Swiss monster hunters

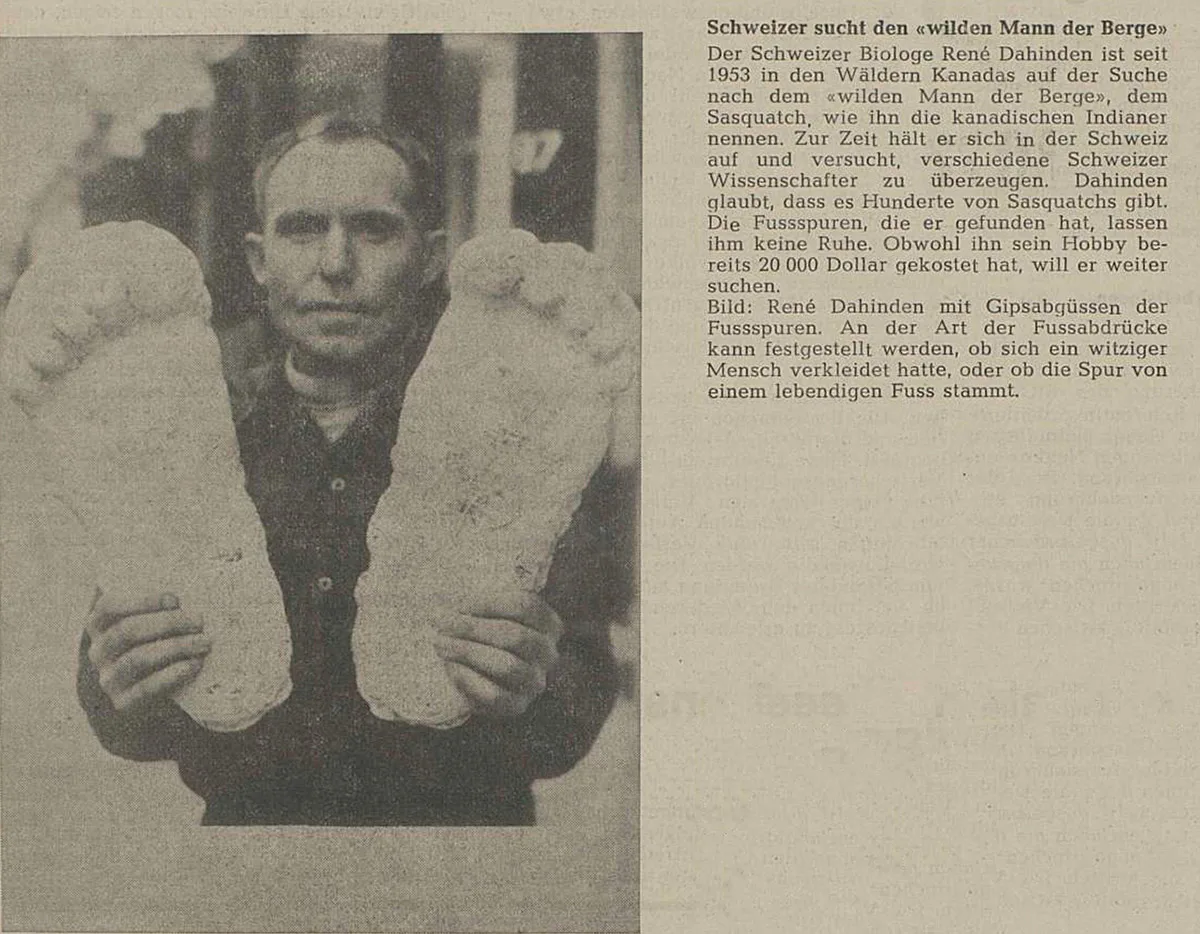

What do an orphan from Lucerne and a geologist from Western Switzerland have in common? A fascination with mysterious creatures. René Dahinden and François de Loys both made a name for themselves in the field of cryptozoology.

To Canada via Sweden

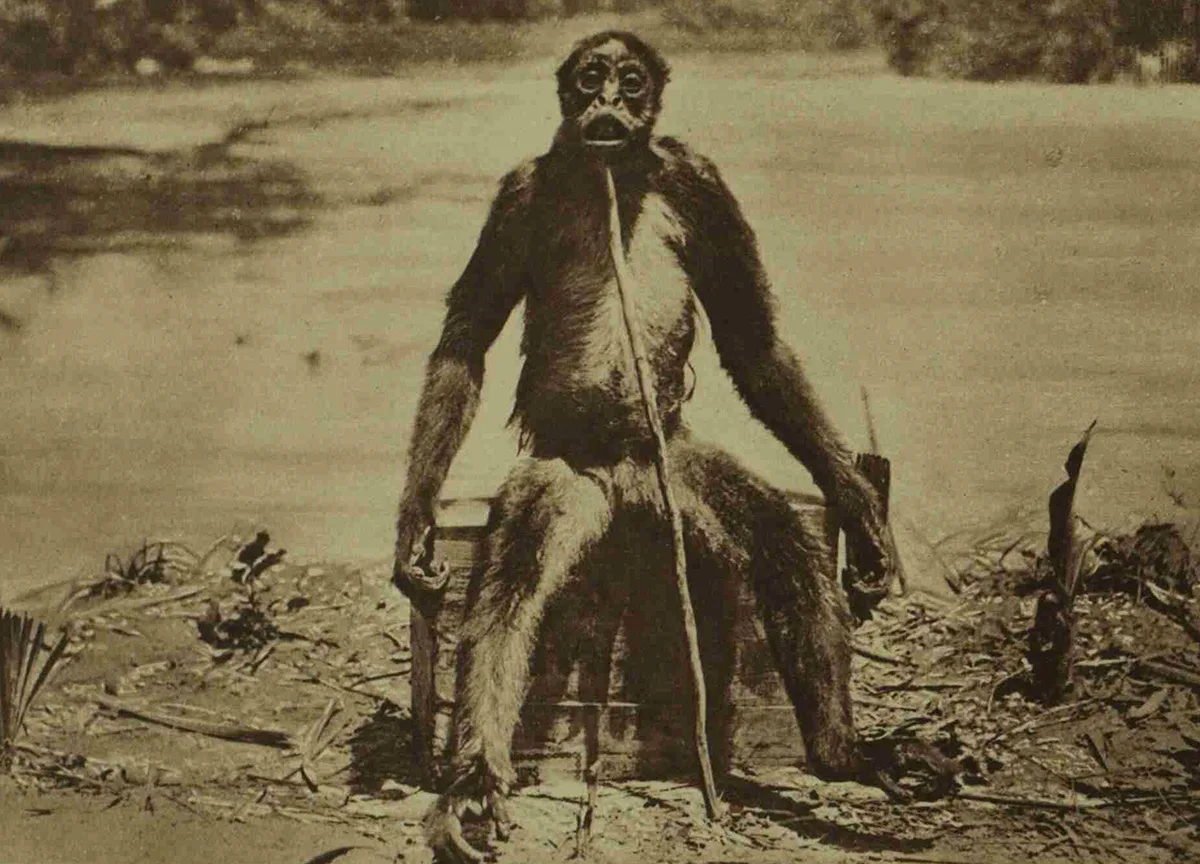

Expedition in Venezuela