When Aarau became the capital city

Over 220 years ago, Aarau was the political centre of Switzerland. The euphoria was huge, but Aarau retained its status as the capital city for only around five months.

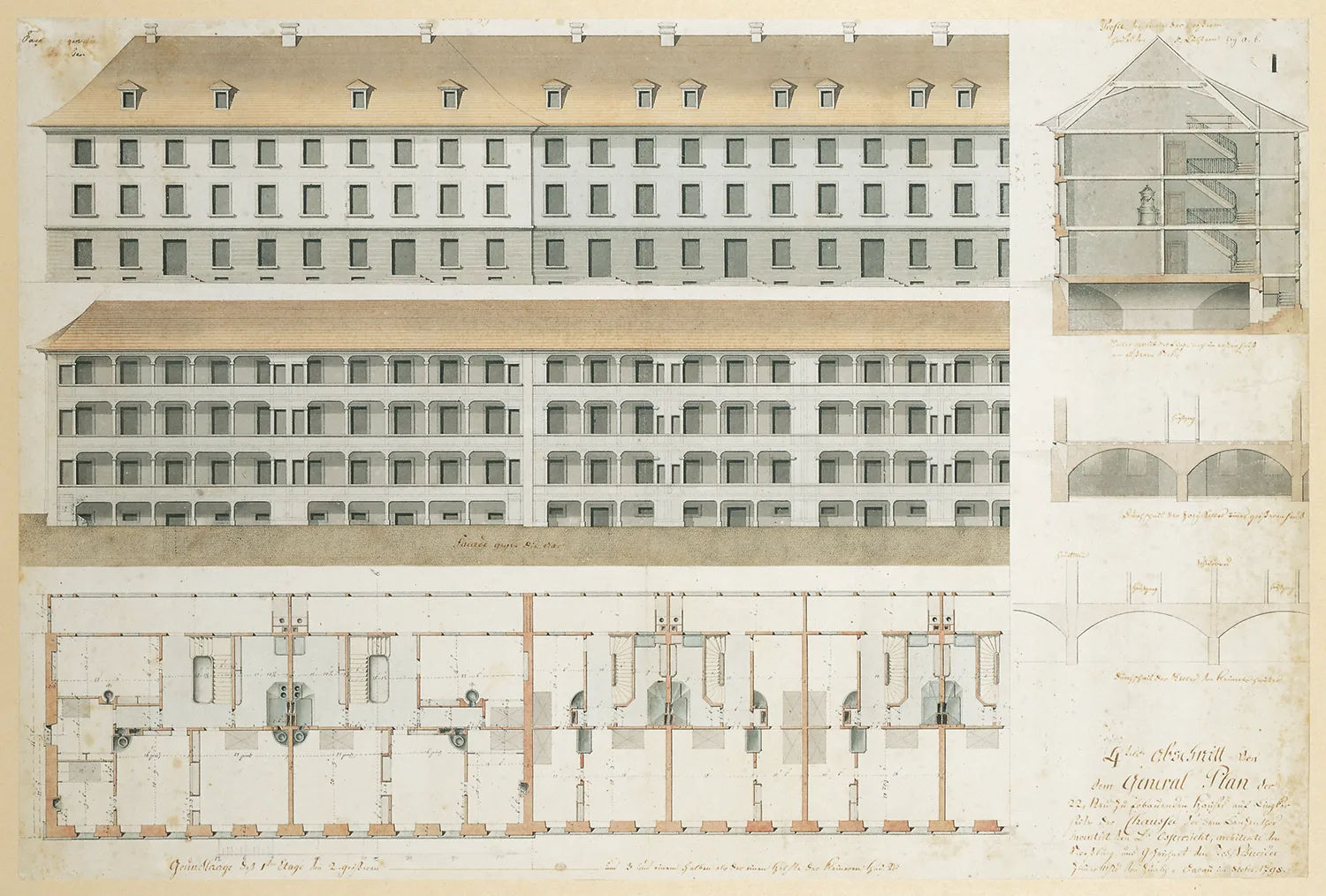

The Helvetic Republic is highly controversial in Swiss cultural memory. Even just the thought of this era is enough to make people shudder in many cantons and their capitals, while it leaves others cold. In Aarau, on the other hand, this period in which the Old Swiss Confederacy collapsed is seen as a high point in the city’s history. These days, if you take a guided tour of Aargau’s capital, wherever you go you will hear all about episodes of this interlude that was the Helvetic Republic…

In 1798, Aarau found itself in an extraordinary whirl of events. In January, the envoys of the Swiss cantons met in this city on the Aare for their very last “Tagsatzung”, or Legislative Assembly, to reaffirm their old ties in the face of the impending French invasion. But no sooner had these envoys left Aarau at the end of January than this town which up until that point had been an obedient subject of Berne attempted an uprising. The citizens proclaimed their independence from Berne and as early as 1 February they danced around a hastily constructed tree of freedom. The arrival of troops from Berne managed to quell the desire for freedom once again, but only briefly, namely until the end of the Old Swiss Confederacy after the French victory in the Battle of Grauholz on 5 March.

The delegates of the pro-revolution cantons agreed to meet again in Aarau in early April to found a “Helvetic Republic” based on the French model. This cast the spotlight of revolutionary activities on the small city, which had only 2,500 inhabitants back then. As early as 4 April, Aarau was named as the provisional capital city. What was the reason for this unexpected honour? The atmosphere! The vast majority of the citizens had been longing for liberation; the educated and relatively well-off people of Aarau sensed their chance to free themselves of the patriarchal rule of the “Gnädige Herren”, or Gracious Lords, once and for all and to have an influence in federal politics in line with their status. Up until that point the political and economic careers of the people of Aarau had ended at the city boundary. With the coloured fabric cockade on their hats they threw themselves into the experiment in democracy.

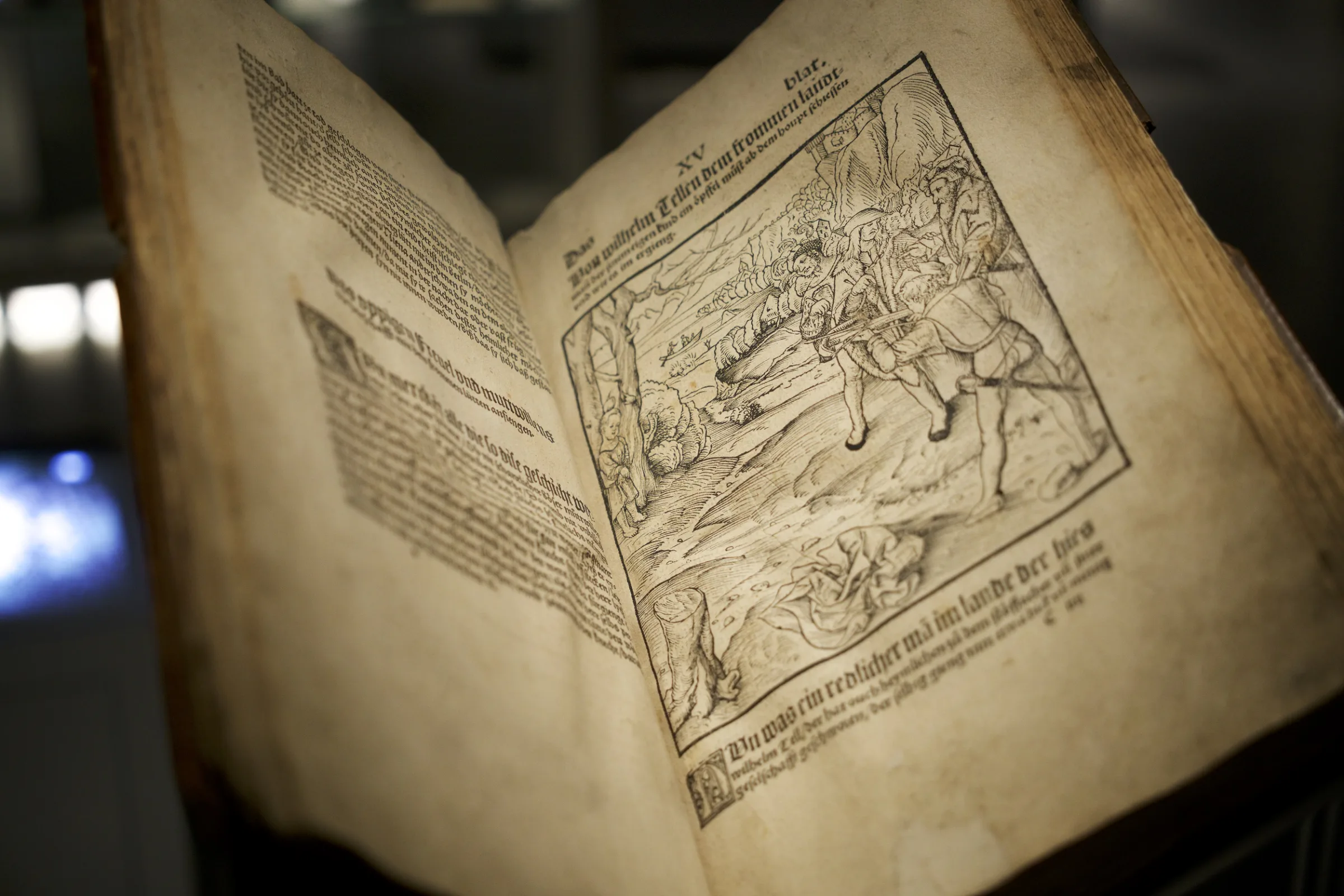

Role model for Aarau: Tree of freedom on Münsterplatz square in Basel on 22 January 1798. Image: Swiss National Museum

Helvetic Republic hat with brim turned upwards and green/red/yellow cockade. Image: Swiss National Museum

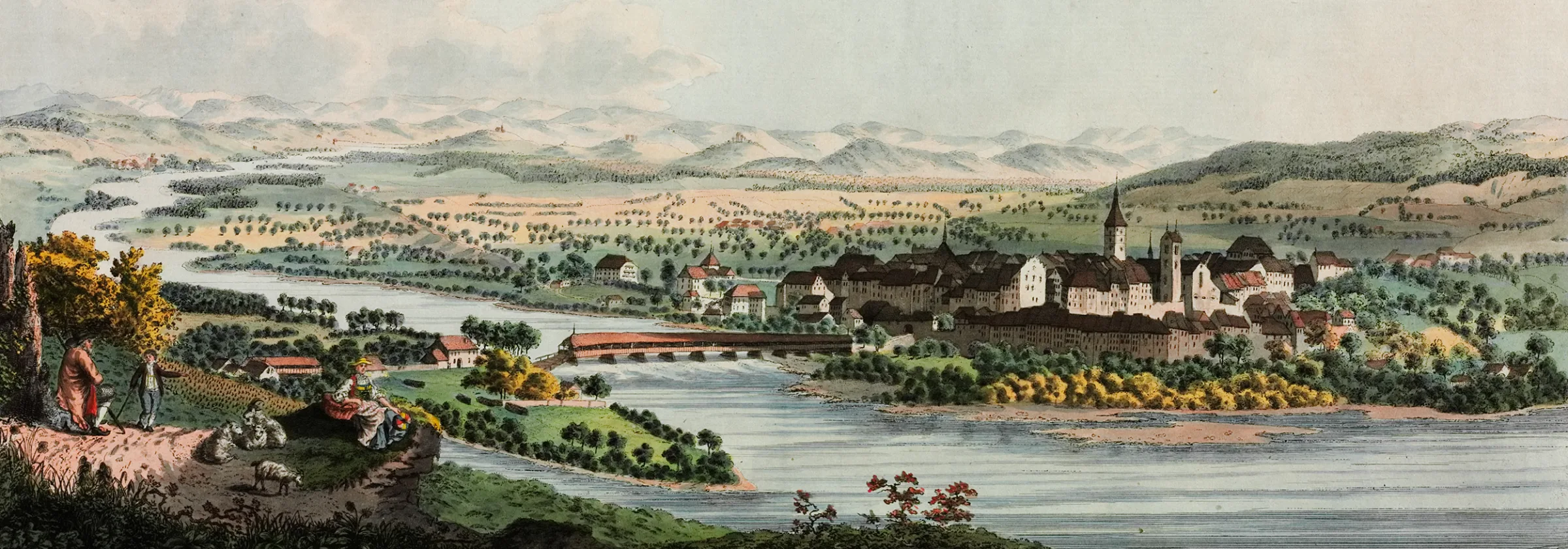

The National Assembly of the Helvetic Republic at its first session on 12 April 1798 in Aarau City Hall. Image: Aarau City Museum

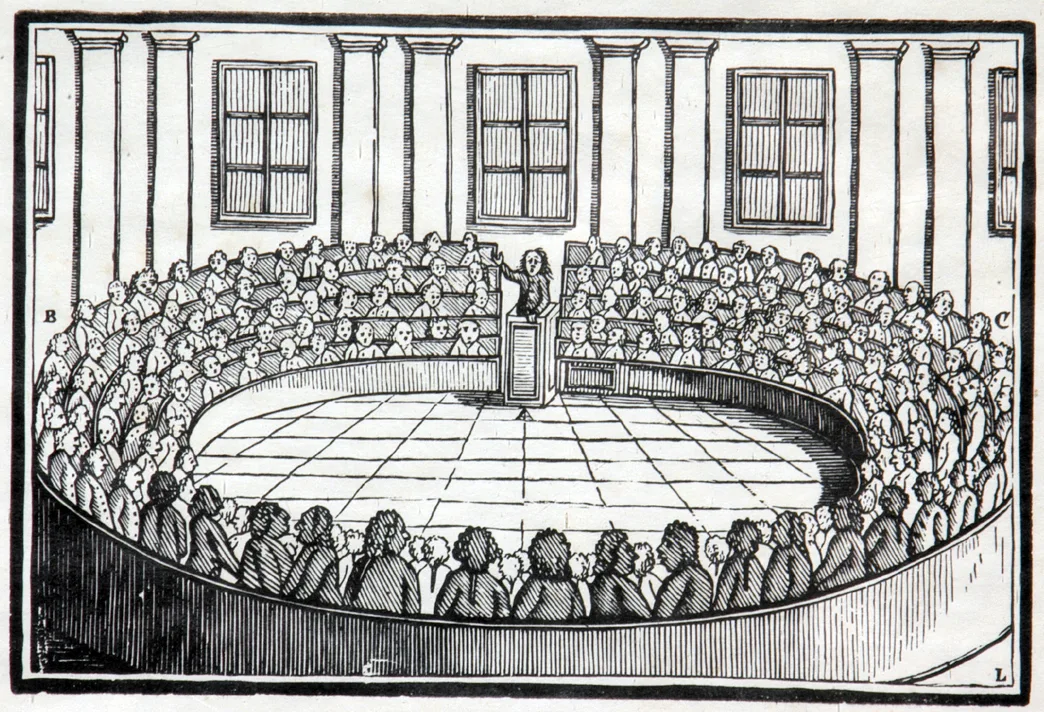

Even their contemporaries were aware that aside from the decidedly pro-revolution climate and relatively central location, there was not much going for Aarau as a capital city; the shortcoming of a complete lack of infrastructure was all too evident. The city of Aarau acted decisively and quickly to combat this deficiency. Even before the end of April a draft was drawn by Berne-based architect Johann Daniel Osterrieth, which provided for the creation of a new district in the east of the historic centre, which would double the surface area of the city. This plan entitled “Projet d’Agrandissement de la Comune d’Aarau”, or Project to Expand the Commune of Aarau, still wins the respect of city planners today for its rationality and vision. In his draft, Osterrieth valued the overall picture, not individual buildings. The design reflects the ideas of the Revolution, such as the separation of powers: Directory, Parliament and courts were to be housed in different buildings.

Draft drawn by Johann Daniel Osterrieth for the expansion of Aarau. Image: Aarau City Museum

On 3 May 1798, the Helvetic Council members confirmed Aarau as the provisional capital. A few days later, the Helvetic executive, the Directory, placed an order, so to speak, setting out the type of premises to be provided by the city of Aarau. There was, after all, an acute shortage of space in terms of both conference and residential buildings. The city placed all of its public buildings, without exception, at the disposal of the central government, and the citizens accommodated the functionaries of the Helvetic Republic.

The speed of the arrangements was impressive. Within just four weeks, the city of Aarau purchased the plots, ordered construction materials and immediately began the excavation work for those homes that were given priority – even before specific building plans had been devised. These extremely functional terraced houses, which were state-of-the-art at the time, were tackled first because of the housing shortage.

Presentation plan for Laurenzenvorstadt. Image: Aarau City Museum

In the middle of this construction euphoria, individual parliamentarians in the Helvetic Republic expressed concerns about Aarau’s suitability as the capital city. In fact, in August a majority voted in favour of relocating the capital to Lucerne. When the politicians moved south in early September, Aarau was left as a building site. Nevertheless, the residential buildings lining Laurenzenvorstadt, a street in Aarau, were still built according to Osterrieth’s plans – though this took until the 1820s. They are a stone monument to the capital city adventure.

What else has remained of this hasty experiment in democracy in Aarau? An open mind! Thanks to the authors Zschokke and Troxler, Aarau continued to influence Switzerland as a liberal centre through to the mid-19th century. A durable relic is also the canton of Aargau, which was born during the Helvetic Republic and expanded even further during the period of Mediation – with Aarau remaining (largely unchallenged) as its capital city to this day.

The “Neue Häuser”, or new houses, in Aarau are the only buildings that went beyond the planning stage for the new capital city of the Helvetic Republic. Image: Wikimedia