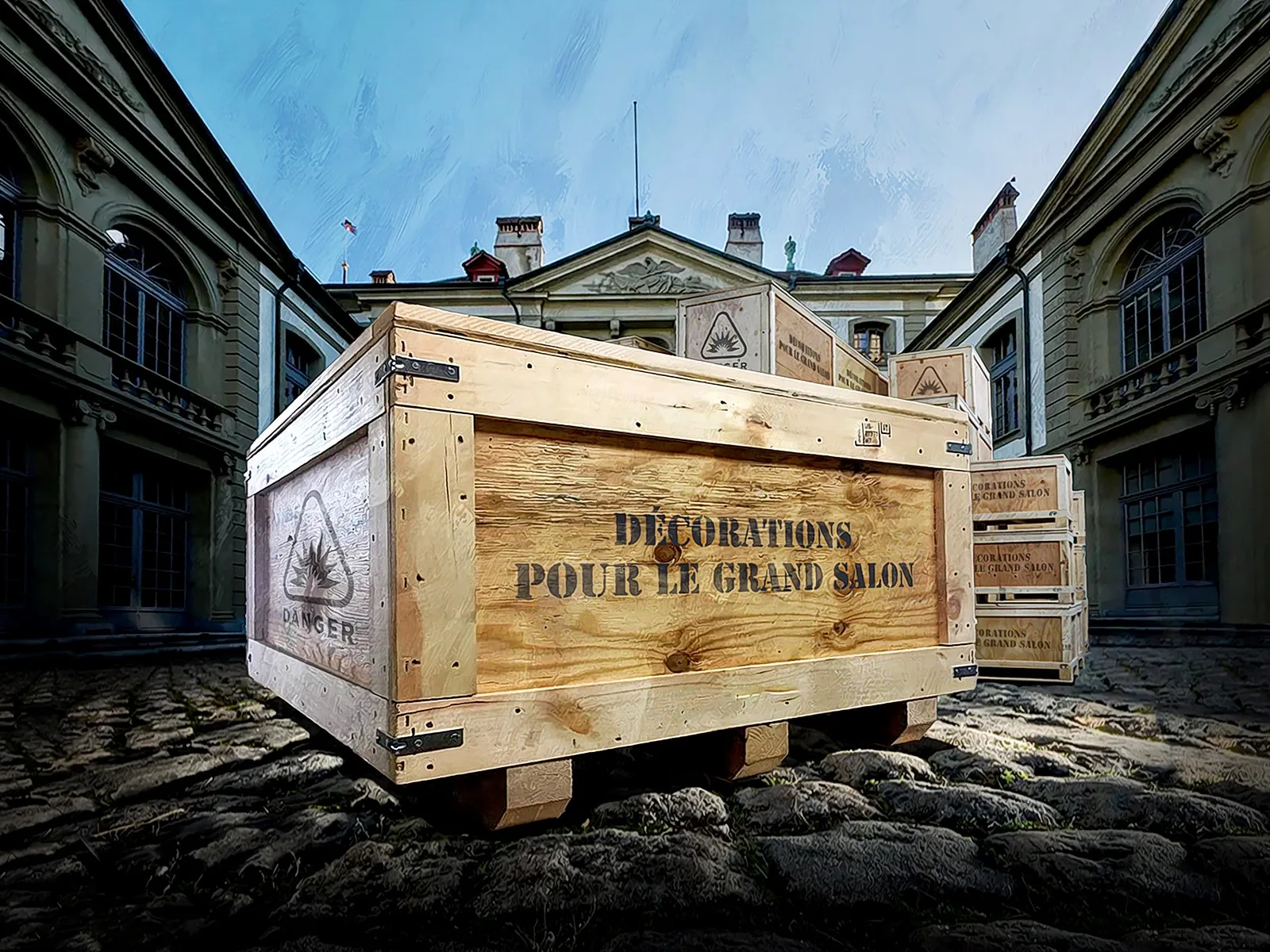

The Erlacherhof plot

From rebellious patricians and ammunition stashed in the city hall to a wave of arrests and a controversial trial – the Erlacherhof plot of 1832 was a turning point in the history of the canton of Bern.

Political power shift

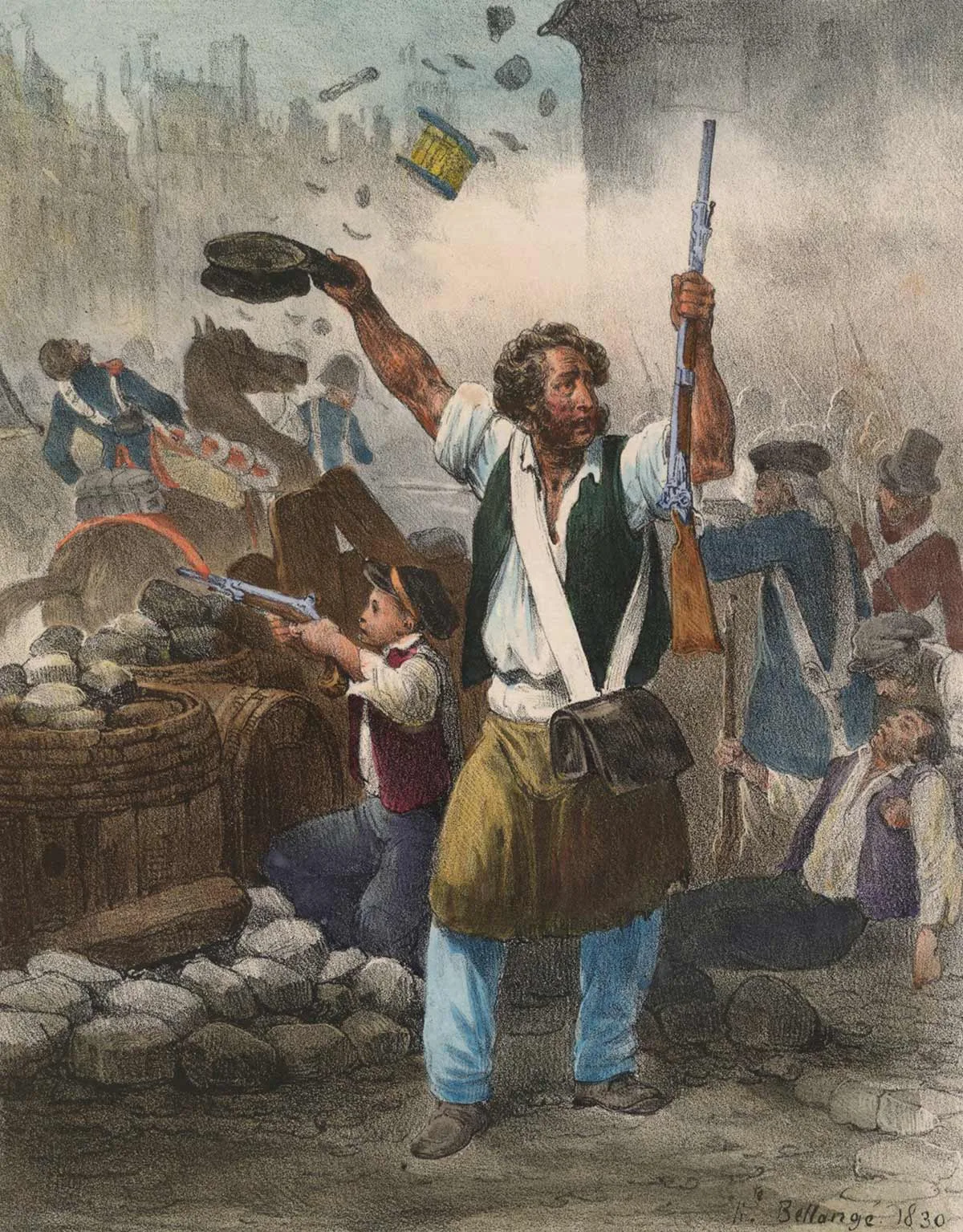

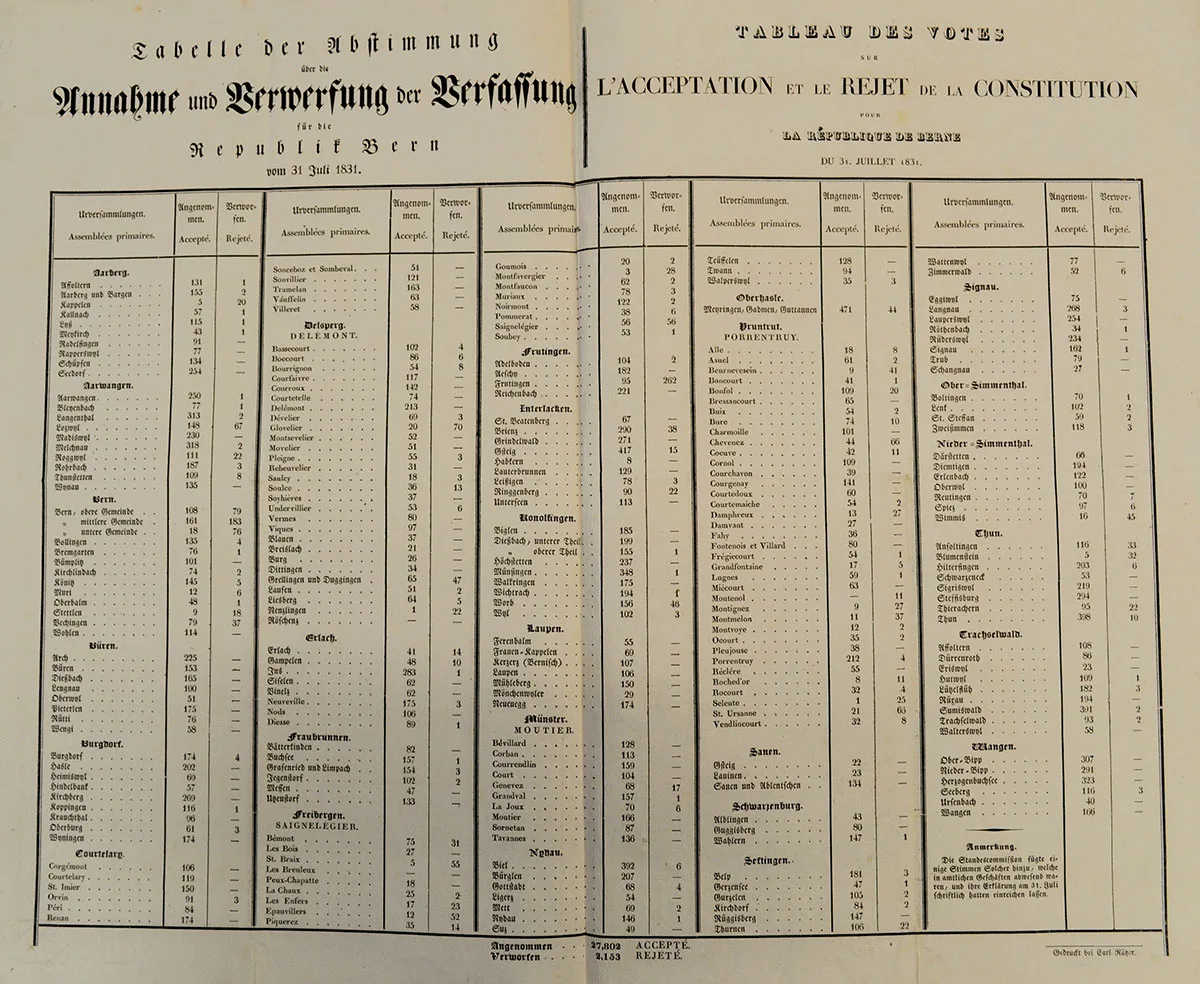

In the 1830s, a liberal constitution led to a power shift in the cantons, with communes now giving voting rights to all citizens rather than merely to a privileged class. This resulted in the urban elites losing control of their territories. This was also the case in Bern, where electoral communes sprang up throughout the canton. Yet the old elites fought to retain the old order and thus their power and wealth. This led to a division, which still exists today.