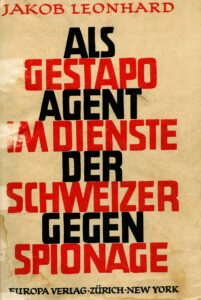

Double agent Leo

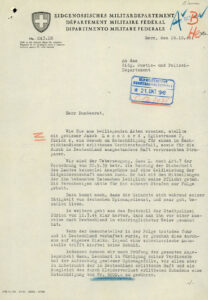

Jakob Leonhard spied for the Nazis. When they realised that the information he was feeding them had been rubber-stamped by Switzerland, his life hung by a thread.

Entry to the SS

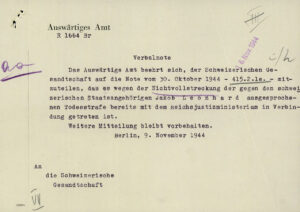

Sentenced to death by beheading

Before embarking on his ‘career’ as a double agent, Jakob Leonhard was a fraud and a trickster. He passed himself off as an anti-fascist fighter and claimed to have fought on the frontlines in the Spanish Civil War. For that he was jailed in Switzerland. Read the first part of the story here.