The bogus Doctor Meyer

The biography of Johann Jakob Meyer from Zurich reads like an adventure novel: womaniser, confidence trickster, and up to his eyeballs in debt. How could such a man become a Greek hero?

We are facing our final hour. It makes me proud to think that the blood of a Swiss man, a descendant of William Tell, will mingle with the blood of the heroes of Hellas…’ Johann Jakob Meyer wrote these lines to a friend on 10 April 1826, shortly before he, together with the inhabitants of the Greek port city of Missolonghi, launched a desperate attempt to break through the ranks of the Turkish army besieging the city.

Flashback in time: Johann Jakob Meyer, son of an apothecary, was born in the ‘Haus zur Sichel’ in Zurich’s old town in 1798, the same house where, 11 years later, the writer and politician Gottfried Keller also saw the light of day. His mother died early, and his father soon remarried. Johann Jakob trained as an apothecary. When the family moved out of the city, the young man became ‘self-employed’. At the tender age of 19, he married Salomea Staub, four years his senior. The new husband, however, preferred to spend his free time in the tavern and with other women. Scarcely a year later, the marriage was over. Johann Jakob Meyer didn't seem to care much about this. In 1819, he studied medicine for a short time in Freiburg im Breisgau. However, the bon vivant soon amassed a large mountain of debt and had to flee the city. A corresponding – and unsuccessful – request by the German university to the Swiss authorities to settle these debts was rejected on the grounds that ‘this dissolute person has no assets to his name…’

Suddenly a doctor and a surgeon

When the Greeks rebelled against Ottoman rule in 1821, the apothecary’s son was presented with an excellent opportunity to get out of Switzerland and leave his unpleasant personal situation behind. In Europe there was great solidarity with the Greeks. For many, the Greek cause amounted to nothing less than saving Hellenistic culture from the Ottoman barbarians. Interestingly, it had taken several centuries for Europe to start voicing its indignant outrage, as Greece had been under Ottoman dominion since the fall of Mistras in 1460.

‘Aid societies for Greece’ and ‘Philhellenic associations’ sprang up everywhere. Johann Jakob applied to the local aid society in Bern as a doctor and surgeon and, with the society’s money and good will, travelled south. It was only later that the society realised the man from Zurich was neither a doctor nor a surgeon.

The Swiss con artist arrived in Missolonghi towards the end of 1821. Shortly afterwards he married Altani Inglezou, the daughter of a respected merchant. His father-in-law set up a pharmacy for the ‘doctor’, which Meyer ran with considerable skill. Johann Jakob Meyer converted to the Orthodox faith and quickly learned the Greek language.

From doctor to journalist

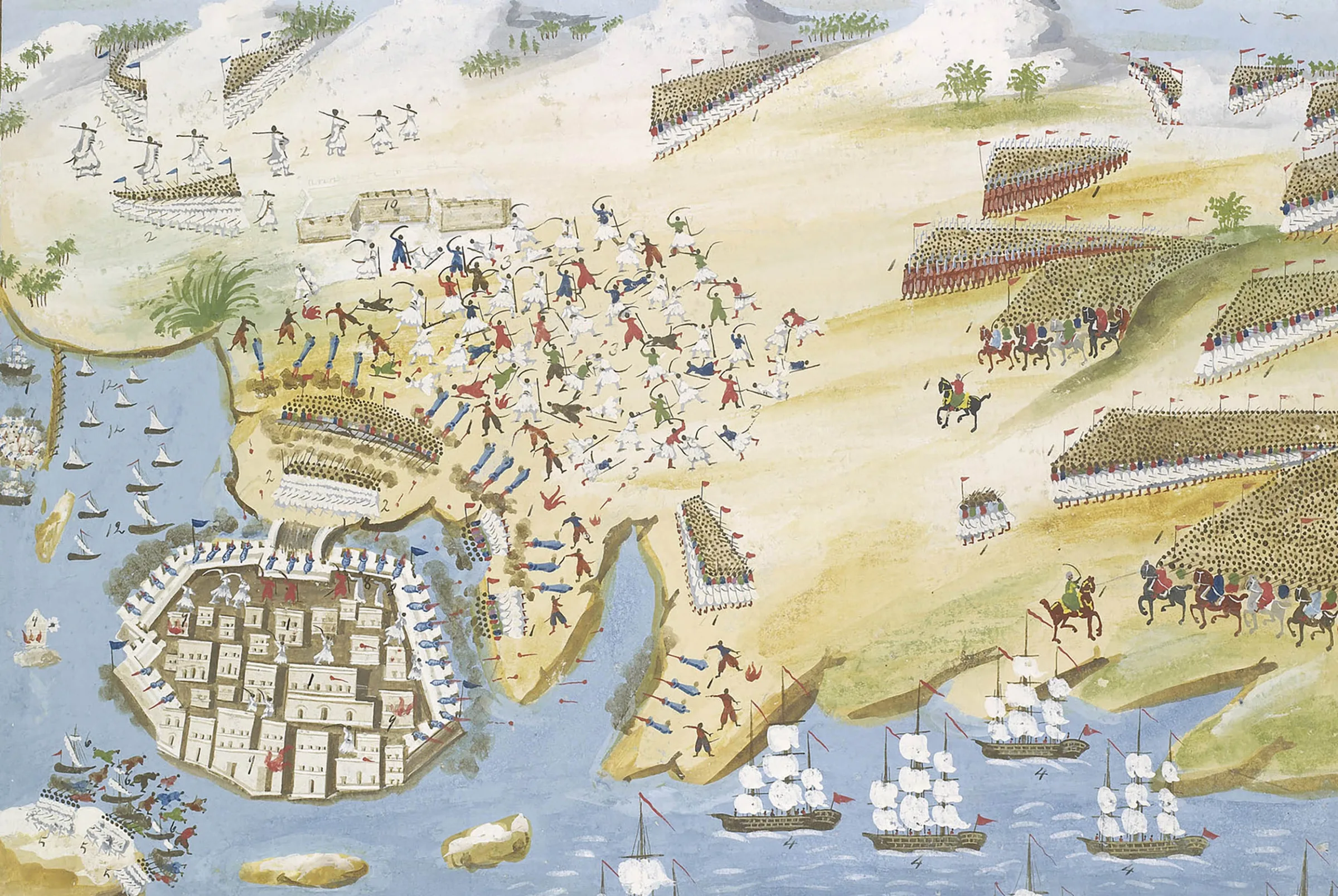

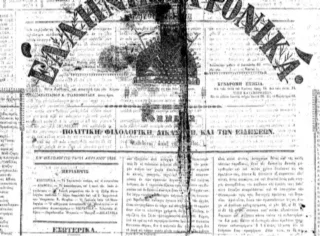

In 1822 the Turkish army positioned itself outside the town and settled into a siege. With its solid port facility, Missolonghi proved difficult to capture. Meyer took over the management of the local hospital. The Greeks successfully repelled several attacks. After a wet winter during which they suffered heavy losses, the Turks finally abandoned the siege. In 1824 Johann Jakob Meyer became editor of the newly founded newspapers Tilegrafos and Ellinika Chronika. His writing style was imaginative and populist, but not everyone liked it.

That same year, a celebrity arrived in Missolonghi in the shape of Lord George Gordon Byron. The English poet had long supported the Greek resistance financially and in his literary works, and in the eyes of the Greek people Byron was a hero. Byron had a low opinion of Meyer’s literary outpourings, however. A rivalry developed between the two men.

In 1825 the Ottomans blockaded the port of Missolonghi again. The Greeks rejected the offered truce. Johann Jakob Meyer, now a father of two, shut down his newspapers at the beginning of 1826. The printing press had become a casualty of the Ottoman bombardment. In April the besieged inhabitants attempted to break out. The plan failed, and the 20,000-strong Ottoman army unleashed a bloodbath.

And what happened to Johann Jakob Meyer? It is not known whether he died in the hail of Ottoman bullets, or blew himself up with the rest of the inhabitants who remained behind. While the ‘Doctor of Missolonghi’ is revered as a hero in Greece to this day, the Swiss gentleman is still a historic lightweight in his home country, and is only ever mentioned when the talk turns to imposters and high-class swindlery.