The great liberalisation

In the late 1960s, Swiss citizens were talking about hair length, education and voting rights for women. In a matter of just a few years, society underwent a profound change.

Swiss society in the late 1960s was at war with hair. There were strenuous attempts to keep a check on the length of men’s hair: sons and apprentices were packed off to the barber, recruits were shaven bald and rebellious ‘long-hairs’ were simply not served in restaurants and found themselves barred from dances. But all to no avail. Inch by inch, long sleek locks and silky tresses on men crept into the fashion magazines, and in the 1970s shoulder-length was perfectly acceptable – chic, even – for the man of the day.

There was no revolution in 1968 – but the year brought with it a huge transformation in western society, for which one year alone was not enough. In the 1960s, not only did the Swiss call time on the strict short-back-and-sides hairstyle for men, but quite a few other well-established practices finally fell by the wayside. The rules governing how men and women behaved with one another became freer, and education gradually moved away from corporal punishment and authoritarian discipline. Dress habits became less formal: the tie, which people such as students had still routinely worn at university until well into the 1960s, was increasingly shunned as a symbol of ‘the establishment’. People dealt with each other on a more equal footing, and the informal form of address ‘du’ came into more common usage – accepted rules of behaviour and propriety were observed less often. The books of Loriot, which had poked fun at these rules as far back as the late 1950s, show that this transformation didn’t appear out of nowhere – but it was accelerated in the late 1960s.

This advertisement from 1973 illustrates the fashion of the time very well.

Demonstration in Lausanne, early 1970s. Photo: Swiss National Museum / ASL

What was the impetus behind this change? One driver was certainly the emerging ideals of the youth movement – in demographic terms, also driven by the baby boomer generation after 1945. But the lifestyle revolution also benefited from a historic tailwind provided by the economic conditions. The country was experiencing an economic boom, and in these overheated times labour was in short supply. If you can find a new job anytime you want, you no longer have to put up with all the rubbish your boss throws at you. In 1968, a meeting was held in Switzerland at which employers aired their grievances about the ‘crisis of authority in the economy’: employees, becoming more independent as a result of the economic boom, would take any “word of criticism, any minor discussion, as an opportunity to change their job”.

At the same time, consumerism went from covering needs to self-discovery. Advertisers aimed to re-educate people to expect and demand more pleasure and greater comfort, and brushed off puritanical calls for self-restraint. In the mid-1960s, Barbie hit the market – a doll which, market researchers believed at the time, would help little girls rebel against the traditional ideas of their mothers. At the same time, the miniskirt became a symbol of female independence.

1968 stands above all for a rejection of uniformity and boredom: The revolt was directed against the ‘knock off work, television, felt slippers, bottle of beer’ attitude, in favour of more satisfaction, as on the famous poster in the Zurich summer of 1968. People wanted to reinvent themselves and leave behind outdated ideas – some on the barricades, some in the supermarkets, and some in the way they lived.

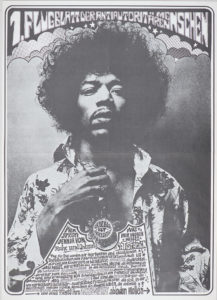

First leaflet by the "antiauthoritarian people", Zurich 1968. By Roland Gretler, Eric Bachmann, Leonard Zubler, Peter König. Photo: Swiss National Museum

Imagine 68. The Spectacle of the Revolution

National Museum Zurich

14.09.18 - 20.01.19

Following the successful exhibitions “1900–1914. Foray into Happiness” (2014) and “Dada Universal” (2016), in 2018 Stefan Zweifel and Juri Steiner present their perspective of the generation of ‘68. The collage of the two guest curators, featuring objects, videos, photos, music and works of art, turns the atmosphere of 1968 into a multisensory experience. The exhibition takes a comprehensive look at this cultural time period, letting visitors float through Warhol’s Silver Clouds into a world of fantasies past.

In February 1969, women in Zurich demonstrated for the right to vote. Photo: Swiss National Museum / ASL