Conserved values

The lowly tin can became a household staple in the emerging consumer society of the 1950s. And the way tinned foods were advertised gives us an insight into social and cultural change.

The tin can, which was further refined in subsequent decades, was well suited to the military. The food it contained was non-perishable and its compactness made it easy to transport. In the 20th century, too, the tin can proved effective for stockpiling, particularly in politically turbulent times. During the Second World War, the federal government called on the Swiss people to stock up on tin cans in case of emergency. In short, the tin can came into its own in times of crisis.

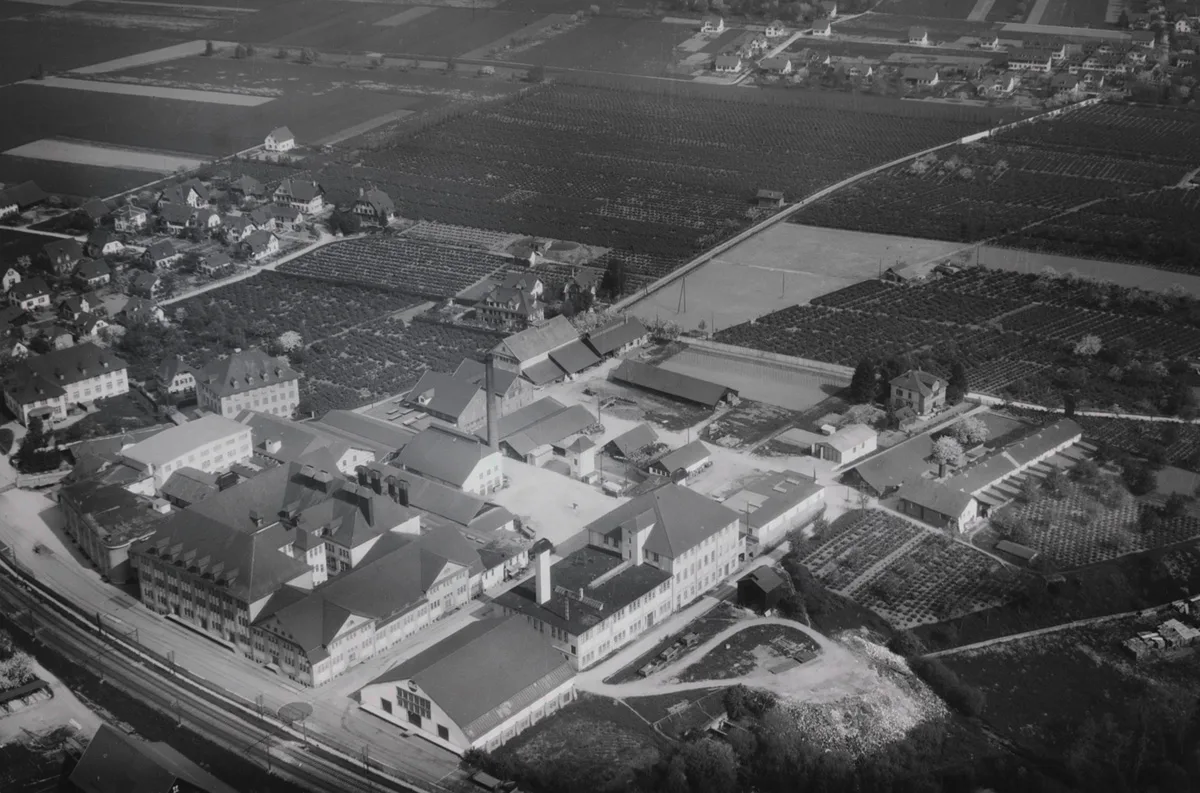

In the emerging post-war consumer society, the canning industry’s sales declined accordingly. Many tinned food manufacturers in Switzerland had to stop production. To stay competitive and set themselves apart from their rivals, manufacturing companies had to adapt to modern consumer needs. Key changes were made, both in the product ranges and in the way they were marketed.

Preserved fruit and values

The success of this home heat sterilisation method was attributed to housewives. Heinrich Oswald, who later became director at Knorr Foods AG, wrote a piece in the Frauenblatt on 22 November 1963 about the guilt that housewives would feel if they used convenience foods such as tin cans in their households.

Still, the behavioural researchers see this shift in consumption as being driven by ‘bad conscience’ on the part of housewives, who deep down feel duty bound to prepare homemade meals rather than simply putting convenience foods on the table.

According to the 1950s advertisements, Frau Erika embodied the perfect housewife. She devotedly cared for her husband and children and always looked immaculate. Using canned foods made Erika a better and more modern housewife. Thanks to canning technology, she was always ready for unannounced visitors – ultimately, she could rely on tinned foods to be able to whip up a tasty meal in minutes. Using canned foods also saved Erika time, which she could devote to other household tasks instead.

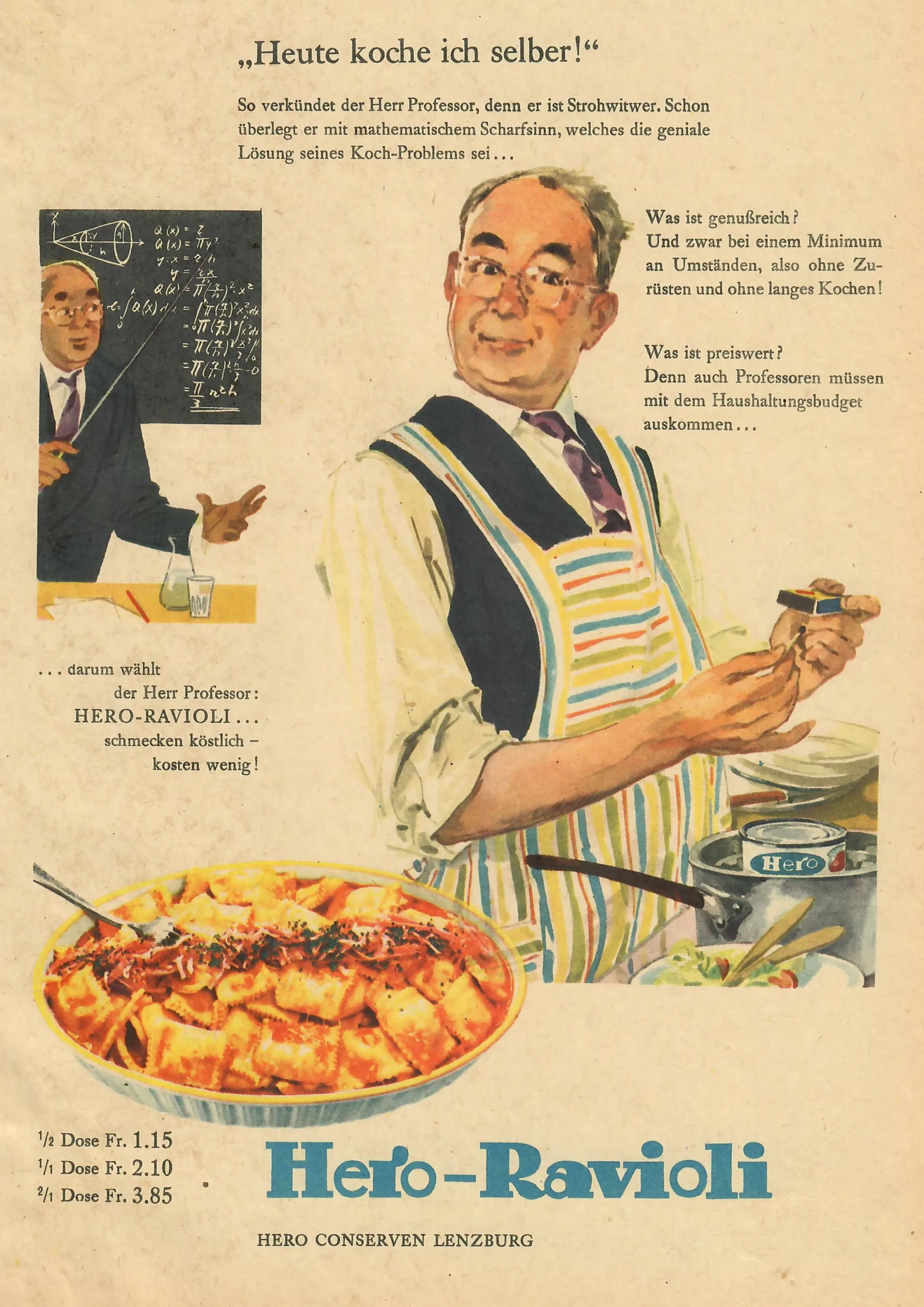

In the 1950s, household purchasing decisions were primarily made by women. Meal preparation was also traditionally a woman’s task. Nevertheless, Hero was keen to expand its customer base to include people with little to no experience in the kitchen. The ravioli ad campaign from 1956 therefore specifically targeted a new consumer group: people to whom the convenience aspect would appeal.

The Italian holiday straight from a tin

Yet Hero’s breakthrough in foreign tinned foods in the 1950s didn’t come from pineapple, but from ravioli. The canning manufacturer had ravioli in its range from as early as 1948. It only became a top seller, however, in the mid-1950s when it was marketed as an Italian speciality. This was linked to the fact that from 1950 a growing number of Swiss people could afford to go on holiday to neighbouring Italy. And they associated their holiday memories with Italian food.

Hero’s tinned foods and the way they were marketed thus represented a new consumer society in the 1950s. From convenient military commodity to a symbol of modern and fast meal preparation, the tin can has always reflected the needs and ideals of the time. Over the years this has ranged from the role of the housewife and men’s cooking skills (or lack thereof), to emerging prosperity and the Swiss people’s growing taste for travel and holidays. The tin can is therefore more than just a receptacle for preserving – it is a mirror of social change.