A new view of the world

Every era has its mass media. In the 18th century, the peep box with its coloured views of distant lands enjoyed huge popularity. This was the start of the development of modern visual media.

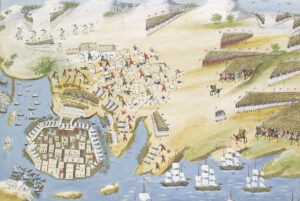

In the 18th century, travel became fashionable. But it was expensive and dangerous. Those who stayed at home read travelogues, looked at engravings, or peeked inside peep boxes at colour pictures of Saint Petersburg and Rome, of Berlin and Paris, of the theatre fire in Amsterdam, of the earthquake in Lisbon, of the capture of New York by British troops in the American War of Independence or of marvels of nature such as the Rhine Falls. The pictures appearing in the box opened up the world and shaped people’s view of it.

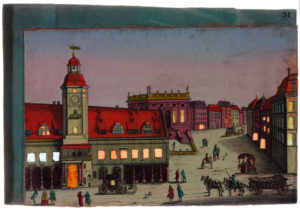

Peep-box card. The Fontanka in the imperial garden in Saint Petersburg. Augsburg: Jos. Carmine, around 1790. Coloured etching. Image: Swiss National Museum

Peep-box card. Invasion of New York by English troops. Augsburg: Académie Impériale, 1776. Image: Swiss National Museum

The colour television of the 18th century

The peep box could be found in marketplaces and also, in a smaller size, inside inns. One such peep box made of cardboard, with a set of corresponding peep-box cards, can be found in the collection belonging to the Swiss National Museum. The “colour television of the 18th century” used lenses and mirrors to create the illusion of spatial depth. Its colour pictures with their mirror-image titles realistically reported on far-off cities and countries, current events and disasters. Sophisticated candle lighting made it possible to imitate the alternation between day and night. Windows, doors and stars were often cut out on the cards for this purpose and backed with coloured silk ribbons. In this age of electronic media, it is almost impossible for us to imagine now the immediate impact of peering into the box while listening to the commentary of the peep-box man.

Zurich in the peep box

Most of the cards showed views of famous cities: Saint Petersburg, Vienna, Antwerp and Geneva, but also Constance, Meersburg, Lindau and Schaffhausen. Another famous city in the 18th century was Zurich. The two Zurich cards from the “Académie Impériale” publishing house in Augsburg depict the most popular views of the city: the one from the lake and the famous view from the Schwert inn across the Limmat River and the lake to the Alps. A stay in a corner room of that renowned inn with this view which was extolled everywhere in the travel literature was a must on any Swiss trip. Everyone who was anyone stopped at the “Schwert”: from Casanova to the Duchess of Württemberg to Goethe. The names of the guests of the Schwert hotel were written on the registration forms of that time, and their stay was announced to an interested public in advertisements in the “Donnstags-Nachrichten” newspaper.

Incidentally, in his memoirs Casanova reported on the amorous adventures in the “Schwert” which led to his decision to become a monk at Einsiedeln Abbey. Hermann Hesse retold the story, a good 110 years after it had been written, under the title of “Casanova’s Conversion”.

Peep-box card with a view of Zurich. View from the Schwert hotel of the Limmat River and lake. Augsburg: Académie Impériale, 1770–1795. Coloured etching. Image: Swiss National Museum

Peep-box card with a view of Zurich. “View of the city of Zurich / taken from the lakeside”. Augsburg: Académie Impériale, 1770–1795. Coloured etching. Image: Swiss National Museum