“Coffee from Helvécia”

Surprising insights into Switzerland’s colonial history at the Johann Jacobs Museum in Zurich.

A dining table with spotless white damask, fine porcelain, crystal, silver. Starched napkins, flowers, chandelier. After dinner, the men withdraw to the study or library with their cigars. The ladies sip their cups of mocha in the adjacent winter garden.

That is roughly how we picture the lives of refined society during the Belle Epoque, thanks to television. And this inevitably springs to mind when one enters the central salon on the ground floor of the Johann Jacobs Museum on Utoquai quay in Zurich. Admittedly, the Wilhelminian style villa, which dates from 1913 and previously housed the Jacobs Coffee Museum, has been given a facelift by the well-known architectural firm Miller Maranta: representative with a touch of irony. How else should one interpret lampshades that resemble boxer shorts?

But the expansive dining table, especially, with its white tablecloth embroidered at the edges seems like a relic from an era in which women journeyed through life with a dowry chest. Though appearances can be deceptive. Contrary to expectations, there are no flowers or initials here weaving their way along the edge, but lists of names and numbers in the beautifully curved script of historical registers. Emblazoned alongside is an official seal with the Swiss cross. “Agence Consulaire Suisse Léopoldine,” it says in the most exquisite St. Gallen eyelet embroidery.

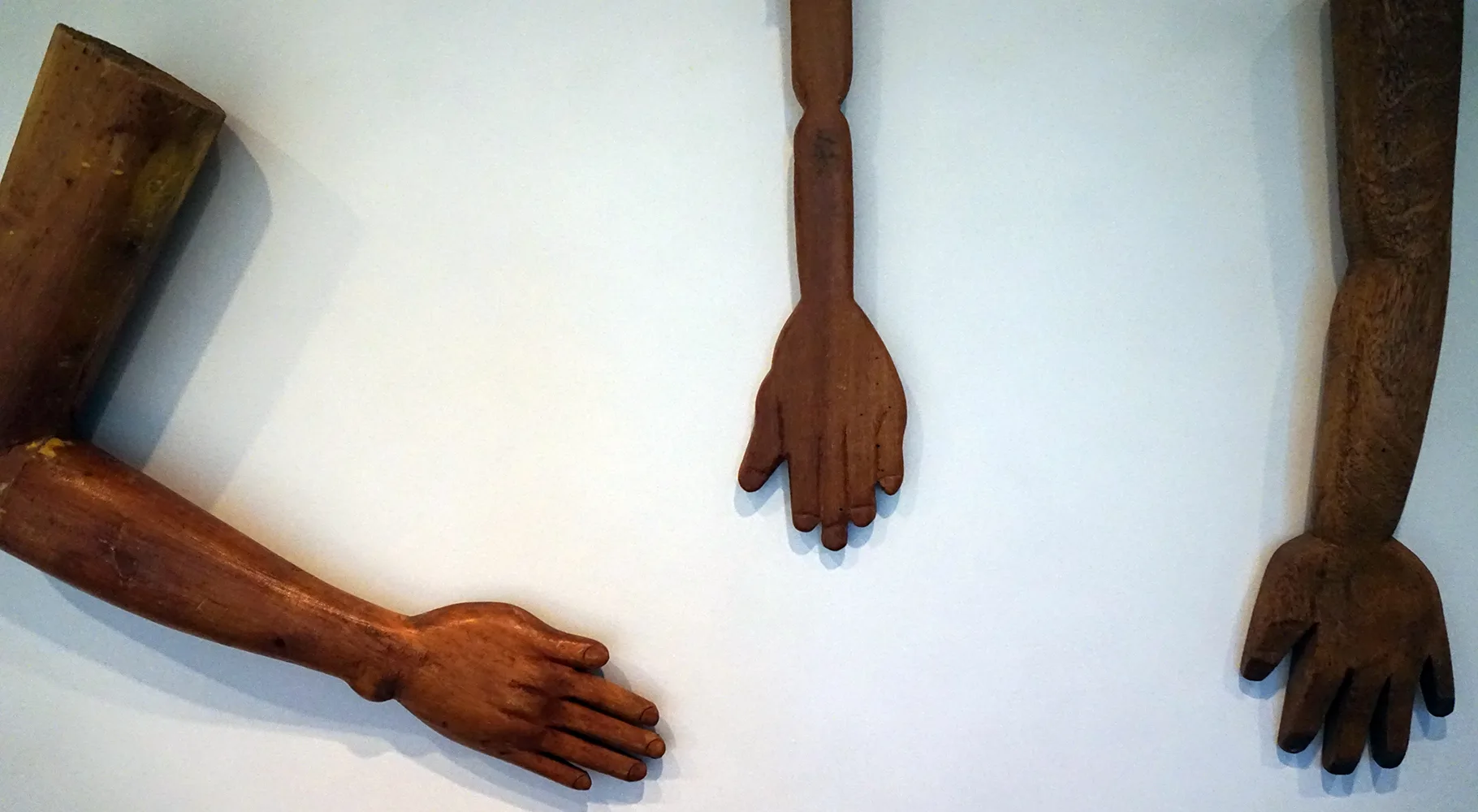

Series of votive offerings or ex-votos donated to the Church out of gratitude. Wood, different dimensions, late 19th century. Photo: Johann Jacobs Museum

Never heard of Leopoldina? That’s hardly surprising as we are talking here about a chapter in Swiss colonial history that is not quite as spotless as the tablecloth. Swiss colonial history? Yes, Switzerland has one too, though we are only very slowly coming to terms with its existence as well as the need to deal with it. This exhibition is a contribution towards that effort.

The tablecloth was produced by Denise Bertschi, a Swiss artist born in 1983, and goes to the heart of the Leopoldina colony. It was founded in 1818 in Bahia (Brazil) by Germans and Swiss who wanted to escape the poverty that existed back then in their homeland. Leopoldina soon developed into one of the world’s largest coffee plantations. This was only possible because the colonial masters had access to cheap black slaves. Even after slavery was officially abolished in Brazil in 1888, these people were often still economically dependent on their former owners. The names on the tablecloth are those of Swiss slaveholders. The numbers after them indicate the number of their slaves.

«Bem vindo a Helvécia», Denise Bertschi, 2017

Denise Bertschi also leads us directly to the scene, a place now called Helvécia which is an officially recognised “Quilombola”, a settlement of former slaves. In one of the two video installations, we accompany descendants of the once slaves to the overgrown, almost forgotten cemetery of Leopoldina; in the other we are confronted with their verbal testimonies passed down from generation to generation. These stories tarnish the picture painted by the rare historical sources and reports. The latter seem mainly designed to portray the colonisers and traders as luminaries and messengers of civilisation. The violence meted out is considered a necessary evil. The exploitation is glossed over.

An idealised, idyllically orderly Leopoldina is also presented to us in contemporary watercolours and the abstract from a travelogue by Johann Jakob von Tschudi in 1866. Tschudi speaks plainly about the importance of slavery to the success of the colony. The slaves, he says, “generally” enjoyed “humane treatment”. We see what that meant a few steps further on, where instruments to punish slaves are exhibited, such as a wrought iron muzzle.

An ensemble of black dolls from the 20th century are a reminder of the ambivalent relationship between Europeans and black slaves. One of these dolls, which used to be called “Negerbäbis” (Negro babies), wears a lavish christening gown in St. Gallen eyelet embroidery. The Swiss not only exported the coffee from Leopoldina to Europe, which was coveted because of its excellent quality. They also imported into Brazil their religion and their embroidery machines. Eyelet embroidery remains popular in the region to this day.

In the background a doll with christening gown in St. Gallen eyelet embroidery. Photo: Johann Jacobs Museum

Other exhibits also have a connection with the present. One particularly curious exhibit is the photo archive of a certain Flavio de Carvalho, who tried to found the modernist “Leopoldina Republic” in the late 1930s. Unfortunately there is scant explanation to go with the archive. A contemporary touch is provided by several works of art influenced by tribal cultures and a hand-made coffee cart like those which are still used by street vendors in Bahia today.

Anyone expecting an overview of the history of Leopoldina will be disappointed as this history is not available yet. The exhibition can be seen as a collection of evidence that aims to lay down the first tracks and stimulate further questions.

It is part of a new museum concept which the curator, Roger M. Buergel, who also once managed a “documenta” exhibition in 2008, has been pursuing since he began working at the Johann Jacobs Museum in 2014. He uses cases studies to present art history and cultural history topics here which may at first seem quite quirky. But for regular visitors to the museum, what is emerging is a radically new conception of art history as post-colonial art history.

The Johann Jacobs Museum illustrates, in an exemplary fashion, how interesting, even controversial questions can be posed with pocket-sized exhibitions. The stale air of the former “Coffee Museum”, with the only reminder of this being a decorative wall frieze of historical utensils, is gone. This is all the more striking since the founding family, the Jacobs, made their wealth from coffee, the commodity associated more than almost any other with a long history of unfair working conditions.