Series: Book Printing in Europe

Johannes Froben was a star in the middle Ages. One of his customers was Erasmus of Rotterdam.

In 1470, printing was in progress in sixteen European cities. That number rose to eighty-one by 1480 and to ninety-eight by 1490, before dwindling to seventy-five in 1500. All told, printing operations were established at 261 locations in the fifteenth century. Some remained active only briefly, due not least of all to the substantial investments in material and wages required to print, sell, and (ideally) turn a profit on a single publication. In various cities, especially the major commercial centers, numerous printing shops operated concurrently, as was the case in Cologne and Venice, for example, where more than thirty (Cologne) and 200 (Venice) firms, respectively, were active during the fifteenth century.

Of the total number of incunabula published, 36.4 percent were printed in Italy, 33.6 percent in the German-speaking region, 17.5 percent in France, 7.4 percent in Belgium and the Netherlands, 3.7 on the Iberian Peninsula, and 1.4 percent in England. The most important printing centers, which accounted for three-fifths of all published incunabula, were:

- Venice 3705

- Paris 3026

- Rome 2021

- Cologne 1531

- Lyon 1334

- Leipzig 1210

- Strasbourg 1121

- Milan 1106

- Augsburg 1073

One-seventh of all incunabula were printed in Venice alone, and another one-third in Venice, Paris, and Rome. If we add Nuremberg (926), Florence (863), and Basel (764) to the cities listed above, the total comes to twelve printing centers that accounted for two-thirds of the total number of incunabula produced.

Eighty percent of all works were published in Latin. Despite the widespread interest in the humanities, only sixty-five incunabula were published in ancient Greek, many of them (i.e., 27) in Venice. The other thirtyeight, with one exception, were printed in the following cities: Florence (13), Milan (10), Vicenza (7), and Reggio Emilia (3), and Brescia, Modena, Parma, Rome, and Paris (one each). Astonishingly, 175 Hebrew incunabula have been identified as well, which were mainly printed in the Italian cities of Soncino (29) and Naples (27 or 28). Vernacular publications accounted for a majority of printed works only in Augsburg and Florence. Augsburg became the leading book-printing center in the fifteenth century and remained so for the next two centuries. The share of German books printed there rose to over seventy percent between 1479 and 1500. Florence accounted for seventy-nine percent of all Italian incunabula (679 of a total of 863). More than one-seventh of these (105) were works by Girolamo Savonarola. It was he, and not Martin Luther, who fueled the first public controversy with the aid of the printing press, although the new medium of thin, cheap circulars was established above all during the German Peasants’ War and the Reformation.

Disillusion and Consolidation

The problem facing early printers was that, having invested heavily in purchases of printing presses, composers’ utensils, and paper, in addition to wages, they urgently needed strong volume sales and revenues to break even. Manuscripts were often produced on commission, whereas hundreds of thousands of print products were produced for as-yet-unknown buyers who first had to be informed about the publication of a book and then given an opportunity to purchase it. Financially speaking, the printing business required considerable patience, which often wore thin, especially among smaller printing firms. Certain best sellers promised reliable earnings, although printers were well advised to avoid overproduction of the kind that occurred in Venice in 1472, unleashing a crisis in the local printing trade. Printers coordinated their production with each other in some cases, or closely monitored the program of offerings at the Frankfurt book fair in hopes of discovering possible unoccupied niches. Certain centers specializing in specific market segments also emerged. In Florence, for instance, very few works by ancient authors were printed, since that market was dominated by Venice. But the city on the Arno was known for its Italian publications, just as Augsburg was for German works. A similar division of labor is also recognizable between Basel and Zurich in the sixteenth century. Basel’s strengths lay in the field of Greek and Roman Antiquity and in Humanism, medicine, and books published in Hebrew. Zurich specialized in the German Bible, reformed theology,

and various school textbooks.

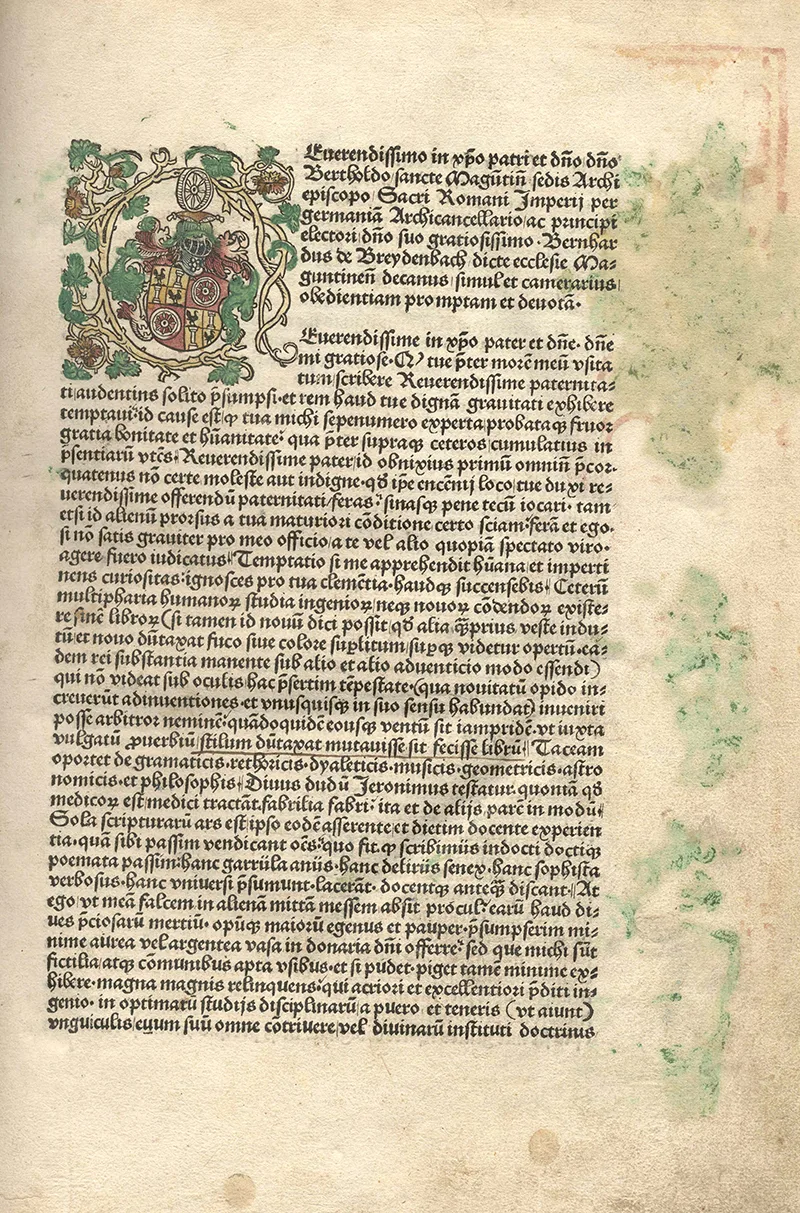

Incunabula "sanctae peregrinationes" produced by Bernhard von Breydenbach, Mainz 1486. Photo: Wikimedia

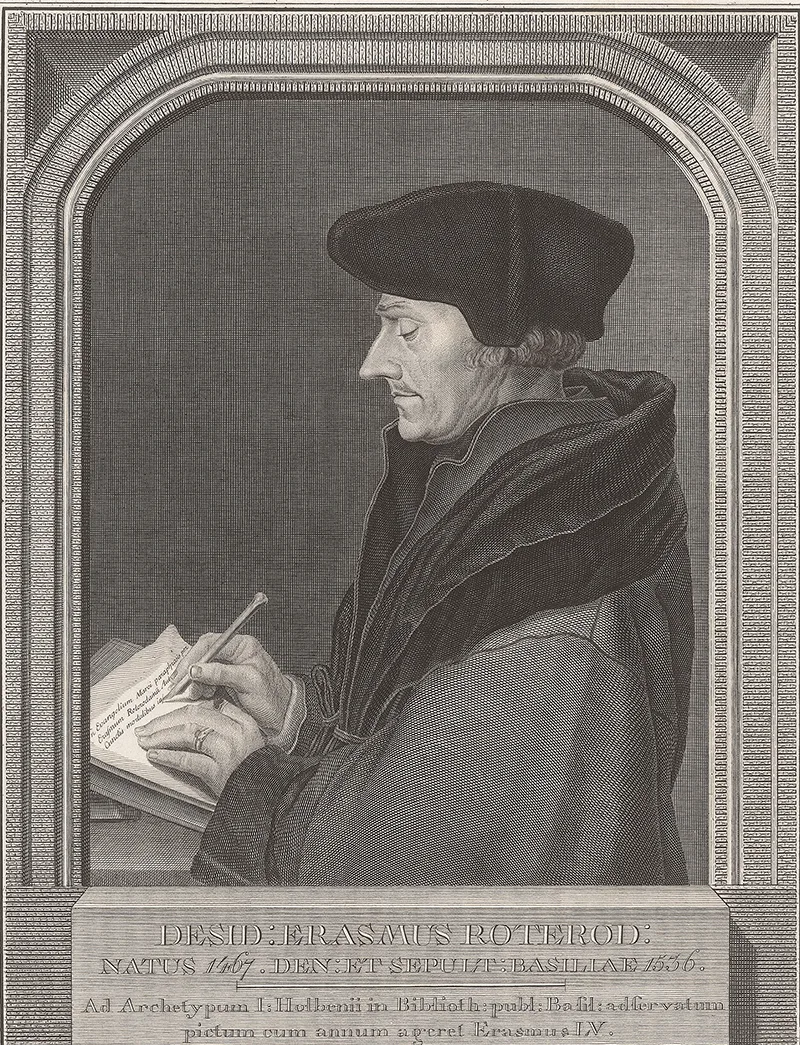

Erasmus of Rotterdam, copperplate of 1795. Photo: Swiss National Museum

BBC broadcast about Esiderius Erasmus.

This bible was published by Erasmus of Rotterdam and printed by Johannes Froben in 1519 in Basel, Switzerland. Photo: Swiss National Museum

It was a no lesser figure than Erasmus of Rotterdam who, in his Adagia (1st ed. pub. 1500), sang a song of praise under the heading “Festina lente” (make haste slowly) to the two Humanist printers Aldus Manutius of Venice and Johannes Froben of Basel, both of whom had accomplished a great deal through their efforts to promote the literature of Classical Antiquity: What Aldus set in motion in Italy — for he passed away, while his successors continue to profit from the fine reputation associated with his name even today — is now being pursued north of the Alps by Johannes Froben with no less fervor than Aldus and by no means unsuccessfully, although, as no one can deny, with much less profit.

Froben not only specialized in the literature of Classical Antiquity, he also became Erasmus’ house printer. The Friesian scholar Wigle fen Aytta fen Swigchem (Vigilius ab Aytta Zuichemus), who was staying in Basel in 1533 saw that as the reason why Froben gained recognition beyond the borders of his own country. Regardless of whether Froben’s name stood for Classical authors or for Erasmus, or both, there can be no doubt that the retention of the program of printed works for years on end supports the conclusion that correspondingly large numbers of the titles in question were produced. The demand for those books remained more or less stable, and the printers of long sellers claimed that field and those authors to a certain extent as their own property, from which good money could be earned. The substantial editions, some of which were published in several thousand copies thus ensuring sales over an extended period of time, required sufficient storage space, which was not always readily available or affordable, as indicated, for example, in correspondence with the printer Johannes Oporinus of Basel.

The famous book-printing centers in the age of incunabula, including Augsburg, Basel, Cologne, Lyon, Paris, and Venice, maintained their leading roles in the book business. Newcomers to the group were Wittenberg and Geneva, the cities in which the Reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin did most of their work and were most often published. Antwerp rose to the status of a commercial metropolis, as reflected in book production as well, and London dominated the growing English market. Following the bloody Spanish occupation of the Southern Netherlands, various printers escaped from Antwerp to the freer north in 1585 and made Amsterdam the new book-printing center, which would later come to full bloom in the seventeenth century.

The prices of the books and the first bestseller.

Read part 4: