The Battle on the Planta

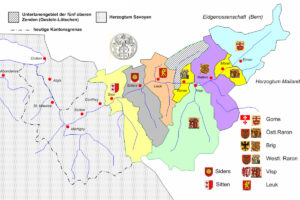

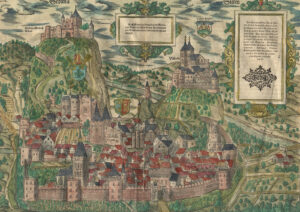

The Valaisans and their Swiss allies defeated a powerful Savoyard army on November 13, 1475 just beyond the gates of Sion. Though little-known outside of Valais today, the Battle on the Planta was of resounding importance to Valais, Savoy, the Old Swiss Confederation, and Burgundy. Had the Valaisans and their Swiss allies lost the battle, Valais and the Confederation would have found themselves at the mercy of Savoy and Burgundy at the height of the Burgundian Wars.

International Tensions Boil Over

The Battle on the Planta

…know that we will not forget it. We announce this to you in the hope that you will rejoice greatly with us in our good fortune as we do with you.