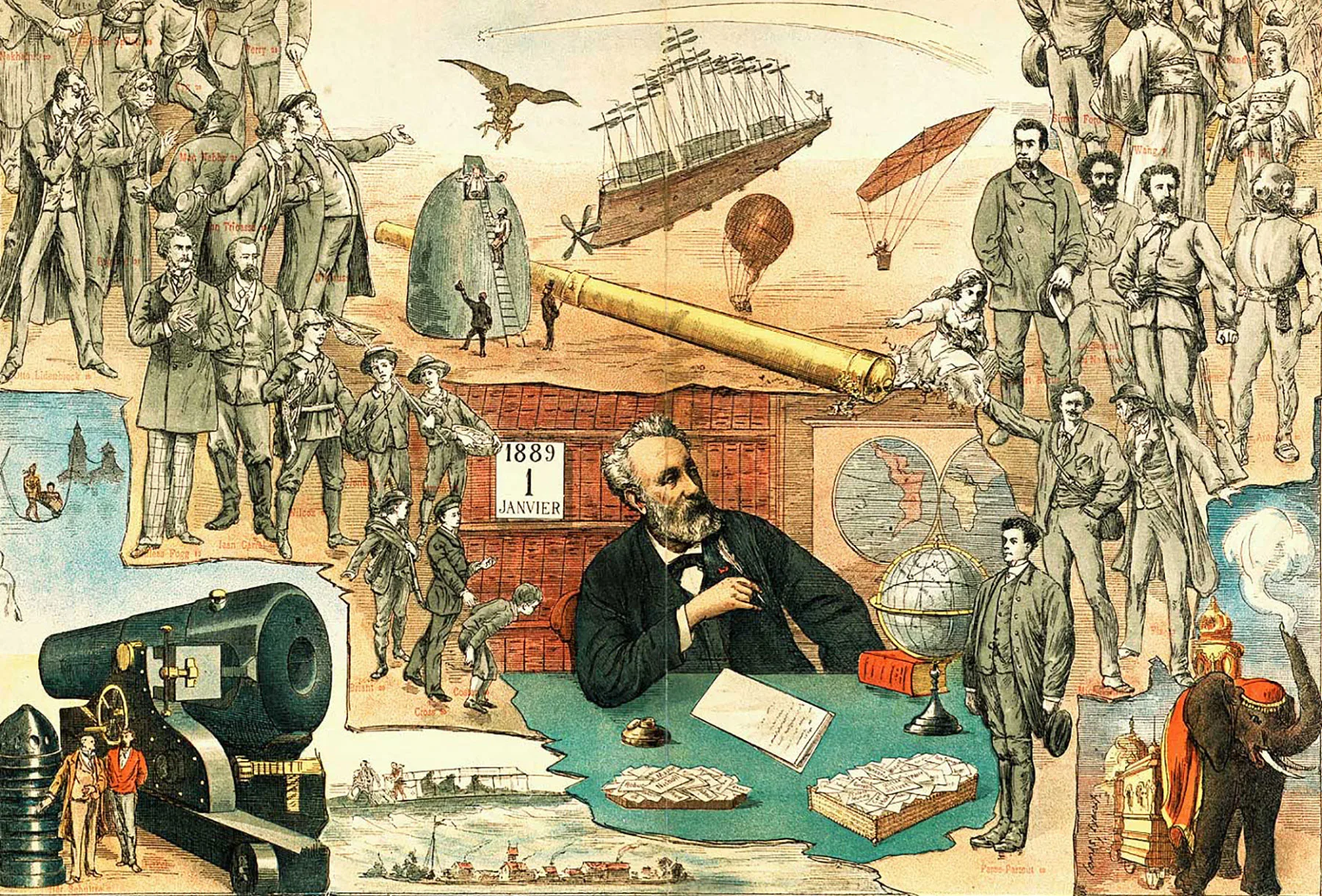

The Rigi was Europe’s ‘in’ mountain during the 19th century. By 1840, it had about 40,000 visitors every summer, rising to 70,000-80,000 following the construction of Europe’s first mountain railway in 1871. There were many grand hotels at Kulm, Staffel, Klösterli, Rigi-First, Scheidegg and Kaltbad where people could stay. The mountain had a total of about 2,000 hotel beds.

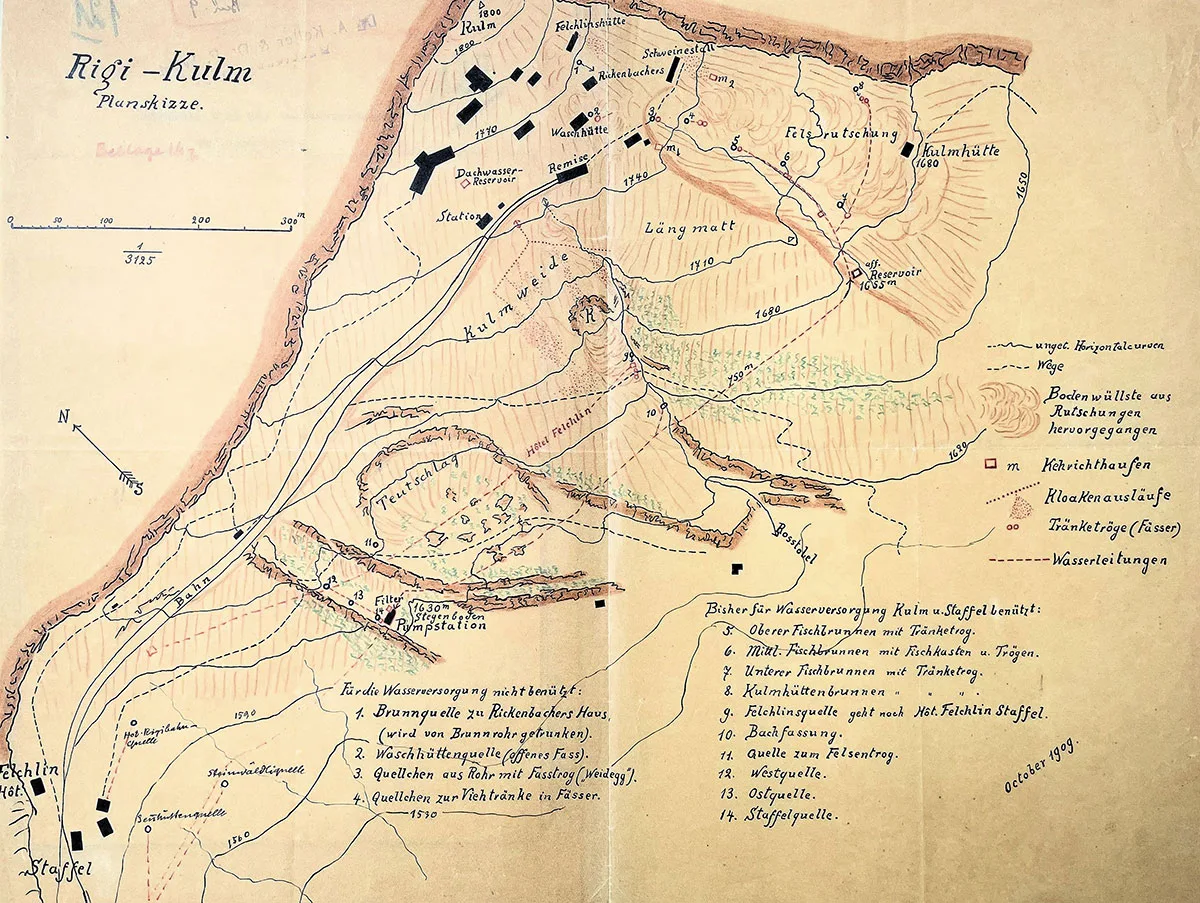

The large Kulm and Staffel hotels were the worst. They drew drinking water from different sources as well as from the rainwater on the roof. All the sources merged into a big reservoir – including the wastewater from the hotels located higher up, which was expelled into a field from where it flowed down almost unfiltered into a well further down the mountain. It was then pumped back up from the reservoir as drinking water to the hotels higher up.

In parallel with the investigations by Carl Real, Professor Oskar Wyss, Head of Zurich Hygiene Institute also got to work. The manager of the Kulm hotel had asked the professor, who was his friend, for an assessment. Wyss enlisted the services of Albert Heim, a prominent professor of geology, who immediately concurred and described the water supply as “highly dangerous, unsanitary.”

Typhoid in Klösterli

In 1909, the environmental scandal finally became public knowledge. The issues with the drinking water supply had already been covered by various newspapers. In 1910, Zurich City Council demanded that school trips only be authorised once the Zurich city or school doctor had investigated the state of the drinking water supply. Progress on the Rigi was slow. Some particularly poor drinking water sources were discarded and the wastewater from Kulm hotel was diverted eastwards over the cliff wall. In any case, even as late as 1912 most of the spring water was captured from old oil barrels buried in the ground.

“Don’t touch a drop”

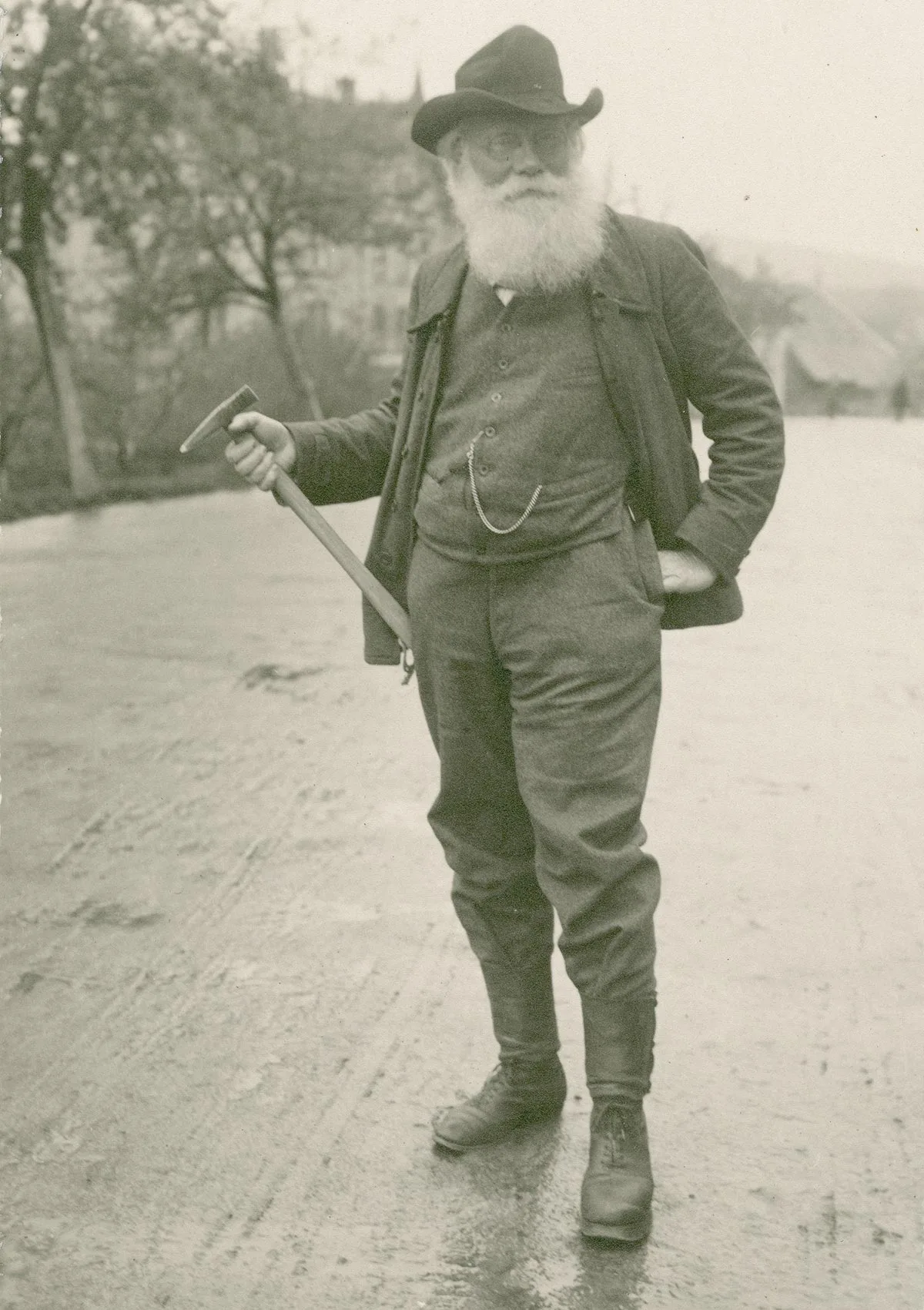

Albert Heim mentioned this in his article – and was promptly sued by Joseph Fassbind for reputational damage. Heim’s article was a bombshell and caused maximum damage according to the libel action. Bookings had fallen massively, claimed Fassbind. Heim contested the allegation that his article had been damaging. The fall in bookings in 1914 had instead been triggered by the outbreak of the First World War, he claimed.

On 3 October 1917, Zurich District Court rejected Fassbind’s claim. It was proven that the water he used came from a highly questionable source. Fassbind appealed to the Cantonal Supreme Court and subsequently came to an agreement with Albert Heim. The case was dropped, and Heim provided an explanation, whereby the water supply in Klösterli had been sanitised “as far as humanly possible”.

The First World War brought all the Rigi hotels to the brink of ruin. The many tourists from abroad disappeared almost overnight. Most businesses did not survive, and the buildings were knocked down, with some burning to the ground. The last known case of typhoid was in 1932, on the Lucerne side of the Rigi, in Kaltbad. This led to a further improvement in the drinking water supply.